More people are being locked up in Wisconsin, and the increase in inmates in county jails and state prisons is costing taxpayers and straining capacity of corrections facilities in some places.

After falling for five years, the number of people incarcerated in Wisconsin started to rise in 2015. A new WPR analysis of state data shows increases since 2015 in both the number of inmates and the percentage of jail capacity that’s being used throughout the state.

That rise has consequences.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

It puts strain on overcrowded county jails and overstretched county budgets. Jail administrators in places at or near capacity can be forced to house high-risk inmates in lower-security areas. Some policymakers at the local level have instituted incarceration-alternatives ranging from drug courts to electronic monitoring, but most efforts to institute criminal justice reform in state policy have stalled.

The trends identified by WPR are based on jail population data from 2010 through June 2019, the most recent state data available. WPR obtained the numbers through open records requests of the state Department of Corrections.

In 2010, Wisconsin’s county jails incarcerated an average of 13,600 people each month. By 2015, that number had dropped to 12,300. That was followed by three years of increases — 12,700 inmates in 2016; 13,100 in 2017; and 13,400 in 2018. Partial data from 2019 show a decline in jail populations in the first half of last year — but population levels remained well above 2015’s low-population marks.

“We’ve had quite a few challenges in the last two to three years,” said Paul Brinkman, the corrections administrator in Sheboygan County. “We’re forced to make decisions about inmate housing and place them in parts of the building that normally wouldn’t be designed for that classification of inmate.”

It’s not clear what caused the declines in inmate populations in the first half of the 2010s, but most experts attribute the rise that followed to the opiate epidemic and a more recent surge in methamphetamine use.

Wisconsin State Crime Lab data show a jump in heroin cases from about 650 in 2012 to more than 1,000 in 2013, and a rise to a high of nearly 1,350 cases statewide in 2017. Meth cases jumped from about 1,150 in 2016 to nearly 1,700 in 2017. Then meth cases fell to about 1,450 in 2018.

Sheboygan County Sheriff Cory Roeseler said the county saw signs it was outgrowing its detention facility in 2009. Then years of declines took some pressure off Sheboygan County. In recent years, that pressure has returned.

Sheboygan County hovered around 60 to 70 percent capacity in its corrections facilities. But in 2018, on average, the county was at 102 percent capacity, according to WPR’s analysis. Between two detention facilities, Sheboygan County has capacity to hold 402 inmates at a time, Roeseler said. That population fluctuates significantly. Roeseler and Brinkman said the facilities are likeliest to hit or exceed capacity during the summer and on weekends.

Roeseler said he doesn’t think crowding is so acute as to compromise safety in the jail. But he acknowledges it can force difficult decisions.

“Right now if we’re overcrowded, where are we going to put anybody that’s on an additional 12-hour hold?” Roeseler said, referring to the order that a judge can make if an offender is found to have violated probation.

In some places where jail crowding is acute, that’s made it more likely that the counties have to pay to house inmates in other jails. In 2015, the statewide average was 422 inmates per month housed outside of their home counties. By 2018, the average number was 506. That costs counties money in boarding costs and time in transportation.

The fiscal impact of rising incarceration numbers is one reason the issue has at times attracted coalitions of liberal and conservative politicians. Advocates for criminal justice reform include interest groups as disparate as the Charles Koch Institute and the American Civil Liberties Union. They point to research showing those held in jails and prisons are more likely to reoffend than those who complete alternative programs such as drug courts. In Wisconsin, Republican U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson has championed his own Joseph Project, which aims to help those who have been incarcerated to find jobs and re-enter society.

But when it comes to state criminal justice policy, there is little sign of political agreement among Wisconsin policymakers. Without a change of course, the state may see a continuing long-term trend toward more and more expensive incarceration.

Opiates, Other Drugs Account For Share Of Inmate Increases

There are many reasons for the increase in Wisconsin’s incarcerated population, but the state’s drug epidemic is one of the major ones. Jails across the state have become used to dealing with people who are facing withdrawals from opiates, or the lingering effects of methamphetamines.

Oneida County Sheriff Grady Hartman said it’s become the norm.

“Four or five years ago, I never thought our community up here in the Northwoods would have a lot of methamphetamine or heroin use,” Hartman said. “I never thought we would have overdose deaths.”

But all those things came to Oneida County.

