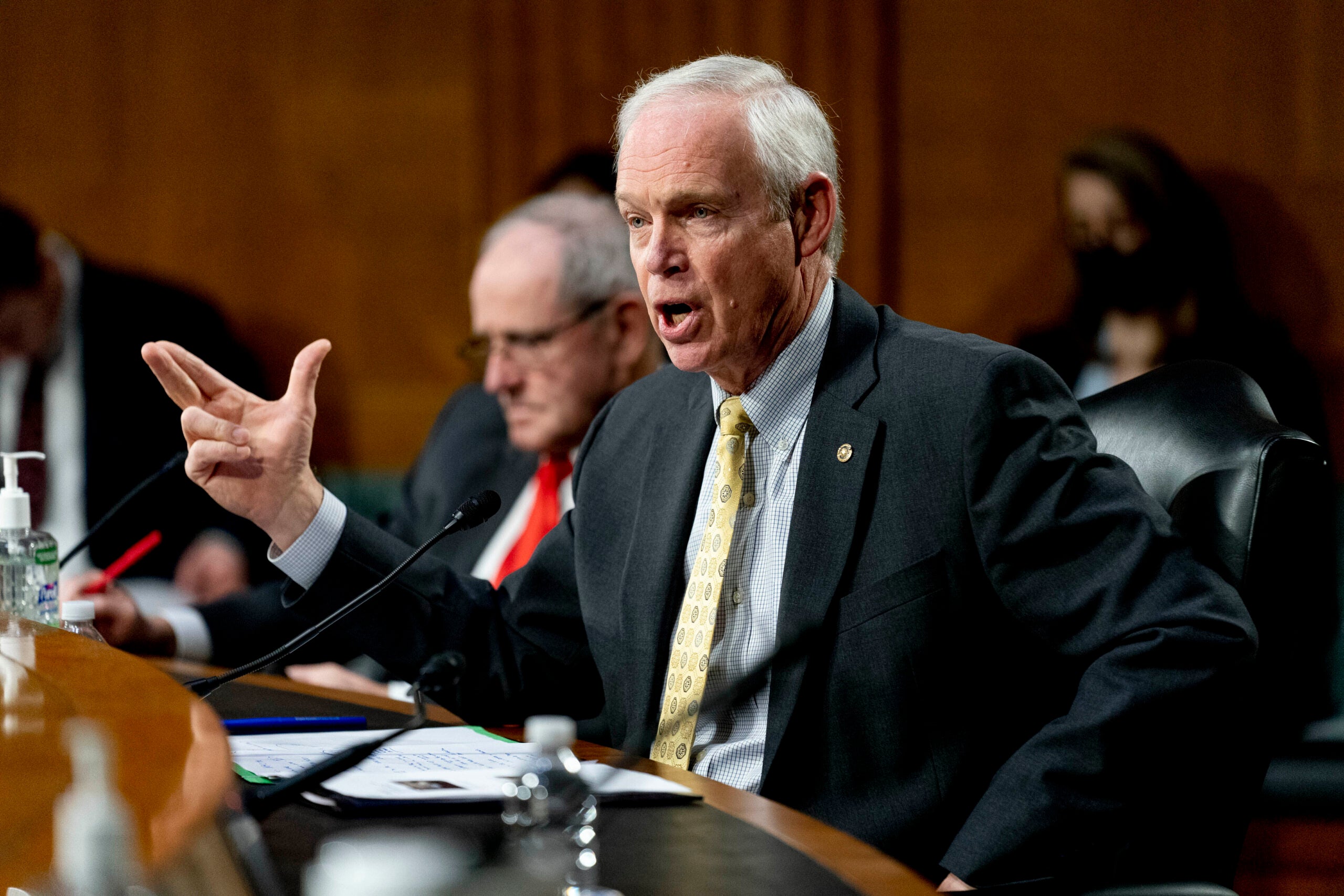

In the last two months, U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson has attracted headlines and liberal criticism for saying taking care of children isn’t “society’s responsibility“; for declining to call on Oshkosh Defense to manufacture next-generation mail trucks in Wisconsin; for raising the possibility of an Affordable Care Act repeal in the next Congress; and for calling a GOP proposal that would cut Social Security and raise taxes on seniors “a positive thing.”

