A praying mantis sits eagerly at a dinner table, as a mustachioed and bow-tied waiter unveils a dish containing the steaming head of, well, another praying mantis.

“I take it the Honeymoon is over?” one caption reads.

“Shall I pack the rest of your date in a to-go box?” says another.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

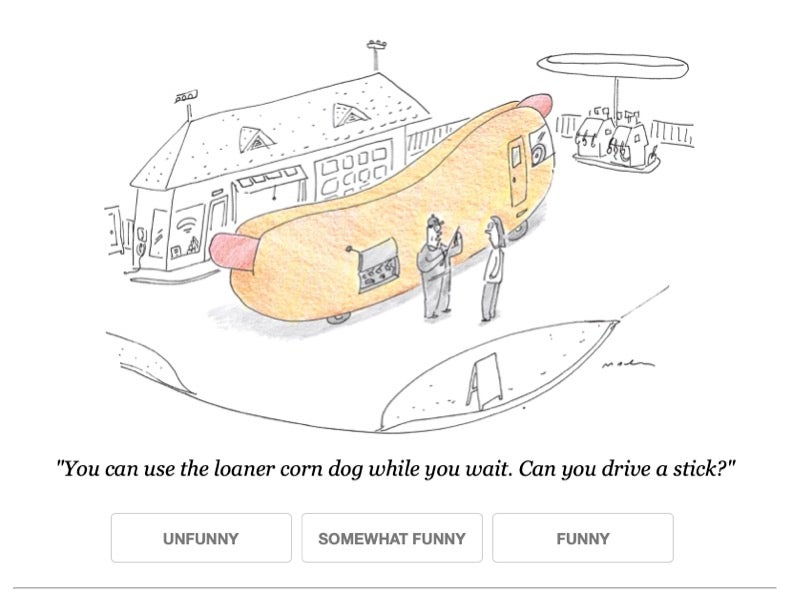

Under the caption sits a choice: unfunny, somewhat funny or funny.

Voters of The New Yorker’s weekly cartoon caption contest decide what witty line will appear in the magazine to accompany the praying mantis, an insect whose females notoriously decapitate its mates.

But which captions of the thousands of submissions voters are shown is not random.

The New Yorker relies on an algorithm from Robert Nowak, an engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Nowak said on WPR’s “The Morning Show” that the algorithm collects the ratings and over time pushes more successful captions to the top of a sorted list. It’s similar to how a search engine such as Google tracks how many times a website is chosen after a given search.

“So roughly speaking, the funnier the caption, the more ratings it receives, providing a more statistically accurate estimate of just how funny it is,” he said.

The partnership started when Nowak and one of his students saw a lecture on the psychology of humor that Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor for the magazine, gave at the university. Nowak saw it as an opportunity to test how different algorithms perform for such crowdsourcing activities, he said.

Mankoff shared some of The New Yorker’s data at Nowak’s request before ultimately letting the professor apply the algorithm to the real contest.

The New Yorker went public with the tool six years ago. Before Nowak’s algorithm, someone on staff would have spent about eight hours a week going through about 5,000 submissions, CNET reported in 2016.

Over the years, Nowak has tweaked the algorithm to better handle software engineering problems that have come up because of the scale of the data inputs.

“We also improved the way the algorithms work, so they’re more effective and more efficient and also a little bit more robust,” he said. “We put in some mechanisms that make it difficult for people to maliciously interact with the system. So, it’s a safer system.”

Nowak said his algorithm only uses the ratings voters submit. It doesn’t consider the words or captions themselves.

“The rest of it is based on statistical analysis, which is objective and as fair as you can make it,” he said.

The New Yorker isn’t the only organization using Nowak’s work. The U.S. Air Force and American Family Insurance also use the algorithm, and he said UW-Madison researchers use it to study human learning and decision-making.

He said “one of the most fun projects” he was involved with looked at how chemistry students studied visual representations of molecules. That work helped inform artificial intelligence tutoring systems.

“Using machine learning is about prediction, and so that’s the common theme,” he said. “We’re trying to predict something based on past observations.”

Some are trying to use artificial intelligence to win The New Yorker’s caption contest. Although The Pudding, a digital publication, was unsuccessful in their attempts to automatically generate winning captions, Nowak said getting a win eventually is “definitely possible.”

He said there’s some caution about using artificial intelligence for humor among bigger companies, like Amazon’s Alexa, because humor operates on the edge of appropriateness. But with all the data he has collected from the magazine, he has toyed around with “generating fairly funny captions automatically.”

“There’s a lot of potential there,” he said. “But we’re just starting on those projects.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.