Betsy Bloch doesn’t remember the end of 2020, or any part of January 2021.

She remembers getting in the ambulance on Christmas night. She can remember the next day, being taken by helicopter to UnityPoint-Meriter Hospital in Madison. She caught COVID-19 on the tail end of Wisconsin’s first big wave of new infections and spent January sedated in a medical coma.

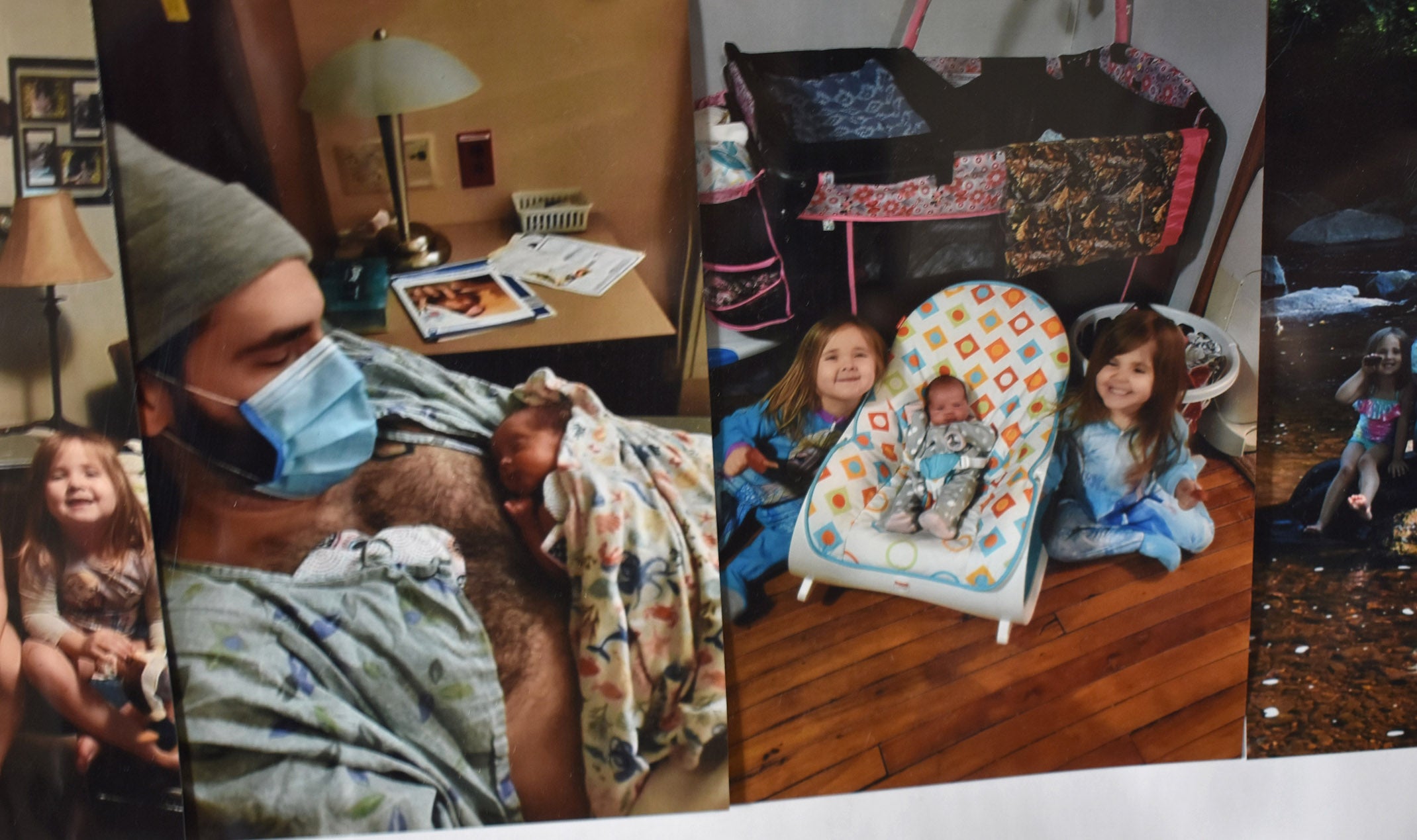

Bloch was seven months pregnant when she went into the hospital. Doctors needed to medically sedate her, and when they did that, the baby’s vital signs began to crash, Bloch said. Just days after she was admitted, she gave birth to her third daughter, Jennifer, by cesarean section.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“I was told in February that I’d had the baby,” she said. “They didn’t tell me what day.”

The hospital sent Jennifer, who was about two months early, to the newborn intensive care unit. Bloch’s condition was worsening, and her lungs weren’t supplying her body with the oxygen she needed. Doctors would later learn that in addition to COVID-19, she also had contracted blastomycosis, a rare fungal infection that attacks the lungs. That infection likely compounded the effects of COVID.

It would be months before Bloch came home, months before she held her daughter or even saw her in person instead of on FaceTime. And the life she came home to in Athens, a small town in central Wisconsin, was different. Her family was different, and she was different. And she and her husband would spend the next year worried about their medical bills and working on her recovery.

Wisconsin has confirmed almost 1.4 million cases of COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. More than 12,000 people have died. But even among those who have recovered, the disease has left lasting scars. Some suffer from long COVID; others have lost family members, jobs or social connections in the last two years.

Today, the rate of new COVID-19 infections in the state is as low as it was nearly a year ago and is still declining. Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control in recent weeks has issued new, relaxed guidance on mask-wearing and quarantining. In the words of one science writer, the pandemic is “inching toward an endemic.”

Bloch is also moving forward.

“I’m trying to create a new life and put this behind me,” she said in February.

