Culture critic Mark Harris on the unique and lasting legacy of director Mike Nichols. Also, Zackary Drucker on the fascinating true story behind HBO’s docu-series, “The Lady and the Dale.” And bassist Bruce Thomas talks about playing with Elvis Costello.

Featured in this Show

-

The Lasting And Influential Legacy of Mike Nichols

The lasting, varied and inimitable legacy of director Mike Nichols began when he was a boy. In his gripping and comprehensive biography – “Mike Nichols: A Life” – journalist and author Mark Harris traces the icon’s origin story to Nichols’ own preferred starting point when he was only 7 years old.

That was in 1939 when Nichols fled Germany ahead of the war and arrived in America with his younger brother. Harris tells WPR’s “BETA” that Mike had a rough start to his new life in America.

“Mike had lost all of his hair because he had a reaction to a (whooping cough) vaccination that robbed him of the ability to grow hair for the rest of his life. So he really began life in New York City as a refugee and a kind of double outsider, a kid who didn’t sound like other kids, a kid who didn’t look like other kids. And then at a fairly early age, his father died,” Harris said.

It’s apt then, that Harris opens his biography with an epigraph quoting Nichols: “Disaster can reorder our lives in wonderful ways.”

Harris says that Nichols used that outsider standing to sharpen his power of observation. That skill set was the ignition point that led Nichols to not only master, but innovate in both comedy and directing.

“Mike had to look at other kids and assess who are the popular ones, how do they act,” Harris explained. “That kind of precision, that time he took to notice things, really fueled his first big career before he ever became a director, which was as an improv comic performer with Elaine May. I mean, all of their comedy depended on really close observation of the little tics and vanities and insecurities and pretensions of the people that they were playing.”

After meeting each other at the University of Chicago, Nichols and May worked together on a series of stage performances and sketches that made them realize their nearly perfect suitability for one another. They laughed at all the same things and quickly worked out that they complimented each other brilliantly. The pair ended up becoming one the most influential comedy duos in history.

Harris says that Nichols carried that same specificity that made him successful performing into his next foray of directing for the stage and screen.

“(Nichols and May) had to play it in a way that was recognizable to an audience, and I think that once Nichols stopped being a performer in 1962 and became a director a year later, he carried that over into his work with actors. It’s the kind of performance that he really liked to draw out of an actor, something very specific and very real. And it’s also the kind of performance that he could help an actor find their way to,” Harris said.

In 1966, Nichols directed his first film, the adaptation of the Edward Albee play “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.” The film starred real-life partners and superstars Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Harris says that Nichols forged a phenomenal working relationship with the larger-than-life actors by creating an us-against-the-world attitude with them.

“Mike’s attitude was sort of complicity. He would say, ‘You and I are partners in this creative thing that we’re going to do. And our job is to push everyone who wants to interfere away and just try to do the best thing we can do. My job is to try to get the best performance from you and your job is to just come ready to do it,’” said Harris.

What made this feat even more remarkable was that in addition to being the center of the Hollywood universe, Taylor and Burton had drastically different approaches to acting.

“Burton was very serious actor. He’d done a lot of stage work. He had done a lot of classics. Elizabeth Taylor had never even been in a rehearsal before,” Harris said. “Yet they both trusted him completely. And that was a hallmark of Mike’s work with actors throughout his entire career, that he knew not just what every actor needed, but the different thing that each actor needed to create that kind of trust.”

Nichols is probably best known for his 1967 film “The Graduate,” starring a then-unknown Dustin Hoffman. While he vouched and fought for Hoffman to play the part of Ben Braddock, their relationship wasn’t as rosy as the one Nichols enjoyed with Taylor and Burton.

“When Hoffman wasn’t getting something or when Mike wasn’t happy with what he was getting, he could be really tough. Dustin Hoffman told me by the end of the shoot, ‘I don’t think they really cared whether I lived or died.’ And I think he was half-kidding,” recalls Harris.

“The Graduate” would go on to garner Nichols an Oscar for his directing and became a landmark film still influential today. Harris argues that its sustaining power isn’t built on being a time capsule of the late sixties or for the titular Simon and Garfunkel pop song, but for Nichols’ ability to again capture that cross generational humanity.

