Wisconsin schools received $2.4 billion in federal relief aid over the past two years, and so far, that money has largely gone toward educational technology, responses to COVID-19 and addressing the effects of school closures, according to a new report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

Schools have received three rounds of federal funding in the form of Elementary and Secondary School Education Relief, or ESSER, funds, which went to every school district, and one round of Governor’s Emergency Education Relief, or GEER, funds, which went to fewer than half of the state’s districts.

The majority of the state’s ESSER money was allocated based on student income, with more money going to schools with more low-income students. GEER funds were doled out via a formula based on economic disadvantage, access to technology and test scores.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Report author Sara Shaw found that the three categories — technology, COVID-19 preparation and response and responding to school closures — have held steady throughout schools’ relief spending so far, but they’ve shifted a little bit from tech-heavy in the first round to more closure-oriented in later rounds.

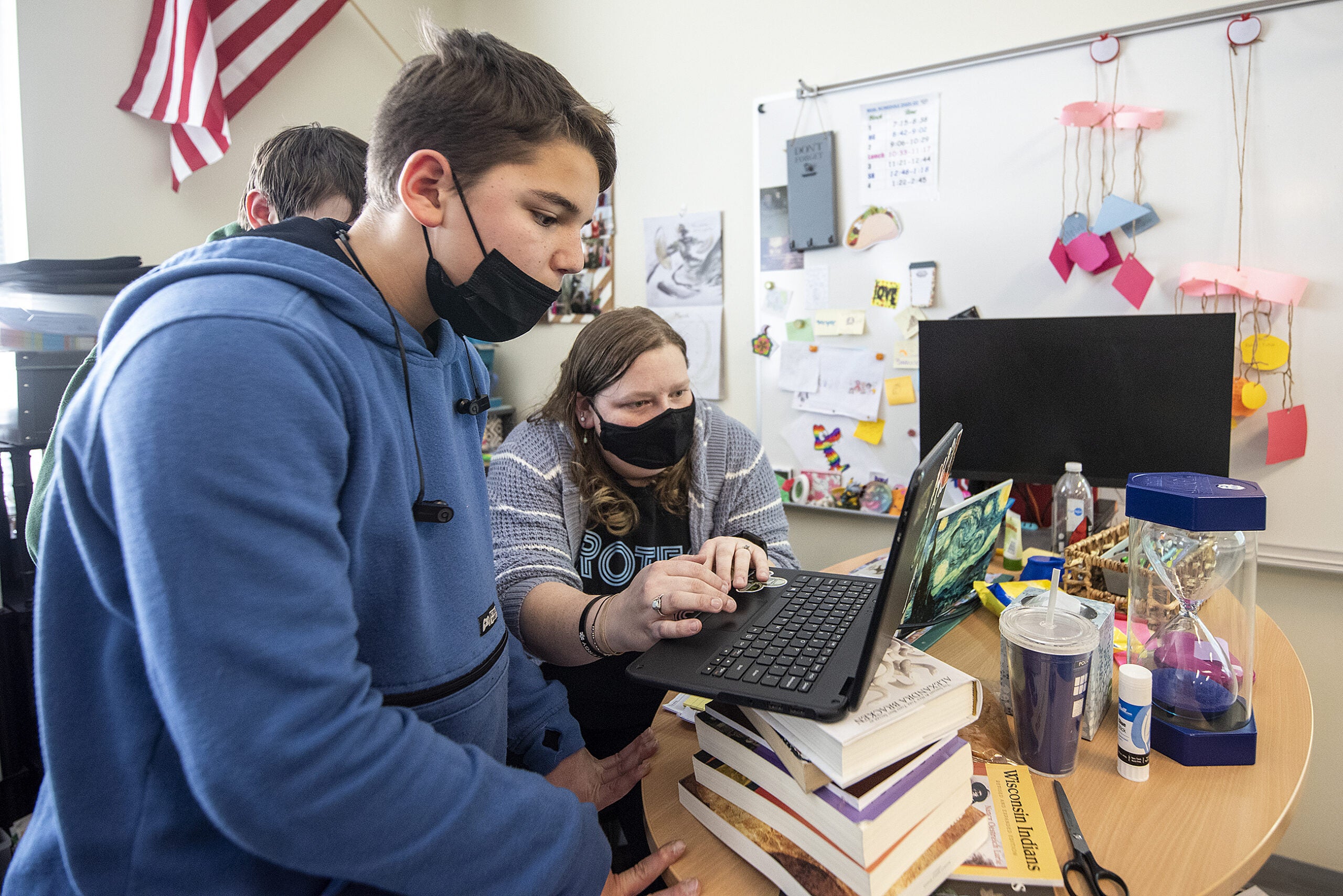

With the first round of funds, schools covered a lot of emergency pandemic needs. They bought child-sized masks, hand sanitizer and air filters; ordered hotspots and laptops for students learning at home; and purchased curricula and related staff training for at-home learners.

“That seemed to make some intuitive sense, that in that first wave of panic, reacting to COVID, was about how do we get our kids connected, how do we get our staff connected, how do we get our district connected?” Shaw said. “Now, spending on addressing long-term school closure is rising, and (officials with the state Department of Public Instruction) told me that they do expect that trend to continue over both the rest of ESSER II and into ESSER III, as school districts are investing in how to adapt.”

Subsequent rounds have let districts look at bigger or more long-term projects, like updating their schools’ ventilation systems, mental health services and buying new curriculums that might work better for students who might have missed key concepts during COVID-19 disruptions.

The money is also time-limited. Districts need to spend the last round of funding by the end of 2024, and the earlier rounds before that.

“These are one-time funds,” Shaw said. “Any time a district is considering that the funds be used to cover normal operational costs, that should raise eyebrows, because that means you’re now building into your budget a recurring cost for which you do not have a recurring source of funds.”

Differences between districts

The report found that schools in different areas have, in some ways, spent their relief funds differently.