But in the same way the pandemic has left changes small and large across Wisconsin, the nation and the world, Bloch’s case also demonstrates just how much a fight with a serious illness can affect a family’s life. There are things about her sickness she can put behind her. But there are also things in her life that will never be the same.

An isolated, painful hospital stay, followed by a difficult homecoming

From the time his wife was hospitalized, Justin Bloch tried to keep some sense of normalcy for their two daughters, 5-year-old Amelia and 4-year-old Raina.

“I kept pushing on every day,” Justin said. “Especially when the kids were around, just trying to be a base for them.”

They were not sure how Betsy contracted COVID-19. Luckily, the rest of the family didn’t get sick at the same time.

Because of the hospital’s pandemic rules, he mostly visited Betsy virtually. In the first month, he saw her in person once, while she was under sedation. After Jennifer was born, he could see his daughter in the NICU, but only under strict visiting protocols and, at first, after a nearly three-hour drive from their central Wisconsin home to Madison.

For a time, he couldn’t work. In the mornings, he took his daughters to day care, then spent the day waiting for medical news, talking with family, trying to distract himself.

For much of her time in the hospital, Betsy’s family, including Justin and her mom, Kim Engel, spent every day afraid of the call that would tell them she died. After Betsy had Jennifer, Betsy’s condition worsened. They told Engel that despite the risks of moving her, they would need to transfer Betsy from Meriter to UW Health Hospital. Her oxygen levels were falling, and they believed she might require an ECMO machine, a life support system that would add oxygen to her blood. The pandemic had made ECMO machines scarce, but UW Health had one available for her.

“They said: We can’t wait until the last minute,” Engel said. “She has to be there if she’s going to be put on it.”

Doctors put her on the ECMO machine as soon as she was transferred.

Baby Jennifer was in the NICU in Madison for about three weeks, then was transferred to a Wausau hospital for about a week, much closer for Justin. By late January, Jennifer was home.

For Betsy, though, the months that followed were the most agonizing of her life. She felt as if she were burning from the inside. The air-conditioning in her hospital room was set at 55 degrees. Nurses brought her cooling blankets.

“They had six to seven ice packs put around me, and they had to change them out because they would just melt,” she said.

She remembers a scan of her lungs that showed how depleted they had gotten. If a scan of healthy lungs shows a large, dark cavity, she said, “mine was like looking through a cloud. It was just white.”

Her despair was not just physical. She felt uncontrollable anxiety. She remembers looking up mortality rates on her phone from her hospital bed, thinking she probably wouldn’t leave alive. She tried kicking off the ECMO lines. She said she attempted to kill herself when she felt she couldn’t live through the pain.

But she did, and she began to improve. The lung scans began to show pockets of black. She could breathe on her own.

“They still weren’t normal-looking, because they’re not going to be,” she said. “My right lung is very, very scarred. And (the doctors) said that might not go away.”

In March 2021, Betsy was released from the hospital, and finally met her baby. It was not a made-for-TV moment. She hadn’t been able to bond with her child in the hospital. And even though she was home, she wasn’t close to healthy yet. She wasn’t eating. Her thoughts turned to dark places.

“I would have panic attacks if the kids would get too loud,” she said. “It sounds horrible, but when you’re in a hospital room, with its beeps and boops … you get used to that.”

Holding Jennifer felt wrong. Betsy burst into tears at the sight of Raina, who seemed to have grown into a different child since Betsy had been gone.

It took her months to bond with the baby. But again, she made small, incremental steps forward, with the support of her family. She got better.

Family, community supported Bloch family through ‘trying year’

In October, Engel organized a community fundraiser for Justin and Betsy. Church members, family friends and community members gathered in the town of Merrill for food, music and raffles, all to raise money for all the income they lost while Betsy was hospitalized and Justin wasn’t working, as well as what they worried could be crushing medical bills.

Raina and Amelia played hopscotch and rolled down the hill outside the town hall. Jennifer slept in a baby carrier. The family said they felt supported by their community, who came together to show they cared about what all the Blochs had been through.

“It’s been a trying year,” said Jerry Engel, Betsy’s father. “But it turned out for the good.”

By the fall, Betsy had been able to go back to work at Weinbrenner Shoe Company in Merrill. Justin, formerly a dairy farmer, had found a maintenance job with the Athens School District. Engel was caring for her own aging mother in Merrill, and worrying a lot less about her daughter.

In December, nearly a full year after Betsy got sick, she finally received word about her medical bills. Though she had been affected by both COVID-19 and blastomycosis, the state attributed her hospital stay to COVID-19, and wrote off the cost of her expenses: the helicopter; the ambulances; the months spent connected to the ECMO machine. The family had almost gotten used to the underlying anxiety of worrying about whether they’d spend the rest of their lives in medical debt.

For Betsy, finding out they didn’t owe anything came with its own kind of survivor’s guilt. The money from the fundraiser was still a lifeline, as her sickness had meant months of lost income for the family and plenty of debt. But after all the months of waiting for the next bill, she almost couldn’t believe it when it didn’t come.

She knows she’s changed since she got sick. It’s not just the tracheotomy scar, the inhaler she needs now. She’s also quieter, she said, and a bit more inwardly directed.

“She didn’t come home the same person she was when she left,” Justin said. “You go through a life issue like that, you’re not the same person anymore.”

But Betsy also said she feels fortunate to have come out on the other side of her ordeal.

“I do have a long way to go,” she said. “But I’m here.”

This week, WPR is bringing you stories reflecting on the last two years of the pandemic. They include stories on long haulers, masking, health care workers, education and work. For more stories on COVID-19, visit wpr.org/COVID.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the name of Jerry Engel.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.