Laptops and calculators are sprawled across a group of four desks at Horizon High School on Madison’s west side. Bookshelves line the wall, holding titles like “Romeo and Juliet,” “Holes” and “Malala.” At the front of the room, string lights border the whiteboard.

A 17-year-old senior named Cassidy sits at a table in the back of the classroom. She’s licking a lollipop and keeping a tally of each lick on the back of a worksheet as she goes. During this science lesson, students are using the scientific method to answer the question posed in a classic commercial: How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop?

“Oh! I made it!” Cassidy says as she reaches the wad of chocolate in the middle. She and a table partner count up the tallies. It took Cassidy 203 licks.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

There are 14 students at Horizon, an alcohol- and drug-free high school designed specifically for students recovering from substance use disorders and mental health disorders. It’s Wisconsin’s only recovery high school. But after a push by advocates resulted in new state funding, that could change in coming years.

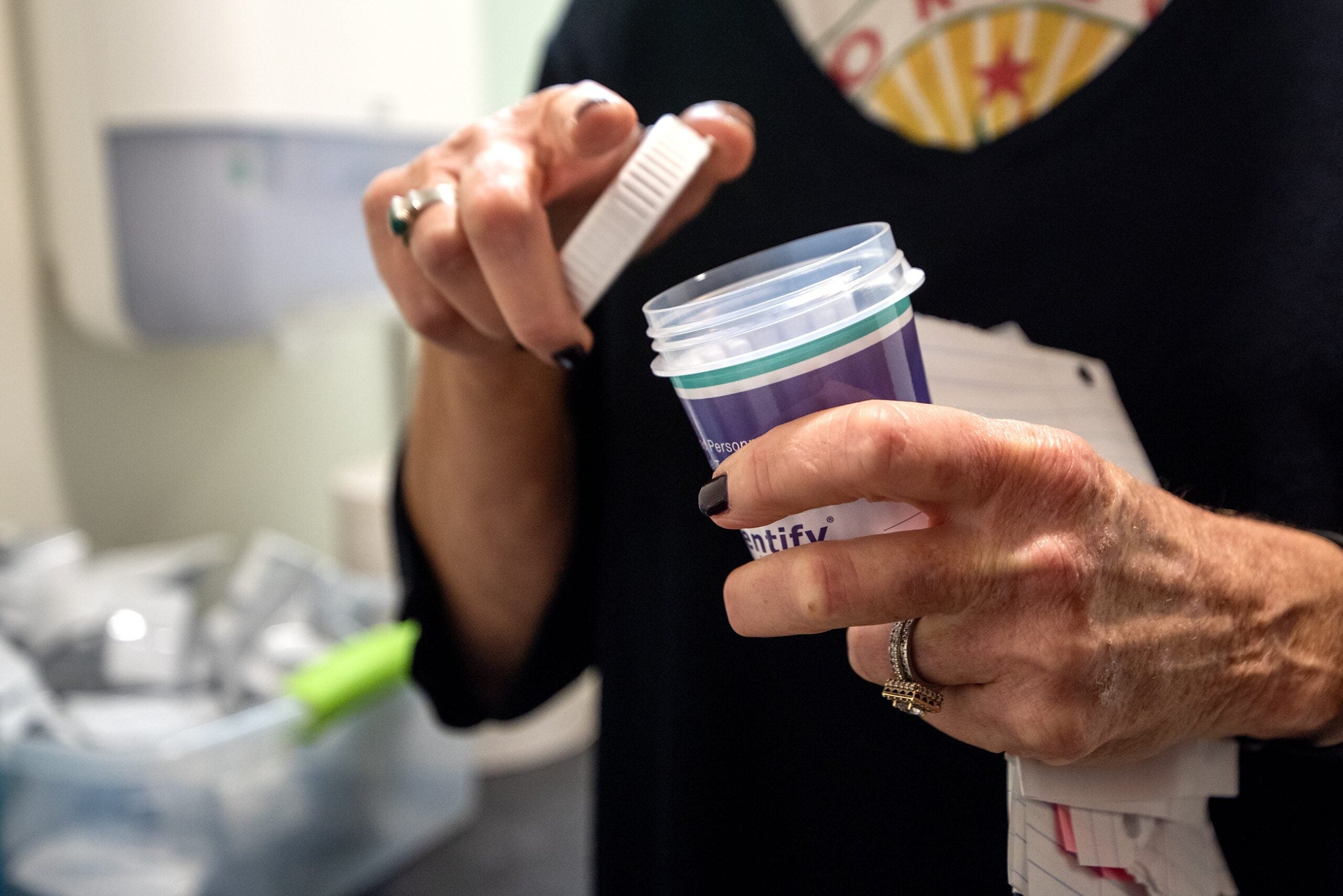

The private, nonprofit school contracts with schools in the surrounding area. It has small staff-to-student ratios, random weekly drug testing of all students, twice-weekly group therapy sessions and immediate attention to mental health crises.

School leaders say they aim to provide personalized academic and emotional support as students work toward establishing and maintaining sobriety.

Traci Goll, Horizon’s director, said there is clearly a need. Horizon serves the Madison area and has a waiting list. It can’t accommodate every student who would like to go there. Meanwhile, survey data shows that mental health struggles and substance use persist on high school campuses.

Goll said the pandemic made everything worse.

“We’ve always had kids who have been struggling with substance abuse and mental health, but I think it’s just gotten so blown out of proportion,” Goll said.

New state funding is meant to help. The 2023-25 state budget includes $500,000 in grants that may help to fund Horizon and potentially allow others to establish new recovery schools elsewhere in the state.

Students say coming to Horizon changed their lives

Horizon High School sits off a six-lane road next to a yoga studio and a pizza restaurant. Inside, there is one main classroom, smaller workrooms, a kitchen and a food pantry.

“I fell in love with it right away. I knew it was going to be the best for me,” Cassidy said. “I knew I was definitely going to be more successful than I was in my other high schools.”