“I think one really unusual thing about ‘The Graduate’ is that it can be taken different ways depending on the age you are when you see it. I mean, I first saw ‘The Graduate’ when I was younger than Benjamin, and he seemed like a real hero to me. And as you go through your life, in many ways, he becomes a less and less sympathetic character. When I was in my 40s, suddenly I thought the heart of this movie is Anne Bancroft’s character, Mrs. Robinson,” Harris said.

“Nichols always really insisted, and so did Buck Henry, the screenwriter, that it was really a movie about a privileged, cosseted young man who was slowly beginning to rebel against the materialism and affluence that he had been absolutely surrounded by from the time he was a child. And I think that theme stands the test of time a little better than a very specifically late 1960s take on youth versus middle age would have,” he added.

In the acknowledgements of “Mike Nichols: A Life,” Harris admits that during the writing process, there wasn’t a day that passed when he didn’t wish he could ask Nichols — whom Harris had in fact interviewed earlier before his death in 2014 — one more question.

“I’m not sure what the one question would be, but I know that the first word of the question would be ‘Why’,” Harris said. “There were places where it would have been really illuminating to hear what he thought about why he did something. Without that, it was my job to do everything I could to figure it out anyway.”

-

The Lady And The Dale: The Stranger Than Fiction Life Of Liz Carmichael

“Liz Carmichael, in the words of her daughter, was born a farm boy who was too smart for his own good,” recalls Zackary Drucker.

Drucker is the co-director and executive producer of the HBO docuseries about Carmichael, “The Lady and The Dale,” which recounts her life as a transgender woman in the 1960s and ’70, a fugitive from the law and a con artist car company executive.

Drucker recently spoke with Doug Gordon of WPR’s “BETA” about Carmichael’s complicated, stranger-than-fiction legacy.

The Lady

“Liz transitioned in her 40s, in the mid-1960s, but was assigned male at birth and had a pretty mischievous and bombastic life as a petty criminal,” Drucker explained.

When that criminal activity led to a federal counterfeiting charge, Carmichael, who was born Jerry Dean Michael, went on the run from the FBI with her fifth wife, Vivian and their five children. Soon after, she staged a bloody car accident to fake her own death.

“She did transition in that period of time, which was authentic to who she was and who she felt herself to be, but it also was an effective way to disappear,” Drucker explained. “And sure enough, we didn’t include this in the series, but we found in FBI files that were later unsealed, that in 1970 the FBI continued to pursue and follow Vivian.”

“And they even note in their file that Vivian is now living with a woman named Elizabeth Carmichael. But they didn’t have it in their imagination that Liz Carmichael was Jerry Dean Michael, the person that they were looking for,” she continued. “So it literally says in these FBI files, Vivian is living with Elizabeth. No information can be tracked on Jerry Dean Michael.”

While being interviewed for the series, Candi Michael, one of Liz Carmichael’s daughters, recalled what life was like for her family during that time.