The Oshkosh Republican, whose 2022 reelection campaign is among the nation’s most closely watched Senate contests, courts conservative media and often seems to thrive on being a polarizing figure. For months, he has been stridently opposed to the efforts to promote the COVID-19 vaccine, making false or misleading statements about the vaccine and highlighting misinformation about vaccination efforts.

But all those polarizing statements appear to have come at a cost: Eight months ahead of the midterms, more Wisconsin voters have an unfavorable view of him than at any time in his political career, a recent poll found.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

At the same time, though, political observers said his prospects in November likely depend more on the national political environment than they do on media coverage of whatever his latest controversy happens to be.

Johnson’s “favorability has gone from high to low to high to low again,” said Charles Franklin, director of the Marquette University Law School Poll. “There’s been a lot of fluctuation since we started asking about him in 2013.”

Toward the end of Johnson’s first term in 2015, the Marquette poll found 29 percent of Wisconsinites had a favorable view of him while 33 percent viewed him unfavorably. He trailed Democrat Russ Feingold throughout the 2016 campaign, but improved steadily and ended that race just 1 percentage point down in the Marquette poll, and well within the margin of error. He ended up winning with just over 50 percent of the vote.

In the March poll, though, 33 percent had a favorable view of him and 45 percent were unfavorable; the net favorability of -12 is the lowest it has been in the poll. That affects his reelection prospects, Franklin said, but it hardly means he’s finished.

“These numbers are negative for him,” Franklin said. “They’re not where an incumbent would like to be at this point in the campaign. But he was in this position in 2015 and came back to win. Low favorability numbers are not a certain guide to the election outcome, and we have living proof of that in his 2016 comeback.”

Johnson has cultivated a following in conservative media

Johnson has long said he got involved in politics out of a desire to see former President Barack Obama’s health care law repealed. It was the central issue of his 2010 campaign for U.S. Senate; in his stump speech he called it the greatest assault on American freedom in his lifetime. In the Senate, he repeatedly voted to repeal “Obamacare,” including its popular policies such as protection for those with pre-existing conditions.

So it arguably shouldn’t have come as a surprise when he raised the idea of repealing the law last week in an interview on a right-wing podcast.

If Republicans want to repeal and replace Obamacare, Johnson said, “we need to have a plan ahead of time so that once we get in office, we can implement it immediately.”

Instead, the statement set off a flurry of coverage in national outlets and critical statements from Johnson’s Democratic opponents. Johnson even put out a statement walking back the comments, saying he meant it as an example of legislative priority-setting rather than a concrete statement of intent.

“I was not suggesting repealing and replacing Obamacare should be one of those priorities,” he wrote.

Johnson’s initial statements about the ACA represented a relatively unusual instance of Johnson seeming to be out of step with conservative media, which has largely moved on from the Obamacare repeal efforts that animated the 2010s, said Anthony Chergosky, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

“It’s clear that he really values being in line with the conservative media ecosystem and the Republican base,” Chergosky said. “He’s really attuned to the animating issues in conservative media.”