WPR is not identifying Cassidy or other students at Horizon High School by their full names in order to protect their privacy.

Cassidy loves doing her nails, reading romance novels and watching TV dramas. She’s also faced social anxiety and substance use.

Cassidy smoked weed for the first time in fifth grade. By the time she started high school, she was getting high multiple times a day. She said she was an aggressive and anxious person.

She felt ignored by her teachers at her two previous public high schools. She’d skip class, and as far as she could tell, no one noticed or cared.

“I started coming here. They were telling me they care,” Cassidy said. “It’s like you’re not alone when you go to a school like this.”

Horizon, which was established in 2005, has served more than 200 students. Data from Madison Metropolitan School District shows that the 52 students who attended Horizon from 2017 through the spring of 2021 had almost perfect attendance, a dramatic drop in suspensions compared to their previous schools and a 62 percent graduation rate.

That is lower than Madison Metropolitan School District’s expected graduation rate of nearly 89 percent. But a 2017 study found that the high school graduation rate for recovery high school students is at least 20 percentage points higher than the graduation rate for similar students who have had substance use disorder treatment but did not participate in a recovery high school for a prolonged period. Sobriety high school participants also had higher rates of sobriety.

Goll said the main requirement for attending Horizon is that the student has to want to get sober. She said students go through a lot to start that journey.

“(Students need to think,) ‘I’m not where I want to be in life and I’m ready to be the best version of myself, which means I’m going to not use any kind of substances and I’m going to work really hard on my mental health,’” Goll said.

Tiah, a senior at Horizon, was ready to get sober when she was 15 years old. In a letter she wrote to Wisconsin lawmakers supporting the grants during deliberations over how the money could be used, Tiah said while she was enrolled in her public high school, she spent her days locked in her room feeling worthless.

“I lost all respect for my own life. I didn’t care if I lived or died,” she wrote in her letter of support.

In an interview with WPR, Tiah said when she started at Horizon as a sophomore, her goals were to get sober and improve her relationship with her mom. Now, Tiah said they are best friends and talk all the time. She said she no longer uses drugs, and she uses the skills she learned at Horizon to keep her life on track.