On a recent tour of the jail, a man who had just been booked there was in restraints as he came down from drugs he’d been using when he was arrested. The tour didn’t pass directly by where the man was being held, but several times he could be heard shouting.

All jails have to respond to inmates’ health and medical needs. Dealing with the effects of substance abuse is one of the biggest tasks in jail intake procedures throughout the state. And it’s not just illegal substances that pose a risk.

“We have a couple people in there right now going through DTs really bad,” said Mark Neuman, the Oneida County jail administrator, referring to delirium tremens, an effect of alcohol withdrawal. Symptoms can include shaking, confusion and even hallucinations. “Actually one guy is in the hospital. When he comes back, we’ll have to have certain things we’ll have to do for him, give him certain kinds of liquids and things to try to bring him back.”

While Other Midwestern States’ Prison Populations Declined, Wisconsin’s Increased

Every week, members of the Oneida County Sheriff’s Office make the four-hour round-trip drive to Stanley to exchange inmates with the state. The Stanley Correctional Institution houses about 1,600 state prisoners. It’s in central Wisconsin, about an hour south and an hour west of Northwoods Rhinelander, where the Oneida County Sheriff’s Office is situated.

Oneida County has seen the same population trends in its jail as other parts of Wisconsin, but it’s unusual in that its correctional facility has more capacity than the Northwoods county requires. It contracts with the state to take about 100 prisoners at a time. The Oneida County Jail has capacity for 203 inmates, and even with increases in local inmates in recent years it averages in the high 90s, Hartman said.

