The Wisconsin Department of Corrections is confining prisoners to their cells due to a lack of staff to operate facilities at full capacity — a practice unfolding at more prisons than officials previously acknowledged.

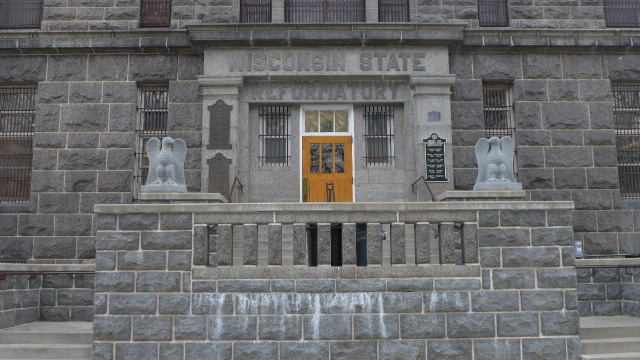

The New York Times and Wisconsin Watch have learned that Stanley Correctional Institution — a medium-security prison in Chippewa County — has limited prisoner movement for the past year. Department officials previously said only Waupun and Green Bay correctional institutions were doing so.

Meanwhile, in Waupun, 30-year-old Tyshun Lemons became the second prisoner to die in custody since the department instituted lockdown conditions in March. DOC spokesperson Kevin Hoffman said a medical examiner has yet to determine a cause of death, but attorney Lonnie Story, who has been in contact with the Lemons family, said Lemons died by suicide. The death follows the June suicide of Dean Hoffmann.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In August, more than two dozen inmates incarcerated at Waupun described to Wisconsin Watch and The New York Times squalid conditions inside the prison, including dirty water, limited opportunities for recreation and showers, canceled family visits and a dearth of timely access to medical and mental health care. Men were so desperate for medical care, they said, some have cut themselves or threatened self-harm to be seen by nursing staff.

Elsewhere, prisoners inside Green Bay Correctional Institution, facing restricted movement since June, describe similar conditions, including rodent infestations.

