It didn’t take long after the 2010 election before Wisconsin found out what would happen to its share of the high-speed rail funding in the federal stimulus package.

During his campaign for governor, and even after he won, Scott Walker said he wanted to keep Wisconsin’s $810 million to spend on roads and bridges.

But that wouldn’t happen.

About a month after the election, the Obama administration made clear it would take back all but $2 million of Wisconsin’s money — redistributing it to other states.

The day it became official, Gov.-elect Walker told reporters Wisconsin had won.

“I think the fact that we don’t have a train between Milwaukee and Madison, and there’s no other way the federal government nor anyone else can force it is a victory,” he said.

Gov. Scott Walker talks about his legislative agenda in his office at the State Capitol in Madison, Wis on Jan. 19, 2011. Andy Manis/AP Photo

The money would be sent to other states almost immediately. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, New York, Illinois and Washington would all get pieces of it.

The biggest chunk — $624 million — would go to California, for a high-speed line linking San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Even in 2019, Walker is still taking a victory lap, saying difficulties with the California project vindicate his decision to block Wisconsin’s rail line.

It’s not a perfect comparison because Wisconsin’s rail line would have been a different kind of project. But California is where a majority of the money went.

A New Trajectory

California’s high-speed rail project predates Wisconsin’s train debate. The state had a referendum, proposition 1A, on the ballot in 2008. It passed the same night Barack Obama was elected president.

It authorized $9 billion in bonding for a high-speed rail line to connect San Francisco to Los Angeles in less than three hours. While that was more than the total high-speed rail funding in the federal stimulus package, it was never enough to fund the full project. In 2010, the project received an additional $2.34 billion from the federal stimulus.

While, Wisconsin’s rail project was what they called “shovel ready,” meaning the trains would have traveled along an existing rail corridor where land had already been purchased, California’s project essentially started from scratch. For miles and miles there was nothing there — no tracks, no rights of way.

When construction began, the state hadn’t acquired all of the land it needed, and land acquisition is currently ongoing. The process has delayed the project and driven the costs up significantly.

But the projects do share some similarities. Like Wisconsin, California’s rail project has been passed from governor to governor. It was once championed by Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Then, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown carried the torch. Now, the baton has been passed to Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, who was sworn in in January.

On the left, California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, inspects a China’s high-speed train at Hongqiao Railway Station in Shanghai, China, Sunday, Sept. 12, 2010. On the right, California Gov. Jerry Brown, center, displays signed legislation authorizing initial construction of California’s $68 billion high-speed rail line at Los Angeles’ Union Station Wednesday, July 18, 2012. Eugene Hoshiko and Damian Dovarganes/AP Photo

Newsom supports the rail line, but his position is complicated, because what he inherited was a rail project that was over budget and way behind schedule.

He addressed it almost immediately after he took office, in his first State of the State address. What he said would change the trajectory of the project

“Let’s be real,” Newsom said. “The current project, as planned, would cost too much and respectfully take too long. There’s been too little oversight and not enough transparency.”

This train was originally supposed to connect California’s two main population centers: the Bay Area and the southern coast. But Newsom said, at least for now, the state can’t do that.

“However, we do have the capacity to complete a high-speed rail link between Merced and Bakersfield,” he said.