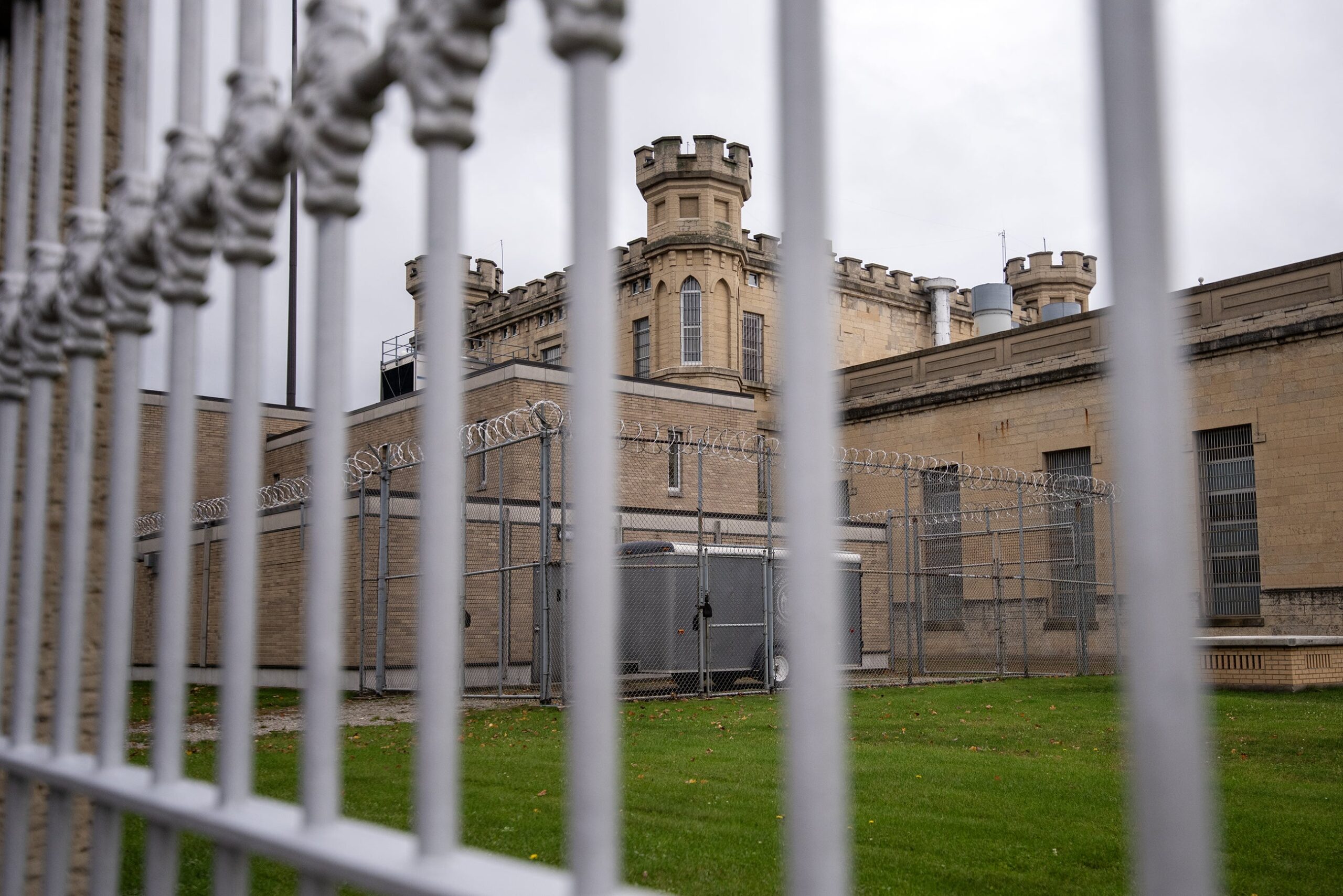

[[{“fid”:”1126886″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EOneida%20County%20Law%20Enforcement%20Center.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3ERob%20Mentzer%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Oneida County Jail”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Oneida County Jail”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EOneida%20County%20Law%20Enforcement%20Center.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3ERob%20Mentzer%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Oneida County Jail”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Oneida County Jail”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Oneida County Jail”,”title”:”Oneida County Jail”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

County jails hold people who were arrested locally, are awaiting court hearings or who have received jail sentences of a year or less. State prisons are for those with longer sentences.

A 2019 analysis of state prison populations by the Legislative Audit Bureau showed the state’s adult prison inmate population increased by 7.9 percent between 2011 and 2018, from nearly 22,000 people to about 23,600.

“When compared with six other Midwestern states,” the report’s authors wrote, “only Wisconsin experienced an increase in its inmate population from 2009 to 2018.”

Rising populations also mean rising costs. The same report found the operating costs of the state’s adult prison system increased from $909 million in the 2013-14 fiscal year to $934 million in 2017-18.

The increase in those incarcerated in prisons also leads to increased costs to the state as they make arrangements with counties, such as Oneida, to ease crowding by housing some state inmates. It’s a cost to the state, but in some ways it’s a windfall to Oneida County. The arrangement is worth about $1.2 million per year to Oneida County. The county does assume transportation, housing and health care costs for inmates. It puts the rest into its capital budget.

Gov. Tony Evers campaigned on a promise to cut the state’s prison population in half. That was always likely to be a difficult goal to reach, and there are few signs of significant structural changes in the governor’s first year in office.

[[{“fid”:”1126911″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3ERep.%20David%20Crowley%2C%20D-Milwaukee%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”David Crowley”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”David Crowley”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3ERep.%20David%20Crowley%2C%20D-Milwaukee%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”David Crowley”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”David Crowley”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”David Crowley”,”title”:”David Crowley”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]Rep. David Crowley, D-Milwaukee, is one of a group of legislators who have focused on criminal justice reforms that aim to reverse increasing incarceration. He’s introduced a bill that would limit the use of bail jumping charges, which are used to incarcerate someone who’s violated a court order, for example drinking alcohol if a judge has ordered them not to as their case proceeds through the court system. In 2018, more than 8,000 cases involving felony bail jumping charges were filed in Wisconsin, making it one of the most common felony charges deliberated in courtrooms.

Crowley said even in cases where the original charges are dropped, bail jumping charges can remain.

“You may even be found not guilty,” Crowley said. “But because you were guilty of bail jumping, now you’re doing even more time than your original charge.”

Crowley’s proposal, which would still allow for penalties for offenders who don’t show up in court, has bipartisan support in the Legislature. It’s not clear that will be enough to get it a vote, however. The two parties appear to be far apart when it comes to criminal justice goals.

In an interview in early January with the Wisconsin State Journal, Evers outlined a package of legislation from Democratic lawmakers he characterized as a “first step” toward his goal of halving the state’s prison population. The day after that interview published, a group of Republican legislators announced a press conference for a set of bills that would in part increase penalties for domestic violence. The legislators call them their “new Tougher on Crime initiatives.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.