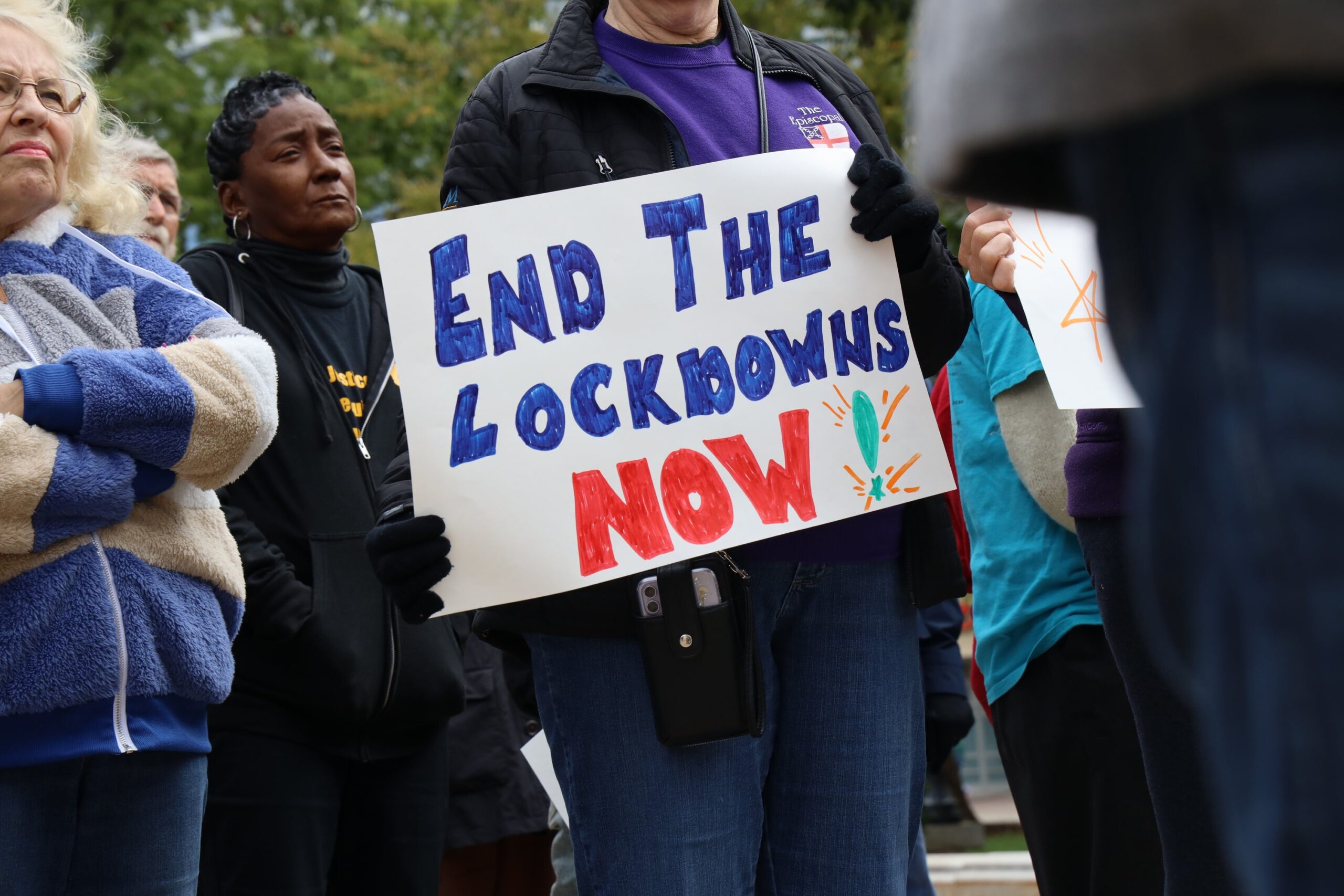

The department refers to the restrictions not as “lockdowns,” but rather “modified movement,” because officials can adjust the restrictions over time. Some prisoners have been allowed at times to leave their cells for work, appointments or recreation. But experts call lockdown an appropriate term for conditions in Waupun, where prisoners in recent months have been confined to their cells for up to 24 hours each day, going without family visits and regular access to showers and recreation.

Waupun staff have themselves used the term lockdown when refusing medical care.

“No optical during lockdown,” read a note from Waupun medical staff, in response to a request from a man seeking medical attention for eye pain and blurry vision.

Story, who is representing several Waupun inmates in a class-action lawsuit, said he’s shocked to see the Waupun lockdown approach seven months. In 1983, Waupun prisoners were locked down for just three days after seizing control of buildings, taking hostages and setting fires.

“These men are already serving a sentence, and these conditions are going above and beyond that. It’s almost as though they’re receiving a second sentence,” Story said.

Hoffman, the DOC spokesperson, said the department is incrementally easing the restrictions in Waupun and Green Bay. In Waupun, for example, the number of prisoners allowed out of their cells to work jobs within the facility has tripled, and behavioral health groups have resumed. In Green Bay, prisoners have been allowed to resume chapel services, he added.

The lockdowns come amid a staffing crisis in Wisconsin’s prisons. At Waupun, more than 53 percent of sergeant and correctional officer positions remain vacant. It’s the shortest-staffed prison in a system averaging a 32 percent vacancy rate.

Initially, prison officials denied any link between lockdowns and staff vacancies, telling Wisconsin Watch and The New York Times that threats and assaultive behavior prompted the restrictions.

“Staffing is not the reason for the modified movement,” a DOC spokesperson said in July.

Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and department officials have since acknowledged that vacancies hinder efforts to resume normal operations.

“Staffing did not cause the modified movement,” Hoffman told Wisconsin Watch in September. “But staffing does factor into the facility’s ability to lift these restrictions because adequate staffing is required for escorting, responding to threatening behavior, and maintaining the safety of everyone at (Waupun).”

Department officials have also shared conflicting information about how many prisons face restricted movement. In July, Hoffman said only two prisons met that criteria. DOC Secretary Kevin Carr repeated that information to lawmakers during his September reappointment hearing.

But The New York Times and Wisconsin Watch have since obtained a memo authored by Stanley Correctional Institution Warden Chris Buesgen announcing that a “modified movement phase” would begin Nov. 7, 2022.

“While it is understood that these changes will not be favored, they are necessary at this time given the current staffing shortage,” Buesgen wrote.

Stanley’s 44 percent vacancy rate for sergeants and correctional officers ranks third highest among Wisconsin prisons, department data show. Stanley prisoners say they’ve spent 18 hours a day in their cells with reduced access to the day room, where they can use the phones. They had previously been allowed to spend about half of each day outside of their cells.

Lack of staff has so hobbled the institution that educators must supervise the yard during recreation time. Prisoners say they’ve missed education time due to teachers being assigned other duties within the institution.

Hoffman said the department has eased some restrictions at Stanley in recent months, including increasing recreation time. It is not uncommon for education staff and other non-uniformed personnel to assist with supervision and recognize emergencies, he added.

“Bottom line, security is everyone’s role in an institution,” Hoffman said.

Multiple prisoners and their family members say they are facing increasing discipline during the restrictions, with some drawing citations for infractions as small as eating a turkey sandwich on the stairs or speaking with someone during a video visit who is not on an approved visitor list — even if that person is an infant being held by their mother. The infractions could land a prisoner in solitary confinement.

Among the biggest effects of the restrictions, said Emily Curtis, whose loved one is incarcerated in Stanley: less time to speak with him at visits and on the phone.

Research has long shown that connections with family and friends can improve a prisoner’s likelihood of successful reintegration after release.

“You might only talk to a loved one twice a week,” Curtis said. “They are constantly living within such a negative space there and a lot of times we are the only positive thing they have, the only hope and encouragement they have, as we try to bring them out of the dark place they’re in.”

“We are not numbers on a piece of paper,” said Curtis’ loved one, Martell Rogers, who while incarcerated has built a real estate company with the help of people outside of the prison.

“We are not items that you can bind up and mistreat and think everything will be fine when we’re set free. You cannot separate us from our humanity,” Rogers said.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.