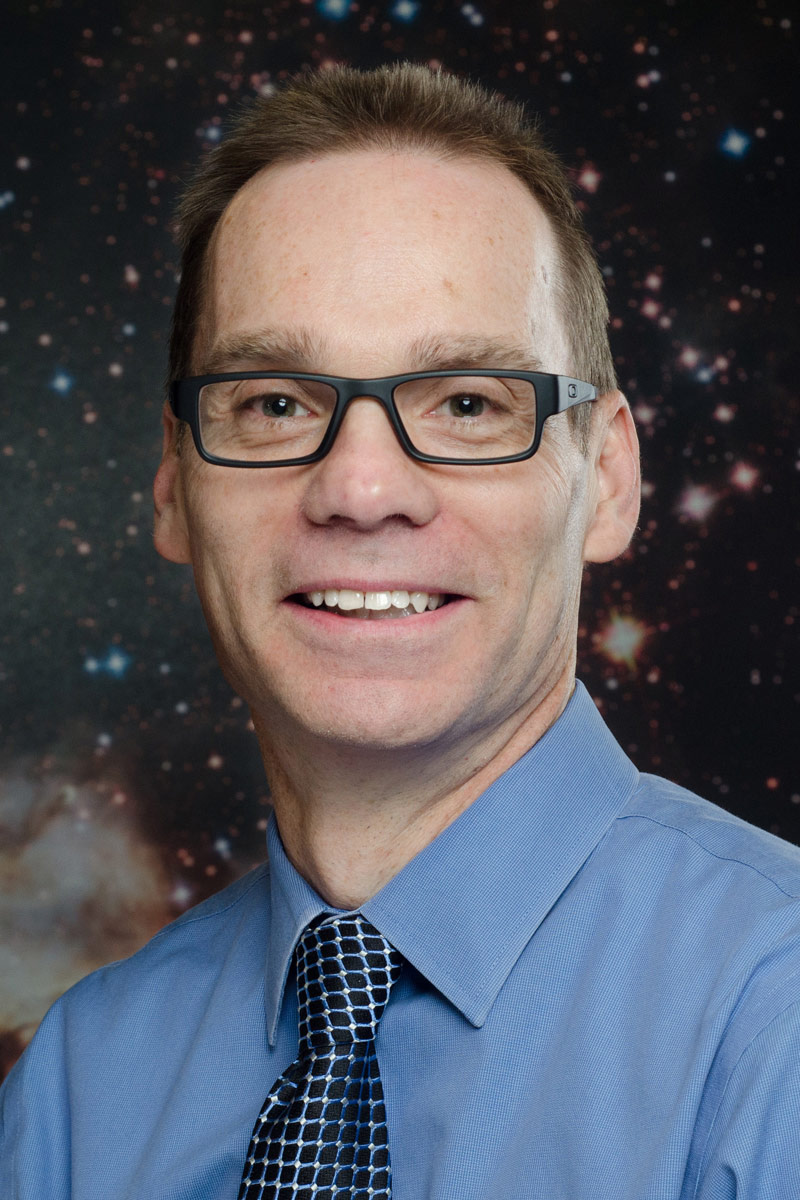

When Kenneth Sembach studied astronomy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he had no idea what heights he would reach—and the role he would have in NASA’s latest groundbreaking discovery.

As director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, the UW-Madison alum now leads the group conducting science and flight operations for the James Webb Telescope, which recently captured images of the earliest known galaxies in the universe. The White House and NASA on July 12 shared some of the first images from the telescope, calling the moment “the dawn of a new era in astronomy.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Sembach received his doctorate in astronomy from UW-Madison in 1992. Before his work on the James Webb Telescope, he also helped manage the Hubble Space Telescope, which left Earth in 1990 and still provides its own glimpse into the universe.

He recently joined WPR’s “The Morning Show” and discussed the next frontier of space exploration, comparisons to the findings from Hubble and his time studying in Madison.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Lee Rayburn: What was it like when you first saw the photos from the James Webb Space Telescope?

Kenneth Sembach: I just thought, “Wow. This is really something we haven’t seen before.” They are amazing, aren’t they?

LR: You worked on the Hubble Space Telescope. What’s the difference here?

KS: Webb gives us a different view of the universe than Hubble. That doesn’t take anything at all away from the magnificent images and data that Hubble has produced over the years and will continue to produce. It’s just that we’re looking at the universe in a different light with the James Webb Space Telescope. It’s infrared light.

LR: What does this all mean for space exploration?

KS: Our view of the universe is going to be changed forever, because now we have access to this infrared window that is allowing us to look in places in the universe where we haven’t been able to see before. We can peer deeper into clouds where stars are forming. We can look further back in time into regions that are really beyond Hubble’s reach.

LR: The James Webb Space Telescope took off from Earth last December. Where is it now? How far do you plan to send it?

KS: It launched Dec. 25, Christmas morning of last year. That was a really wonderful day to see the telescope finally arrive in orbit around the Earth and then get pushed out all the way to about 1 million miles from the Earth to a point called a “Lagrange Point,” which is a semi-stable point gravitationally on a line between the sun, the Earth and that point. So, relative to the sun and the Earth, the telescope always stays at approximately the same position. It actually orbits around that point 1 million miles from Earth.

LR: What’s the difference between taking pictures from out there and a terrestrial telescope?

KS: In the case of Webb, one of the most important differences is that the infrared light that it is sensitive to doesn’t actually reach the Earth’s surface at a lot of those wavelengths. And so, it gets absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere. So, getting above the Earth’s atmosphere gives you a clearer view and the ability to actually analyze that light.

Another important thing for all space telescopes is that, being above the Earth’s atmosphere, you don’t get the interference or the shimmering that you get when you’re looking at the universe from the ground. So, we’ve all gone out at night in Madison and Wisconsin. You get these nice cold winter nights where the sky is crystal clear, and it’s quiet and still and the stars just shine. But in the summer, they twinkle more. And that’s turbulence and disturbance in the air. That degrades the quality of the imaging. It blurs them out a little bit.

LR: What does the future hold for what we will learn from the Webb telescope?

KS: That (recently released) data is just the start. There is an entire year of observations planned right now. We did a peer review competition within the science community about a year and a half ago to select that program.

So, there’s a lot of exciting science. We’re observing right now, and we will be 24/7, 365 days a year for as long as the observatory is operational, which we hope to be 20 or maybe even more years.

LR: What is the Hubble Space Telescope up to these days?

KS: Hubble is still chugging away, making discoveries every day. It’s an amazing, amazing observatory, and it has been wonderful to work on it for so long. But many of the things that you’ll see observed with Webb have either been observed with Hubble before or will be observed with Hubble.

You want to get a multi-wavelength view of the universe because light is information, and the more light that you can collect at different wavelengths, the more information that you have to understand what you’re seeing.

LR: How did your time at UW-Madison help take you all the way to the Webb telescope and where you are today?

KS: I never had any idea at that time when I was in Madison that I would be in this position today. But I had a great four years in Madison. The astronomy department there is absolutely wonderful. I was introduced at that point to observations from space by my thesis advisor, Professor Blair Savage, and fell in love with the idea of being able to extract information from light, which is a technique called spectroscopy. I love the quantitative aspect of it but also the qualitative — what can you actually learn?

LR: It seems as though you still have an infinite number of questions that need to be answered somewhere out there, Ken.

KS: I think we do, and I think there are more and more every day.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.