The share of Wisconsin high school students deemed to be college-ready has declined since the 2014-2015 school year according to a new report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum. While the state leads most others that test 100 percent of high school students, the data also shows significant gaps in college-readiness based on race and economic status.

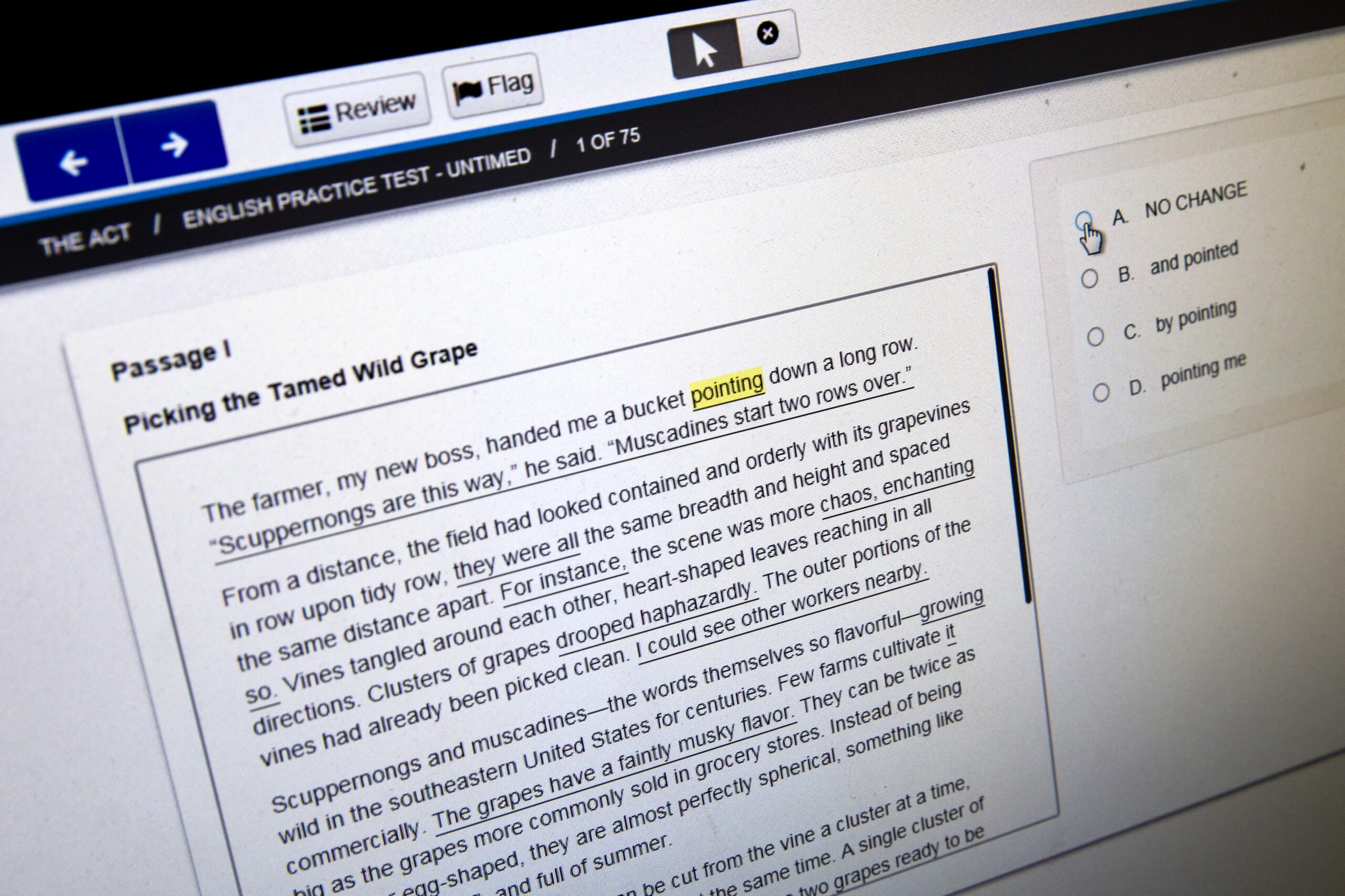

The Wisconsin Policy Forum analyzed ACT data collected by the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) since it began requiring all high school juniors to take the ACT.

The report shows that the state’s composite score — an average of all results — fell slightly last school year to 19.6 compared to the average of 19.8 from the 2017-2018 academic year. The state’s composite ACT score during the 2014-2015 school year was 20. Those numbers are important because ACT scores are one of the factors colleges use when deciding which students to admit. For the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire an ACT composite score of 21-26 is recommended students. For UW-Madison an ACT score of 27-32 is recommended.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The Policy Forum notes, however, that the slight decline in the state’s composite score “is masking potentially significant declines within each subject area that are relevant to students’ ‘college readiness.’”

The ACT sets benchmarks to determine a student’s ability to earn passing grades in English, math, reading and science. In each subject, less than 50 percent of students met the goal. The state’s benchmark scores for reading increased slightly during the last school year over numbers from 2017-2018.