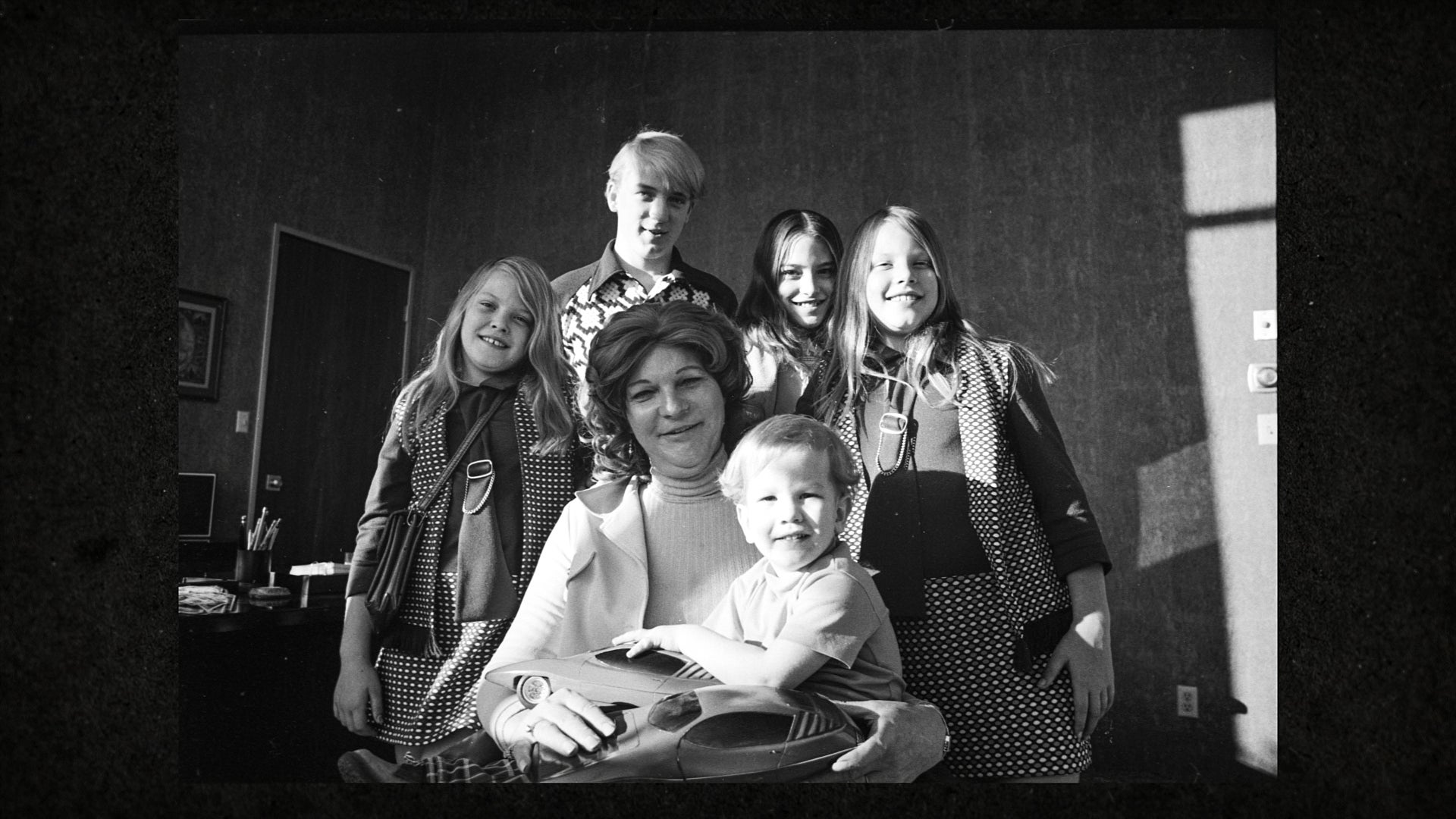

Elizabeth Carmichael with her family. Photo courtesy HBO “To me, a normal thing was just getting used to a house and finally getting friends, and then sneaking off in the middle of the night. The kids piling in the car and winding up sleeping in the car on the side of the road 10 hours later in another state,” said Michael.

“I would have a hard time imagining what that would be like as a child and how destabilizing it would feel,” admitted Drucker. “They were a family on the run. They lived under assumed names.”

The Dale

By the 1970s, Carmichael and her family had made their way to Los Angeles. There, she met local inventor Dale Clifft.

Clifft had recently modified a motorcycle to make it weather-proof for year-round riding. The result was an enclosed cockpit on three wheels that was much more fuel-efficient than a standard passenger car.

He gained some notoriety riding this vehicle around,” said Drucker. “Liz bought the option from Dale and took it and ran.”

With the rights to the “Dale” in hand, Carmichael started 20th Century Motor Car Corp. She hired engineers, built a prototype, put it on display in the lobby of her new corporate headquarters, and began aggressively marketing the concept.

“Liz made so many outrageous claims about the car that it was kind of aspirational,” Drucker said.

She claimed The Dale was made from a space age plastic several times stronger than steel, adding that she’d personally driven the vehicle in to brick walls at up to 50 mph without structural damage. She claimed the car was more stable than traditional four-wheeled vehicles and would average over 70 miles per gallon.