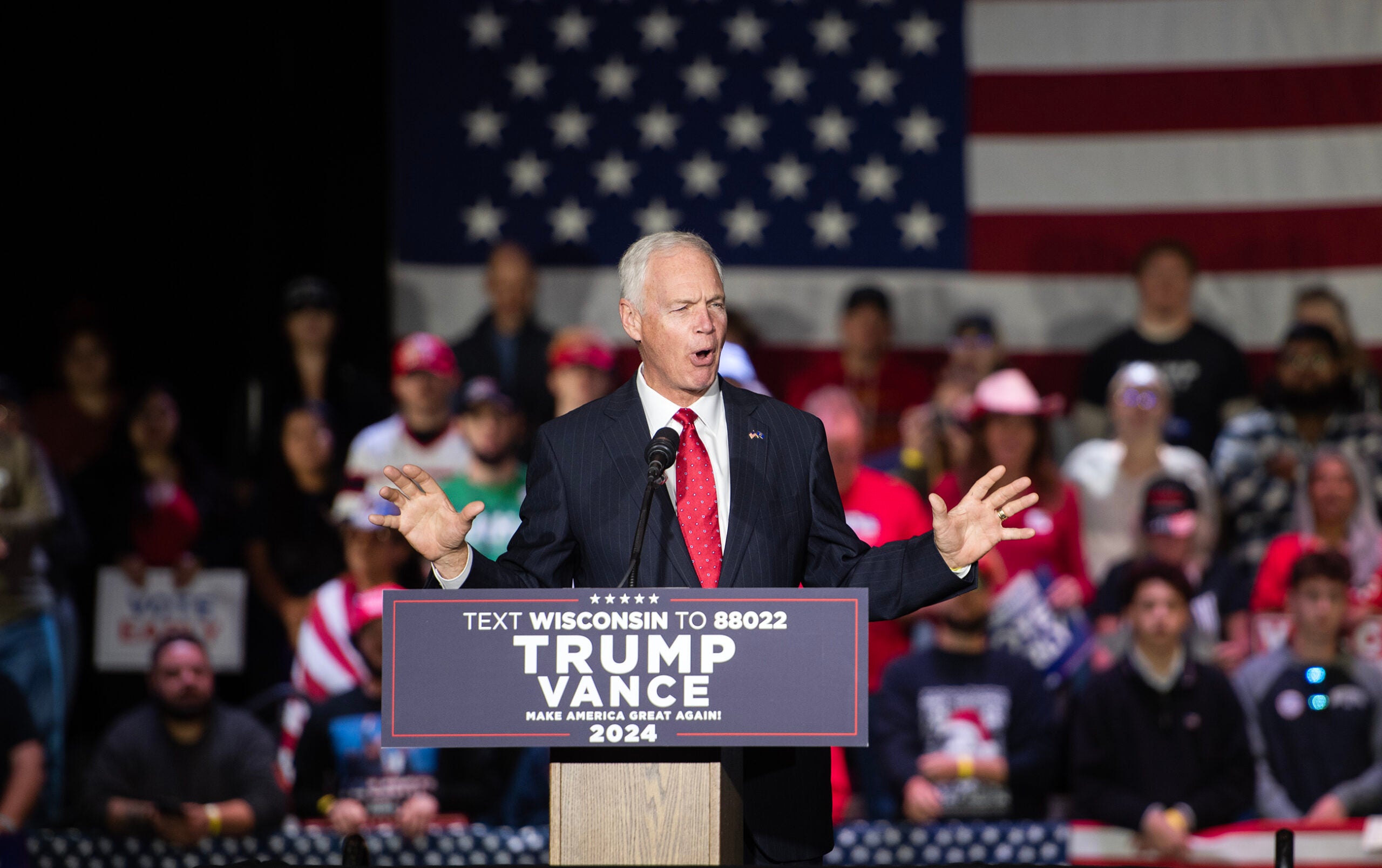

That affinity for conservative media has raised his national profile, Chergosky said, and may help ensure that conservatives in rural Wisconsin who voted in droves for former President Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020 turn out for Johnson, too.

“Ron Johnson has gained an intense following among Republican activists,” Chergosky said. “And that is going to serve him really well in terms of the intensity of support that he will get among a key part of the electorate.”

But in closely divided Wisconsin, he’ll need significant turnout in more moderate areas, including parts of suburban Milwaukee and the Fox Valley. And a risk for Johnson is that as he’s raised his national profile, his image in Wisconsin has also become more solidified than it was when he entered his first re-election campaign six years ago.

“I’ve been inclined to think that one of Johnson’s superpowers is the folks who don’t know him, that he can then reintroduce himself to anew during the campaign,” Franklin said.

That’s what happened in 2016. He started the year with 37 percent of Wisconsinites telling the Marquette poll they hadn’t heard enough about him to have a favorable or unfavorable view. By late October 2016, that number was down to 17 percent, and more people were favorable than unfavorable toward him.

This month, the number of people who said hadn’t heard enough about him was again at 17 percent, tied for its lowest level, even as he reached his highest-ever unfavorable rating.

