On October 18, 1967, a protest at the University of Wisconsin-Madison turned into a riot, and the city became a focal point in the fight at home over the Vietnam War. Our guests reflect on the events of what came to be known as “Dow Day,” when students who opposed Dow Chemical Company’s recruitment on campus clashed with Madison police. More than 70 people were injured, and the the violent confrontation — and the university administration decisions that led to it — energized the anti-war movement at UW Madison and beyond.

Were you a student at the UW during that era? What do you remember about the Dow protests? You can send an email to ideas@wpr.org, post on the Ideas Network Facebook page, or tweet us @wprmornings.

Featured in this Show

-

Remembering The Dow Protest And Riot 50 Years Later

The 1967 University of Wisconsin-Madison Dow Chemical protest isn’t just another story of Vietnam-era campus activism.

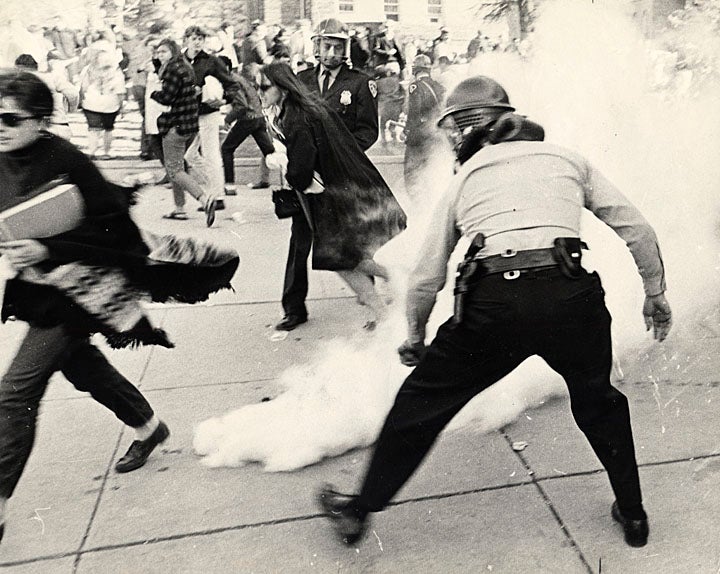

It was the first time things really turned violent at a peaceful campus protest because of a police riot, said David Maraniss. There were billy clubs, tear gas and hospitalizations. The protest and riot radicalized formerly indifferent students, engendered years of protest at UW-Madison and made national news.

Maraniss is an editor at The Washington Post and the author of “They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace Vietnam and America October 1967.” The book juxtaposes a Viet Cong ambush against an American battalion on Oct. 17, 1967 with the Dow protests in Madison. His book has been adapted into the Emmy- and Peabody-award winning documentary “Two Days In October.”

“I was a freshman on the campus that fall, wearing my first blue jean jacket and experiencing tear gas for the first time. It stuck with me in a very powerful way, so that 35 years later I would write about that event as a way of trying to capture the Vietnam War,” Maraniss told WPR’s “The Morning Show.”

The protest, which happened 50 years ago this week, was organized by student leaders of the anti-war movement who noticed that Dow Chemical would be coming to campus to recruit students.

Dow had become a symbol of the war because it manufactured the chemical warfare agents napalm and Agent Orange. At the time, the horrific effects of napalm were known to the American public because it was “shown on television burning villages and maiming people,” Maraniss said.

Dow protesters gathered in the Peterson Building at the UW-Madison. Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison ArchivesStudents organized a sit-in at the Commerce Building (now Ingraham Hall) where Dow planned to hold interviews. There were hundreds of protesters, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in an attempt to prevent the interviews from taking place. The protesters were mostly successful; a few interviews happened, but the rest were cancelled, Maraniss said.

The university demanded protesters leave, but they refused. Chancellor William Sewell called the Madison police — a decision he would come to regret.

Sewell was anti-war, but he hadn’t experienced this type of protest.

“That night he went home and realized that this is what he would be remembered for for the rest of his life, no matter what he did,” Maraniss said.

The peaceful protests spiraled into violence when police fired teargas into the crowd outside the Commerce Building, hitting students in the legs, heads and stomachs. Ultimately, nearly 70 people, including 19 police officers, were hospitalized.

For many students who’d been indifferent to or in favor of the Vietnam War the riot politicized them. Those who had been anti-war but not politically active, became radicalized.

Prior to the protest, the anti-war movement at UW-Madison had been “deep but not wide,” Maraniss said, citing only a few hundred students who were actively participating in the movement.

After Oct. 18, the anti-war movement on campus expanded into “more than just a few hundred committed, knowledgeable anti-war leaders. Everything changed with Dow,” he said.

Vicki Gabriner, a guerilla theater mime at the Dow riots, in the back of a paddy wagon guarded by a police officer in riot gear. Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison ArchivesIn the fall of 1967, Bob Grueneberg was a sophomore transfer student at UW-Madison. He was wheeling his bicycle between classes when he stopped to watch the protest.

“At the precise moment when the police basically charged into the crowd, and then subsequently launched tear gas canisters, one of which landed literally in the spokes of my bicycle,” Grueneberg told “The Morning Show.”

“I was certainly aware of the war, and against it, (but) I was not actively involved. I was angry that suddenly I was assumed or made part of the protest. Why were people who, I think a lot of whom were just observing, being attacked by the police?” he asked.

After that experience, Grueneberg became politically active, attending campus protests for the rest of his time at UW-Madison.

And there were many to attend.

After Dow, “There was a protest every semester. There was a T.A. (teachers assistant) strike, there was a strike against a bus lane, there was a black student studies strike. It was one protest after another,” Maraniss said.

Widespread protest and student outrage at what they saw as the administration’s complicity with the war was in large part engendered by the Dow protest and police riot.

“The ’60s really sort of started to begin after Dow,” he said.

Hear “The Morning Show” Callers Talk About The Protest:

Episode Credits

- Kate Archer Kent Host

- Michelle Johnson Producer

- David Maraniss Guest

- Bob Grueneberg Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.