Elizabeth Carmichael with a Dale prototype. Photo courtesy HBO And with a price tag of only $2,000, the striking bright yellow, ultra-modern vehicle generated a lot of early excitement, even appearing as a prize on “The Price Is Right.”

Carmichael began selling options on the vehicle, which was still in the prototype phase and not yet in production. In an interview during that time, Carmichael confessed, “Frankly, I never thought people would buy a car without driving it first, but apparently they will.”

The Fallout

Behind the scenes, finances began to unravel as the money from advance orders was illegally funneled in to other areas of the business, workers were paid with stacks of cash, and shady characters frequented Carmichael’s office.

Scrutiny began to mount. Local TV reporter Dick Carlson and producer Pete Noyes began doing investigative pieces on Carmichael and the Dale.

“They, I think, were immediately skeptical about Liz’s claims of the Dale and paid her a visit,” said Drucker. “Ultimately, Dick Carlson is the person who outs Liz Carmichael.”

In one of his reports, Carlson revealed that Carmichael was actually a fugitive named Jerry Dean Michael. Carmichael would soon serve a prison sentence for her old counterfeiting charge, and be put on trial for grand theft and securities violations relating to the Dale.

Elizabeth Carmichael with her family. Photo courtesy HBO “Liz was in court for a long time in 1977, where it was kind of broadly asserted by the prosecution that the car in and of itself was a sort of criminal scheme,” explained Drucker.

The trial actually lasted for over nine months, and Carmichael chose to represent herself.

“Ultimately, the car kind of becomes a surrogate for trans-ness, for the ways in which trans people are constantly called into question in the court of public opinion and constantly accused of fraud,” Drucker suggested.

Carmichael was eventually convicted, but she didn’t show up to sentencing, and her family went on the run again.

Authorities finally caught up with her over a decade later in Texas after her story appeared on an episode of TV’s “Unsolved Mysteries.”

Carmichael served an 18-month prison sentence for her crimes related to the Dale.

“After that 18 months, she went on and continued to put one foot in front of the other,” said Drucker. “Liz’s story to me is so inspiring because she is incredibly resilient and despite these incredible setbacks in life, she’s able to rebuild and take care of her family over and over again.”

After her release, Carmichael returned to Texas where she ran a flower business with her family. She died of cancer in 2004.

Reflecting on Carmichael’s life, Drucker continued, “I should mention, I’m a transgender woman myself, and I am a deep enthusiast of trans history. And I was also skeptical about Liz at first.”

So after digging in to Carmichael’s life, identity, and crimes, how does she feel about Carmichael?

“I feel like Liz’s story was so mired in the bias of the time, because that assertion that she was a man masquerading as a woman to commit a crime was so persistent,” Drucker said. “It erased her from even being a part of our history.”

“The story of Liz Carmichael and Dick Carlson is sort of a microcosm of what is today a debate that’s happening around the world,” Drucker said. “Fifty years ago, those conversations were in their inception and Liz was really thrown away like her story was exploited and then discarded.”

“Social justice movements take decades, centuries,” she said, “and we have a long way to go, but we’ve also come a long way.”

-

All About That Bass: Bruce Thomas On Playing With Elvis Costello

Elvis Costello emerged on the music scene as part of the punk/new wave music revolution that exploded during the mid-1970s. His backing band, The Attractions, was a huge part of Costello’s sound and his success.

Bassist Bruce Thomas, drummer Pete Thomas (no relation) and keyboard player Steve Nieve had the music chops and the propulsive energy to provide the perfect accompaniment no matter the genre — rock, soul and country — you name it.

Bruce Thomas is the author of a memoir called “Rough Notes: Dancing About Architecture.” In the book, Thomas reminisces about working with Paul McCartney and touring on Elton John’s private jet. And, of course, he revisits his time as a member of The Attractions.

In the late 1970s, Thomas spotted an advertisement in the popular British music magazine Melody Maker for a bass player for an unnamed musical artist. He had a pretty good idea of who the artist was.

“The London music scene wasn’t, like, huge,” Thomas told WPR’s “BETA.” “It was in the days of pop, rock and all that kind of thing. Pretty much everybody knew what was going on on the grapevine, as it were. So when the advert came out, I had an idea it was this guy Elvis Costello, making a few waves.”