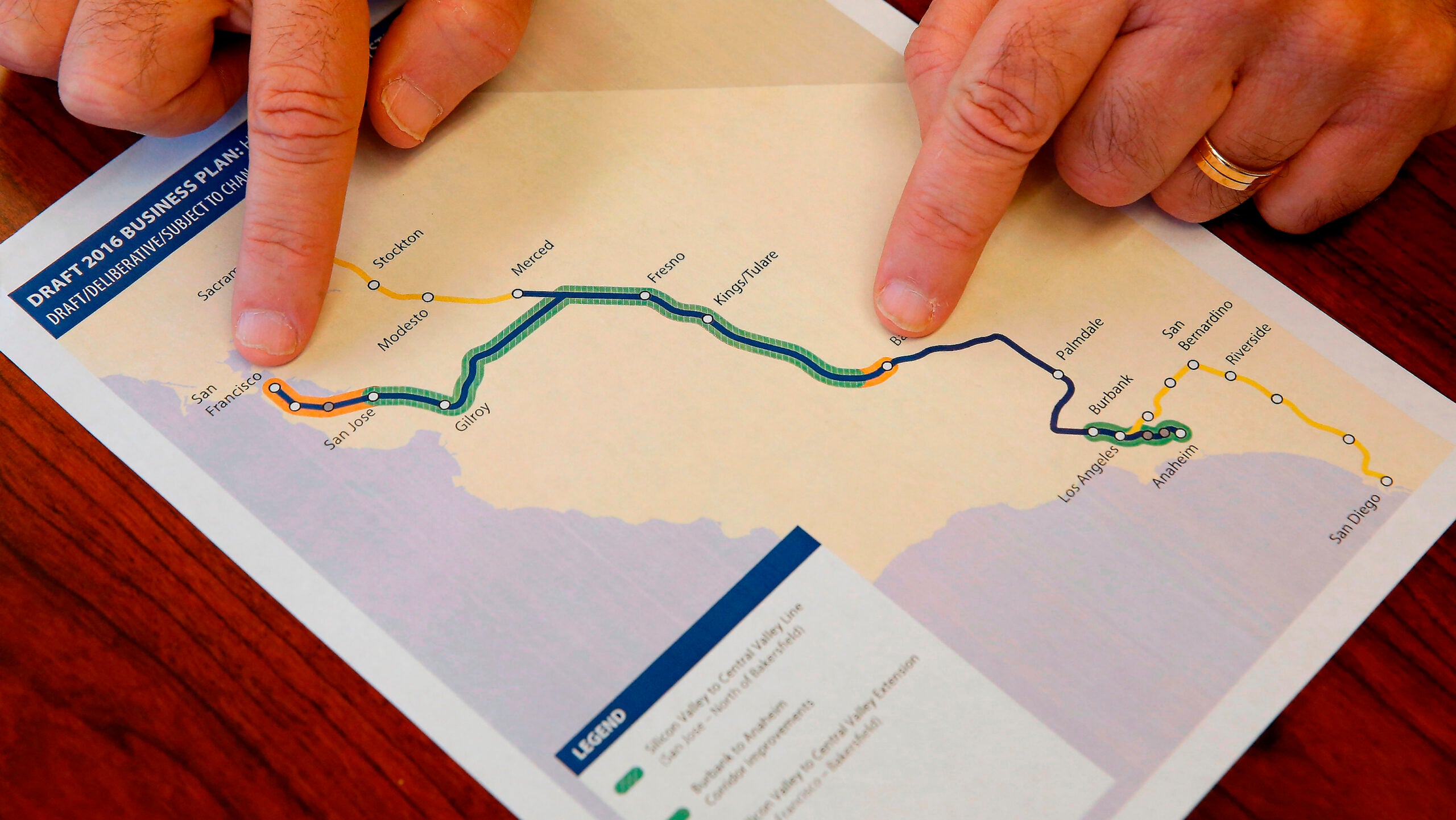

In this Feb. 18, 2016, photo, Dan Richard, chairman of the board that oversees the California High-Speed Rail Authority, points to a map showing the proposed initial construction of the bullet train in the revised business plan in Sacramento, Calif. Rich Pedroncelli/AP Photo

‘We Want Out’

E.J. Dejong’s dairy farm is in the heart of the Central Valley in Hanford, California.

It’s a large dairy, with about 5,000 cows.

On the property, not too far from Dejong’s house, there’s a big dirt path carving right through a field. That, Dejong said, is where the high-speed train will eventually run.

Dejong remembers when the high-speed rail proposal was on the ballot, but never imagined it would directly affect him. Eventually he got a letter in the mail — the official notification that the future train would run through his farm.

“It had a rough map on there, and our parcel numbers, and just basically warned us that it was coming,” he said. “Coming through our yard.”