Horizon has seen expenses rise while donations have stagnated

Clinical substance abuse counselor and therapist Madeline Brown leads the school’s group therapy sessions and meets with students individually. She said being surrounded by people who share the goal of sobriety is critical for success. Returning to a traditional high school after inpatient treatment, she said, can derail progress.

“If you go back into an environment that’s not constantly supporting sobriety, it’s going to be really difficult,” she said.

According to the 2021 Wisconsin Youth Risk Behavior Survey — a biennial survey of teens that’s meant to capture trends in drug use, mental health and physical health — 26 percent of high school students currently drink alcohol. That number has been in continuous decline since 2007. Fourteen percent currently use marijuana, a decade-long downward trend, and 10 percent have been offered, sold or given illegal drugs or alcohol on school property. Even as fewer young people say they are using drugs and alcohol, that leaves a sizable number of students who are using them — including some with serious addictions.

More than half of the students surveyed were anxious and a third were depressed. Rates were highest among students who identify as LGBT, food insecure, Hispanic and students with low grades. Data shows increasing levels of depression and self-harm for at least a decade.

Horizon is funded mostly through private donations and grants. According to John Fournelle, the president of the school’s board of directors, the school’s expenses went up 36 percent between 2021 and 2022 and donations haven’t increased. The school is on track to have about $40,000 in debt this year.

Goll said new state funding has the potential to help Horizon weather challenging finances.

“Everything we do costs money,” Goll said. “How are we going to keep the doors open on Horizon and give the kids what they deserve and need?”

On Wednesday, Gov. Tony Evers signed a bill that details how the grant money can be used. Horizon is eligible for some of the grant money, but a majority of the money will go to other sites to cover planning and startup costs for new recovery schools in Wisconsin.

The Association of Recovery Schools, a national organization based in Pennsylvania, offers technical support to communities trying to build recovery schools. Roger Oser, chair of the association, said recovery schools save individuals and families and help society at large by keeping many students from “dropping out of school, becoming court-involved, a medical cost to society, or God forbid, obviously with opioid-based addictions, higher mortality rates and overdoses.”

As of 2019, the estimated economic cost of substance abuse disorder in the United States is approximately $3.73 trillion annually, according to a study from the Recovery Centers of America.

There are 45 known recovery schools throughout the country. According to Fournelle, a decade ago, two other charter recovery schools in Wisconsin closed due to local school district budget cuts.

Brown said recovery schools help students in ways other schools and programs can’t.

“We’ve made relationships together, so they know me, so they’re going to be more likely to reach out if they’re struggling. And that’s definitely going to happen when someone’s staying sober,” Brown said.

There is potential for more recovery schools and the students they serve

Tiah hopes state funding will bring more opportunities for kids like her.

“Horizon has taught me so many things, from how to be confident in my education to how to be a contributing member to society,” she wrote in her letter to the Senate Committee on Mental Health, Substance Abuse Prevention, Children and Families and the Assembly Committee on Education.

Goll said she’s heard rumblings of other recovery schools possibly opening in other Wisconsin cities. She says no one is going to take a leap of faith without guaranteed funding.

But Goll said recovery schools are worth the financial investment.

“It’s pretty magical to watch a teenager walk through our doors and just be a huge, hot mess. I mean, failing in all areas of life,” Goll said. “And they get sober and all of a sudden, things fall into place.”

On Cassidy’s self-declared “bring-your-squirrel-to-school day,” she slid the cage open and the pet, named Azie, scampered out, scaling Cassidy’s shoulders before stopping to snack on nuts and seeds in her outstretched hand. At around the same time she started at Horizon, Cassidy found the baby squirrel with a bloody nose at the base of a tree in a park near her house. Cassidy took her home and cared for her. She said she feels like Horizon has done the same for her.

Cassidy recently earned all A’s, something she said hasn’t happened since middle school. Now she has a job, dreams of going to cosmetology school and feels more confident in her social skills.

In her own letter to lawmakers, Cassidy said Horizon saved her life.

“They made me love myself again, love going to school and doing work, the three things I never would’ve thought I was going to say again, but everyone there changed that,” Cassidy wrote.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.