Thomas said Costello didn’t want him to audition because Costello thought Thomas was too old school since Thomas had already been in bands and Costello was going for something new.

“When he asked who my favorite band was via the woman that answered the phone, I said, ‘Steely Dan,’ and I heard this voice at the other end saying, ‘Get rid of him, get rid of him,’ and the woman say, ‘No, he sounds OK,”’ Thomas recalled.

So Thomas bought the Costello records that were out at the time. He learned the songs and went to the audition in a South London rehearsal studio where he pretended he was hearing the songs for the first time. Even though the audition went well, Thomas thought Costello still wasn’t keen on him.

It was drummer Pete Thomas who convinced Costello that Bruce Thomas was the right guy to play bass. And Thomas ended up marrying the girl who answered the phone.

Thomas said the first time he played with his fellow Attractions, “it clicked straight away. It was pretty instant.”

The Attractions made their debut on Costello’s second album, “This Year’s Model,” which was released in March 1978. One of the standout tracks is “Pump It Up” featuring some very propulsive and frenetic bass playing from Thomas.

“In retrospect, a lot of the time, the riffs didn’t come from my fingers as much as from singing them, if you know what I mean,” Thomas explained. “It’s like if you would sing along, I didn’t realize I used to sing these parts until I heard myself on an isolated mic doing it. I used to often sing the parts as I was playing them because it helps you get the phrasing right.”

“When I analyzed it, it was actually a hybrid of a riff from (The) Everly Brothers song called ‘The Price of Love.’ But with the notes changed to those of a Richard Hell and the Voidoids track called ‘You Gotta Lose.’ And then there’s an odd bar where I played ‘You Really Got Me.’ It’s what I call organic sampling. You know, there’s nothing original, is there? But it’s how you put things together in a different combination, which is original.”

With so few riffs available, you could say Thomas was being environmentally responsible by recycling riffs.

“No single-use riffs here,” he laughed.

The first four albums Thomas and the other two Attractions recorded with Costello were all produced by Nick Lowe who is a bass player. Does Thomas think that’s one of the reasons his bass occupies so much bandwidth in the mixes?

“I used to think back in the day that I was getting a raw deal, you know, I was thinking, ‘Oh, the bass could be a bit louder,’” Thomas said.”But when I listen back to them now I think, ‘Crikey, they really pushed the bass front and center.’ I overplayed anyway. So I was quite happy to fill. And so I guess I filled the gaps in, and the bass seemed to carry quite a lot of the song structure.“

After the release of the “Armed Forces” album in 1979, Costello received some negative publicity for an incident that occurred at a hotel bar in Columbus, Ohio, where he got into a drunken argument with other musicians and he criticized Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley, Ray Charles and James Brown and used racial slurs. Costello apologized for his behavior at a press conference a couple of days later.

The next album for Costello and The Attractions was called “Get Happy!!” It featured 20 songs heavily influenced by Stax, Motown R&B and soul music. In his book, Thomas asks himself the question: “Were we subconsciously referencing all that was best in popular music as some kind of penance?”

“It would have been subconscious if it was. It wasn’t conscious,” Thomas said. “And some of the language used is very emotionally loaded and taboo now. And it certainly wasn’t that much at the time and not so much in England as it was in America, for instance.

Since the bass plays such a prominent part in soul and R&B, “Get Happy!!” serves as an excellent showcase for Thomas’ incredible bass skills.

“Well, that’s my album,” Thomas said of “Get Happy!!” “Steve Nieve hated it. He absolutely hated playing on that because it was nothing for him to do. Conversely, when we went and did the country album (“Almost Blue,” released in 1981), he was in his element doing all his trills and twiddles on the piano. And I might have been loping a horse with a wooden leg. Which is pretty much what all country bass parts sound like. Clip. Clop. Clip. Clip. Clip.”

“And it was the right album at the right time because I grew up on all that stuff on Stax and Motown and R&B,” Thomas continued. “That’s my favorite genre.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Brad Kolberg Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Mark Harris Guest

- Zackary Drucker Guest

- Bruce Thomas Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.