The rail line will go through the epicenter of his farming operation. His main water and power lines will need to move. The train will come zooming through what is now his driveway, and just barely miss the corner of his house.

California’s high-speed rail line will go straight through E.J. Dejong’s dairy farm in Hanford, Calif. His main water and power lines will need to move. This photo shows land nearby Dejong’s farm where the high-speed rail line will also travel. Bridgit Bowden/WPR

“I tell my wife the good news is we don’t have to move,” Dejong said. “But she will want to … I think we can handle a little bit of dirt moving, but if they’re ever running a train that close to our house, we want out.”

When Dejong found out where the train would go, he also realized it would keep him from getting from one side of his farm to the other without driving all the way around on the main road.

He challenged this, and won. So, the rail authority agreed to build Dejong an underpass. But, even after a back-and-forth negotiation, the agreed-upon underpass wouldn’t be quite wide enough.

“That just means there’s one piece of equipment that won’t fit through,” Dejong said.

Dejong estimates that piece of equipment — a planter — costs about $55,000. But, the rail authority had a solution.

“They actually agreed to buy a planter for the other side,” he said.

‘The Most Frustrating Part’

Some people have argued that it’s time to throw in the towel with California’s high-speed rail project. But Gov. Newsom disagrees.

“Abandoning high-speed rail entirely means we will have wasted billions of dollars with nothing but broken promises, partially fulfilled commitments and lawsuits to show for it,” he said in his 2019 State of the State address.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom walks up the center aisle of the Assembly Chambers to deliver his first of the State of the State address to a joint session of the legislature at the Capitol Tuesday, Feb. 12, 2019, in Sacramento, Calif. Rich Pedroncelli/AP Photo

“And with all due respect, I have no interest in sending $3.5 billion in federal funding that was allocated to this project back to President Donald Trump.”

Trump took to Twitter the very next day to say he wanted the federal government’s money back. And months later, he followed through and took back $929 million.

In a speech to the National Association of Realtors in May, Trump belittled Newsom’s plan to prioritize the Central Valley section.

“Now you go from this tiny little town to another tiny little town, for billions of dollars, Trump said. “And they think they can do it for just billions of dollars more than the original projection. These people are crazy!”

This is huge for people like Dejong, whose land has already been taken to make way for the train. He just wants to get paid for what they’ve lost.

“Every time Trump tweets about it and threatens to take away more federal money, then I get a little more nervous,” Dejong said.

E.J. Dejong stands with some of the dairy cows that live on his 5,000 cattle dairy farm. California’s high-speed rail line will cut straight through his property, making the future of his operation uncertain. Bridgit Bowden/WPR

When Dejong first bought the property, he imagined he’d grow old there. But until the future of the train gets resolved, he’s not sure what to do.

“The uncertainty is probably the most frustrating part,” he said.

‘The Future Is Not Coming’

About 45 minutes from Dejong’s farm is the city of Fresno. It’s the fifth largest city in California, by population, a little smaller than Milwaukee but a lot bigger than Madison.

Much of the construction for the high-speed rail line is happening there. But even though several large rail construction projects are underway, many residents aren’t clear on whether or not the high-speed rail project is still happening.

According to California High Speed Rail Authority spokesperson Toni Tinoco, it absolutely is.

“There have been some reports in the news of funding,” she said. “But as far as construction in the Valley, nothing has changed. We’re still moving forward.”

There’s a huge benefit to taking the rail line through the Central Valley, Tinoco said, insisting that it wasn’t just meant to be a fast connection between San Francisco and LA. It was always meant to connect the Central Valley to the state’s biggest cities, she said, to make Fresno and other places bedroom communities of the Bay Area, where housing is tight.

“In order for people to work, live out in the Bay Area, go to school there, commute back, things like that,” Tinoco said.

But construction in Fresno is taking a long time. They broke ground in 2015, and since then, a lot of roads have been closed. For businesses in Fresno’s Chinatown neighborhood, that has meant trouble. Chinatown has been separated from busy downtown Fresno by the high-speed rail construction area.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.