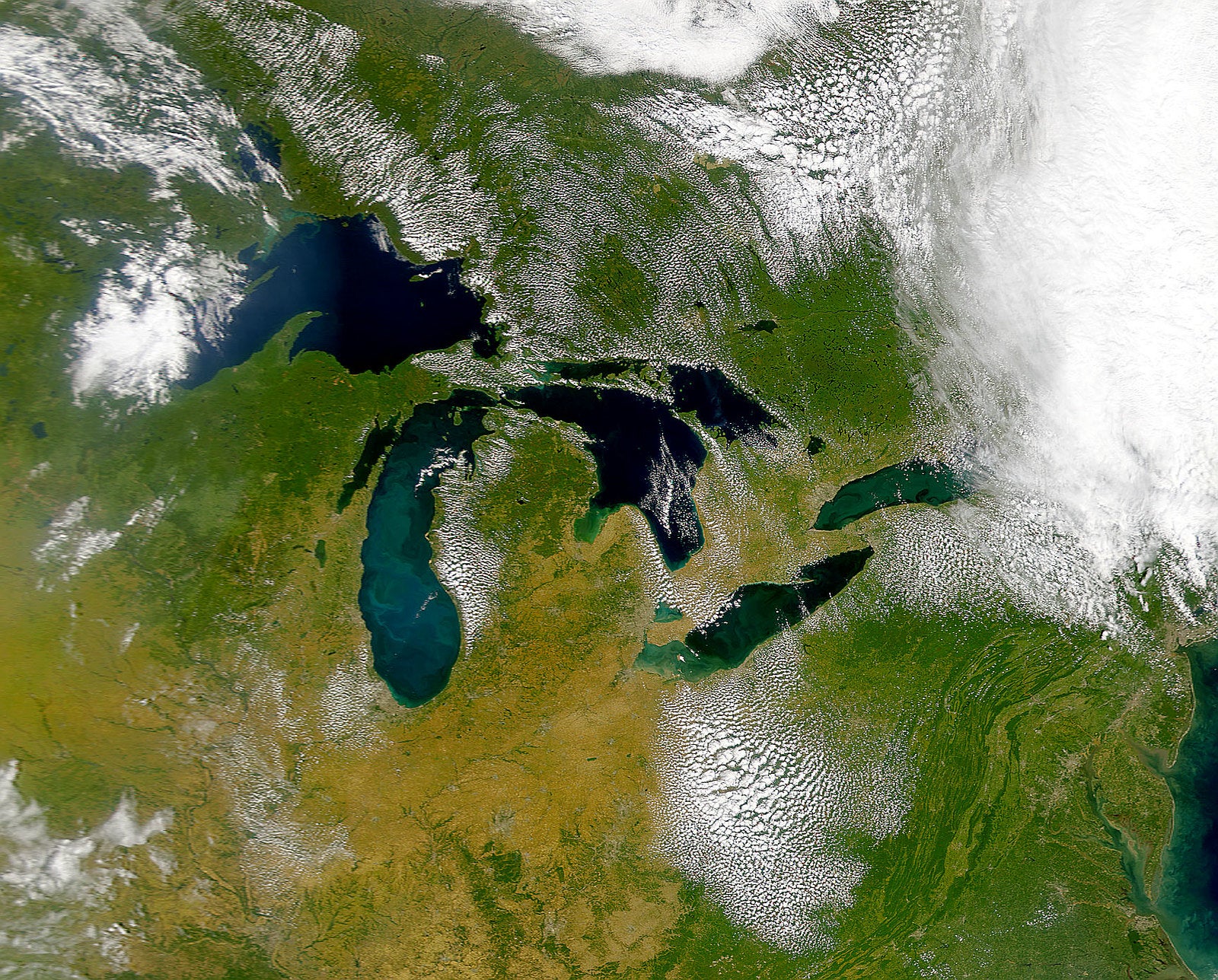

New research suggests warmer water in Lake Michigan could mean more bird deaths along the shoreline. The study by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and U.S. Geological Survey found warmer water could favor the growth of algae with toxins that are killing off birds.

The three-year study which focused on northern Lake Michigan sought to explain botulism outbreaks that have been the cause of mass bird deaths since the 1960s. Botulism leads to paralysis in animals and often causes Lake Michigan’s double-crested cormorants, ring-billed gulls and loons to drown.

Scientists used satellite data to track water temperature and measure algae in Lake Michigan, relying heavily on volunteers to collect bird carcasses. The study was conducted from 2010-13, and the research was published last week.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Jenny Chipault is a wildlife disease data specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center in Madison. She helped train the citizens who aren’t required to have scientific backgrounds in order to collect data.

“We’re asking them to identify bird carcasses by species,” Chipault said. “We’re also asking them to bury or collect bird carcasses, and so, they need appropriate training because we don’t know what these birds died from.”

Although there have been similar studies looking into what has caused botulism outbreaks, Chipault said the additional people in the field was crucial in narrowing down where the deadly toxins come from.

“This time we had enough data that we could dig in a little bit more and we could look within one year,” Chipault said. “What sort of pattern are we seeing, what species are affected when, how does that correlate with water temperatures?”

According to Chipault, the data collected by these citizen scientists is laying the groundwork for future research. That includes looking into ways of removing toxins from parts of the lake or keeping birds away from those areas.

That could be important as avian botulism is not unique to Lake Michigan. Researchers total the amount of birds killed by botulism in the Great Lakes to the tens of thousands over the past 50 years.

Outbreaks have become more common since the 1990s, scientists say.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.