Peter Krsko is an artist who creates sculptures and murals, and he gets his ideas from forms and structures that he finds in nature.

“My background is actually in biophysics and microscopy, so I find a lot of inspiration in these beautiful structures and tissues and formations in nature that are kind of invisible to us,” he said. “But if you discover them, they’re just fascinating.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

So it’s probably fitting that after moving to Wisconsin four years ago, Krsko took an interest in the state’s oldest nature-inspired structures: effigy mounds.

“I’m always fascinated by the geology of the Wisconsin landscape and also the mounds,” he said.

So, he asked WHYsconsin if he could learn more about them: “I always wonder where they exactly come from and who built them and when.”

He was particularly interested in discovering how the mound builders moved the dirt, and whether there is any connection to the glaciers.

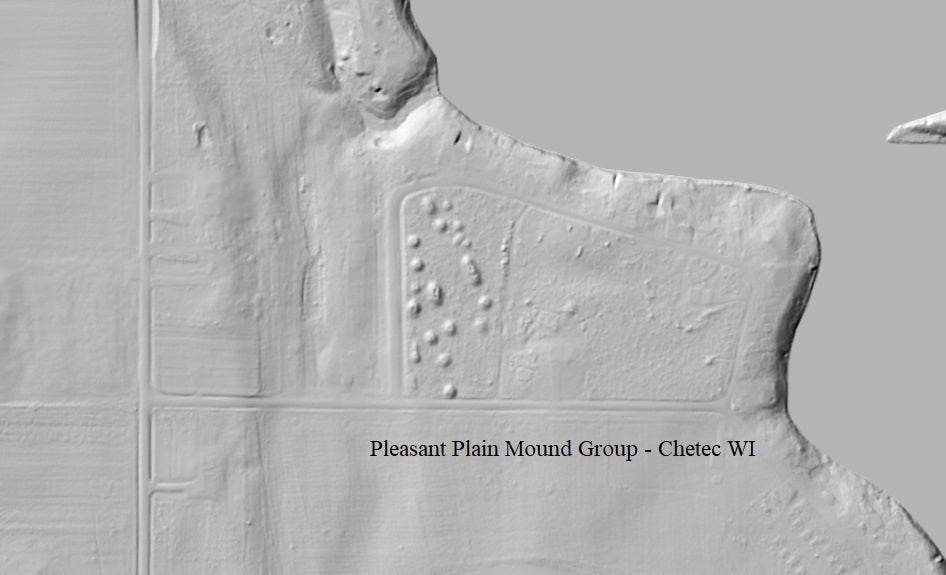

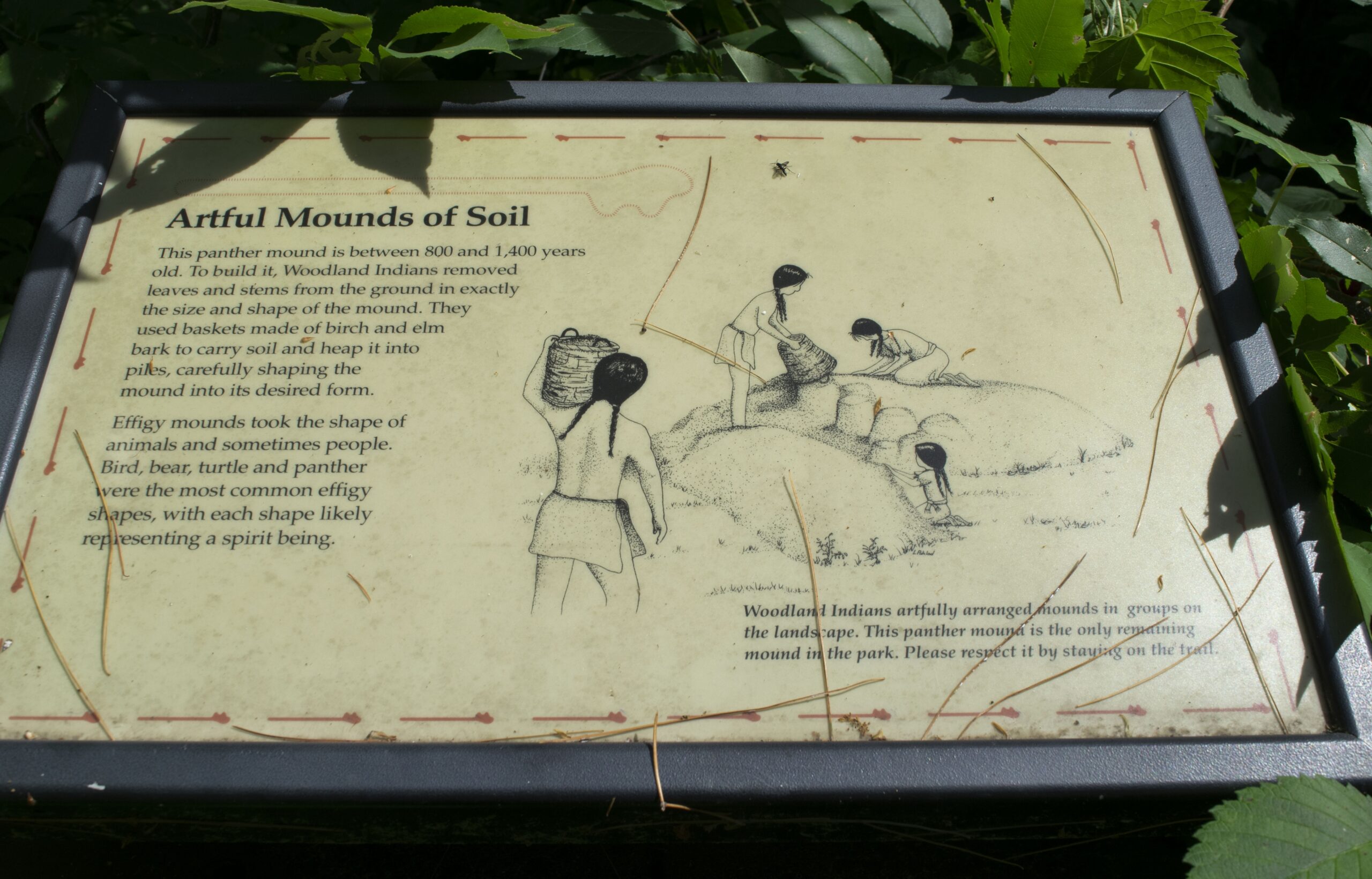

Effigy mounds are burial monuments made from the earth that take the shape of an animal or a spirit. That’s according to Wisconsin Historical Society staff archeologist Amy Rosebrough, who — through letters, maps and documents — found records of about 3,100 effigy mound sites in Wisconsin. Each site could have hundreds of different types of mounds.

But Rosebrough said there were likely many more. There are historical accounts of explorers saying they saw hundreds of effigy mounds, though no further records of those mounds exist.

“One of the early explorers called Wisconsin ‘a sculpted land,’ which should give you an idea of how many there were at one point,” she said.

Because the mounds were built in places where people like to live, such as on lake shores and stream confluences and even on good farmland, they became casualties of modernization. Once the area began to be settled by Europeans, the effigy mounds were plowed under, quarried, or they had homes built on top of them.

“There was even a sort of urban legend that went around for a while that mound dirt was very fertile, and so they were used as deposits of potting soil,” Rosebrough said. “If people wanted to benefit their gardens, they’d go in with a wagon and load the mound material and then dump it in their backyard.”

The Builders

Effigy mounds were built by Late Woodland people, as archeologists call them, from between A.D. 750 and 1200. These mound builders probably lived in temporary camps in structures similar to wigwams that could be easily dismantled and moved, Rosebrough said. They hunted with bows and arrows, gathered mussels and nuts, fished, and traded for stone.