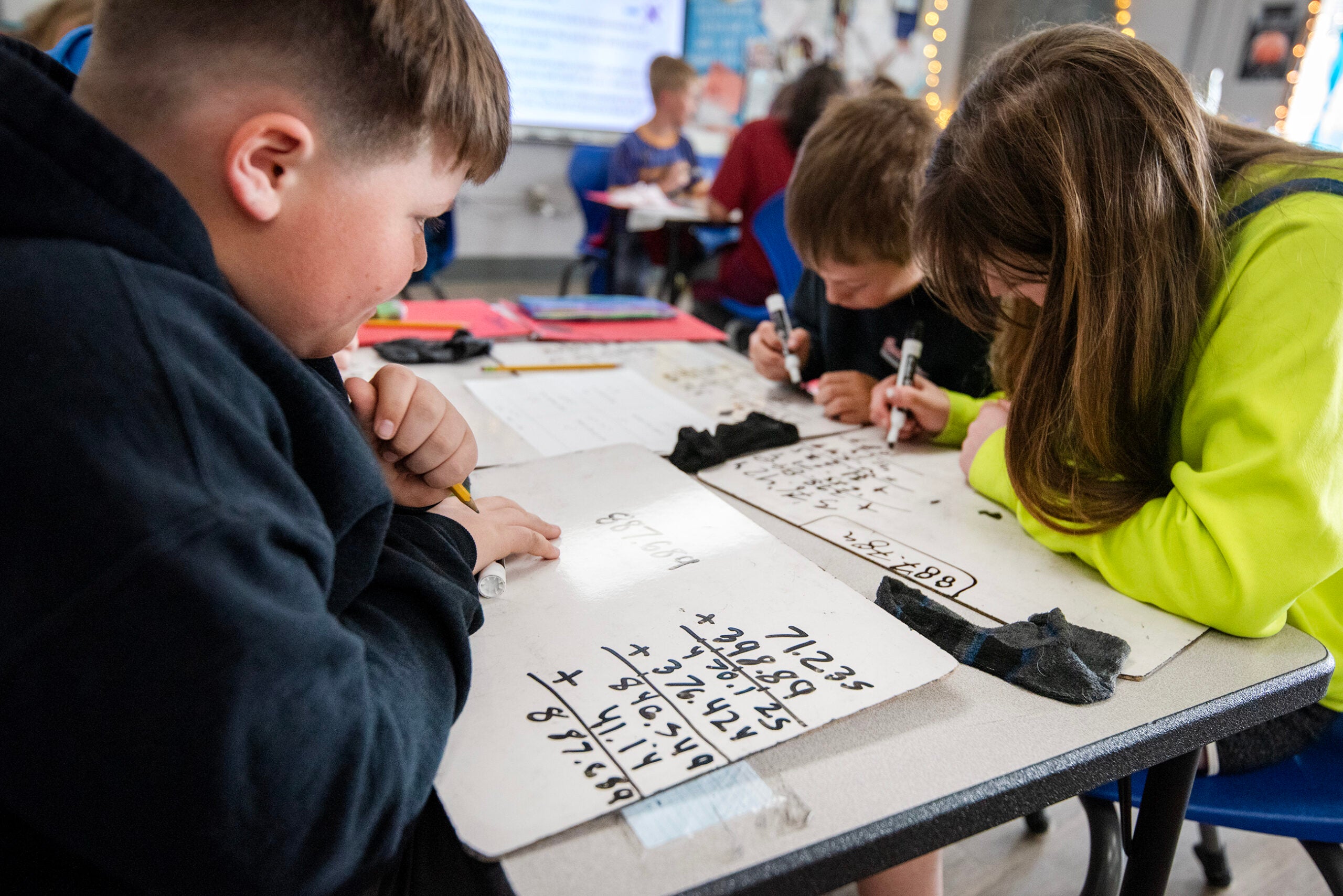

The subject students struggled most with was math. Only 29.2 percent of all Wisconsin students met the ACT math benchmark. But when broken down by race the report noted that only 3.9 percent of black students met the college readiness benchmark for math while 35 percent of white students met the requirements.

The largest gap between black and white students were noted in ACT reading scores. While 42 percent of white students met the reading benchmark, only 8.7 percent of black students achieved the same results.

In October, data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress results, which samples standardized test scores from a sample of fourth and eighth grade students, showed Wisconsin had the widest educational achievement gap in the nation.

DPI Senior Policy Advisor Jennifer Kammerud told WPR the data isn’t surprising because the state has historically had some of the widest achievement gaps in the United States.

“Too many of our students of color, students with disabilities, English-learners and students from low-income families continue to struggle to reach their full potential,” said Kammerud. “And we know that the education system as a result of these results isn’t working for everyone at all times and we need to do more to ensure our schools have what they need to ensure the success of all students.”

Kammerud said there’s no one solution to reducing the achievement gap or increase students’ composite scores. But she pointed to efforts including the implementation of The College and Career Readiness Early Warning System and the Dropout Early Warning System, which are data tools that make predictions about whether students in grades six through nine are likely to be ready for college or a career or if they’re in danger of dropping out.

Kammerud also said the state’s five largest urban school districts — Green Bay Public Schools, Kenosha Unified School District, Milwaukee Public Schools, Madison Metropolitan School District and Racine Unified School District — have partnered on an effort called the Wisconsin Urban Leadership Institute aimed at providing strategies for making public education more equitable for students of color.

When asked why the state’s overall composite ACT scores have dropped, Kammerud said poverty levels have increased and more students are arriving to school with additional needs. She also said caps on school district spending that have been in place since the early 1990’s and low state reimbursement rates for local special education.

“And that matters because when a district has to provide those services that means they’re taking money from somewhere else because they are under revenue limits, which limit the amount of money they can spend,” said Kammerud.

She said diverting funds may make it difficult for districts to afford professional development for teachers aimed at addressing increased needs of students.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.