Educational technology spending was highest in urban and suburban districts, while districts in towns and rural areas put more of their funds into COVID-19 preparedness and response.

“(Rural districts) were by and large returning to all in-person learning faster than our urban district, so they may have more quickly shifted from education technology over to preparedness and response to COVID,” Shaw said. “It may also have meant that there were certain things that the ESSER funds couldn’t touch — if you’re facing broadband challenges, that’s not a district-specific problem, that’s a regional issue.”

Shaw saw the same patterns emerging based on student population and wealth. More populous and lower-income districts spent more heavily on technology. Less populated and higher-income districts spent more on COVID-19 preparedness.

Challenges with one-time funds

Although staff costs — salaries, benefits and overtime — are generally schools’ largest expense, school leaders have shied away from using federal relief funds to pay teachers and support staff because they’ll be on the hook to keep those positions funded out of their own budget after federal dollars run out. Still, Shaw said schools have found other, creative ways to invest in their staff without setting themselves up for a fiscal cliff.

Some, she said, have used money to re-train existing staff for different roles within the school. Others have partnered with nonprofits and companies to bring in counseling services, tutors or other people who can help students recover from the pandemic in time-limited roles.

Schools are facing other financial pressures, though. The most recent state budget did not increase the amount of money schools receive, even as the same inflation costs hitting grocery budgets and gas prices are making their everyday costs balloon.

“They have this federal largesse that comes with an expiration date, and they have their normal operational costs, and if inflation were only touching their COVID costs, that might be fine, they have the money right now to handle that,” Shaw said. “The trouble is that inflation doesn’t discriminate between those one-time costs and recurring costs.”

In addition, inflation means higher cost-of-living adjustments for staff, which is one of those recurring costs that districts don’t want to use one-time funds for.

“School districts, out of a desire to retain staff, especially amid concerns about burnout and a tight labor market, are really contending with how much should they be building into upcoming budgets for staff cost-of-living adjustments,” Shaw said. “A lot of district leaders I’ve spoken to feel really caught between what they feel like they need to do to retain staff, what they feel like they need to do to address student needs right now, and what they need to do to be fiscally responsible.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.