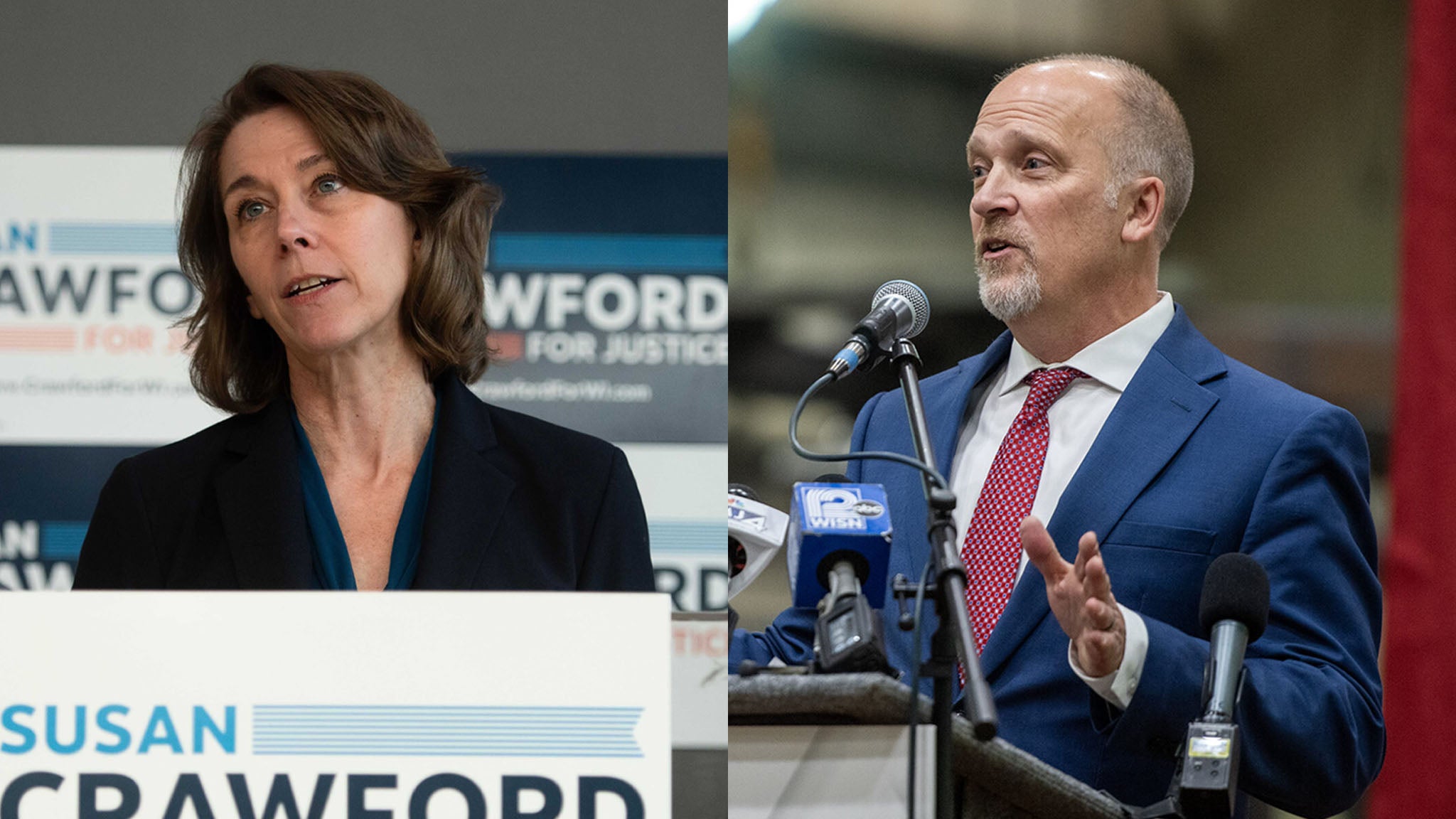

Democrats may face an uphill battle in November

Johnson doesn’t yet have a Democratic challenger; that candidate will be determined in the August primary. Nationally, political trends including poor approval ratings of Democratic President Joe Biden point to a challenging year for Democratic candidates at all levels. Polling experts said some conservative-leaning Wisconsinites who say they disapprove of Johnson today will not, in the end, actually be willing to vote for a Democrat.

But Democrats are doing what they can to tie Johnson to unpopular positions, especially on economics. Last week, the Democratic Party announced the “Self-Serving Johnson Tour” events that “blast Johnson’s agenda of higher tax hikes and more expensive health care.”

For his part, Johnson continues to associate himself with hot-button conservative cultural issues. Last week he met with a convoy of truckers and issued a statement bashing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the “COVID cartel.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.