They were preceded by Early- and Middle-Woodland people, who built conical and linear mounds. Evidence of these types of mounds appear all over the eastern half of the U.S. and the Great Plains.

“But here, for whatever reason, they said we’re going to build ours in the form of sculptures,” Rosebrough said.

Effigy mounds are found in Minnesota, Illinois and Iowa, but they’re mostly in Wisconsin and concentrated in the southern part of the state. Rosebrough hypothesized that it’s because of the vegetation there.

“This environment — this peak deer and turkey and bear production area where all the nut-bearing trees are, that’s like living at a Costco,” she said.

While there’s not a direct connection with the glaciers and Driftless area of Wisconsin and the mound builders, Rosebrough said the effigies are very sensitive to topography.

“The people who built them placed them on the landscape so that they flow right with the lay of the land, so it looks like they really are — if you could tip them up — real animals running up and down the hills and moving toward springs and going along the riverbank.

“People were doing everything they could to take advantage of what the landscape offered them, almost like a palette or canvas for an artist,” she said.

The mounds were truly sculptures, and they looked different based on whichever “artistic director” was leading the build.

First Nation Connections

It’s not known for certain which First Nations are direct descendants of the mound builders, but the Ho-Chunk Nation has steadfastly claimed the title, and that’s generally been accepted. Rosebrough said there’s a chance that there’s not a direct correlation between the mound builders and current tribes.

“We’re talking about 1,000 years back, so a lot can happen in 1,000 years,” she said, noting that the Ioway are believed to have once been one people with the Ho-Chunk and that split should have occurred after effigy mounds were built.

In recent years, the Ho-Chunk have divulged more information about their relationship to the effigy mounds.

Prior to that, no one apart from the Nation knew what they meant, how they got there, who was in charge of caretaking, and what they were used for and when, said Samantha Skenandore. She’s an attorney at Quarles & Brady and a member of the Ho-Chunk and Oneida Nations. She has spent almost two decades working with First Nations all over the country helping to preserve cultural sites.

“The Traditional Court has told me umpteen times that every time we expose this information, it gets sabotaged, ruined or irreversibly damaged,” she said. “Their lesson in decades passed down through oral tradition is not to tell anybody about these sites and what they mean.”

Ho-Chunk’s Traditional Court comprises the eldest living male relative from each of the 12 clans. It’s these men who have constitutional power over issues of traditions and customs, Skenandore said.

But in the 1990s, Skenandore said the Wisconsin Historical Society challenged the Nation with a request to catalog the locations of these sacred sites. The goal was to identify these sites that were already protected under state law. The mounds first gained state protection in 1985, designating these as burial sites. Previous to that, numerous mounds were lost to agriculture, quarrying, construction, curiosity or a lack of awareness.

The state doesn’t know exactly where all of these sites are. But through an itemized inventory created by the Ho-Chunk Nation, the state is pinged whenever there is a chance they’ll be working on or around sacred sites. The Nation and state then work out solutions on a case-by-case basis.

In 2016, there was some debate in the state Legislature about whether laws protecting these sites should be eased. What resulted was intense pushback from Native Americans, historians and others. Proponents for loosening the law eventually dropped the issue, and the law protecting these sites was actually strengthened.

Sacred Sites

Rosebrough comes from a family of monument builders. The Rosebrough family owned a tombstone business in St. Louis, and her great-grandfather was a tombstone maker.

“So the idea that people would craft art into monuments for the dead is something that’s always interested me,” she said.

And similar to modern tombstones that reveal the family name of the deceased, Rosebrough said these effigy mounds function in much the same way.

“These are saying Bear clan, Thunderbird clan, Hawk clan, Pigeon clan,” she said. “They’re telling you about the person inside, that they’re an important person and that they belong to an important family.”

People who were buried in effigy mounds were more likely to have the mound to themselves. They’re also less likely to have broken bones or serious injury. That’s a shift from people buried in conical mounds, where up to 50 could be buried in one location.

Not all effigy mounds that were excavated before the sites were protected had evidence of human remains, but that could be because the bones have since disintegrated. Skenandore said at least 75 percent of the mounds that have been excavated in Wisconsin and beyond contain human remains.

“When we talk about them, we have to assume for the most part, we’re talking about human burials that are protected by Wisconsin burial law and certainly other federal laws for tribes,” she said.

Skenandore has done work for tribal jurisdictions all across the U.S. and said that each nation with these types of earthen works describes a connectivity to the larger universe and to even older ancestors such as the Hopewellians, which describe an entire culture that predates the mound builders, and ties together mound cultures that extend into Indiana, Ohio and New York, with the Seneca Nation, the Iroquois Confederacy tribes and the Ho-Chunk and Iroquois Hopewell.

“That connectedness is all under the ground and above the ground with these 3D mounds,” Skenandore said. “So when you think about it from a bird’s-eye view, the meanings of the mounds are much larger than what we see walking down a trail here in Wisconsin.”

In the mounds where remains have been found, it appears as though the dead would be buried near the heart of the animal.

Rosebrough said the animal represents the founding member of the clan.

“Some of the funeral and mortuary ritual that’s been made available to Euro peoples talks about the spirit of the deceased becoming one with the clan ancestor,” she said. “There’s a wonderful oration from a Bear clan member’s funeral where they talk about him traveling the road of the dead and gradually transforming into a bear as he moves.”

Lost to History

A group referred to by historians as the Cahokians, or Middle Mississippians, arrived in this area around AD 950, and had a big impact on effigy mounds. Near modern St. Louis, Cahokia was the closest thing that North America had to a city, with tens of thousands of inhabitants.

Cahokians eventually settled on the Mississippi River and probably intermarried with the local populations.

There’s a chance that the Cahokians had an impact not only on pottery and farming techniques but also on religion. Effigy mounds weren’t built long after their arrival.

But the effigy mounds are peppered throughout Madison’s landscape, and especially on UW-Madison’s campus. Observatory Hill was once home to a village called Wakandjaga that was surrounded by 12 burial mounds. Two of those mounds are left.

The university long had a tradition of meeting with tribal leaders to discuss how to embed a cultural education in the school’s curriculum, but that practice ended, Skenandore said. A renewed effort got underway in September last year, which included placement of placards throughout the university’s campus that explain the mound sites and their significance.

Skenandore said she’s grateful that her ancestors created something that can be seen, and as a result is valued and protected.

“Because there are sacred sites out there in the desert that have just as much meaning, but they don’t check those boxes,” she said.

In his book, “Spirits of Earth: The Effigy Mound Landscapes of Madison and the Four Lakes,” author Robert Birmingham writes that these mounds are living and animated connections between worlds.

“One gets the impression that the manmade constructions were not simply built as static symbols on vacant land, as one might paint religious representations on a blank canvas, but were built to be alive, actively bringing together the natural and supernatural worlds,” he writes.

The Ho-Chunk tell the story of their ancestors searching for direction and foundation. They pray to their creator, Mauna, who answers them. He tells them that he’ll put medicine in the earth in the form of these mounds.

“Our story says that the creator built them for us and had them rise up and show us who we are, where we’re from and that those will always be there for us,” she said.

That medicine is for all of us, Skenandore said. So, go sit at the Bear mound at Henry Vilas Zoo. (Unless you’re a woman who has your period. You should stay away from the mounds during that cleansing period — You’re too powerful during that time and shouldn’t be around the dead, Skenandore said.)

Stay as long as you need. Set out meals or tobacco for the spirits.

“Protecting them is one thing. Not destroying them is one thing,” she said. “But feeding them and keeping them alive is a whole ‘nother thing.”

This story came from an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it in a future “Wisconsin Life” segment.