Should former Gov. Jim Doyle have moved ahead with the high-speed train when he was a lame duck?

Will Madison ever have passenger rail?

Also, what did the 2016 Olympics have to do with all of this?

Because the story of “Derailed” happened over the course of decades, there’s a lot there, and a lot we didn’t get to.

Some of it, like Doyle’s role in ending the train, is still discussed today. Other stuff, like the Olympics connection, seems to have been lost to history.

Here are some of the questions we didn’t get to in “Derailed.”

Did Gov. Jim Doyle Kill The Train?

There’s a key detail in the high-speed rail saga that sometimes gets overlooked: It wasn’t technically former Gov. Scott Walker who halted this project. It was former Gov. Jim Doyle.

Doyle paused work on the rail line two days after Walker was elected in 2010, and it never started back up again.

There are obvious reasons this is a footnote to the larger story of the train.

For one, Walker ran against this train in a very public way.

And key decision-makers point the finger at Walker. Ray LaHood, former President Barack Obama’s Transportation Secretary, said, without a doubt, it was Walker who stopped the train. LaHood told WPR he tried to get Walker to change his mind after the election, but the governor-elect wouldn’t budge.

But other people who wanted this rail project vividly remember Doyle’s role in the decision. And some blame Doyle for not fighting harder.

On a Saturday morning at the Dane County Farmers’ Market in Madison in late September, Diane and Tim Osswald had a lot to say about Doyle.

“He understood where the incoming government stood on it, and he backed off,” said Diane Osswald. “And he shouldn’t have.”

“Doyle really needs to be blamed for it,” said Tim Osswald. “He was still the governor. So he basically, then, was handing in the keys to the house a few days before the lease was signed. You don’t do that.”

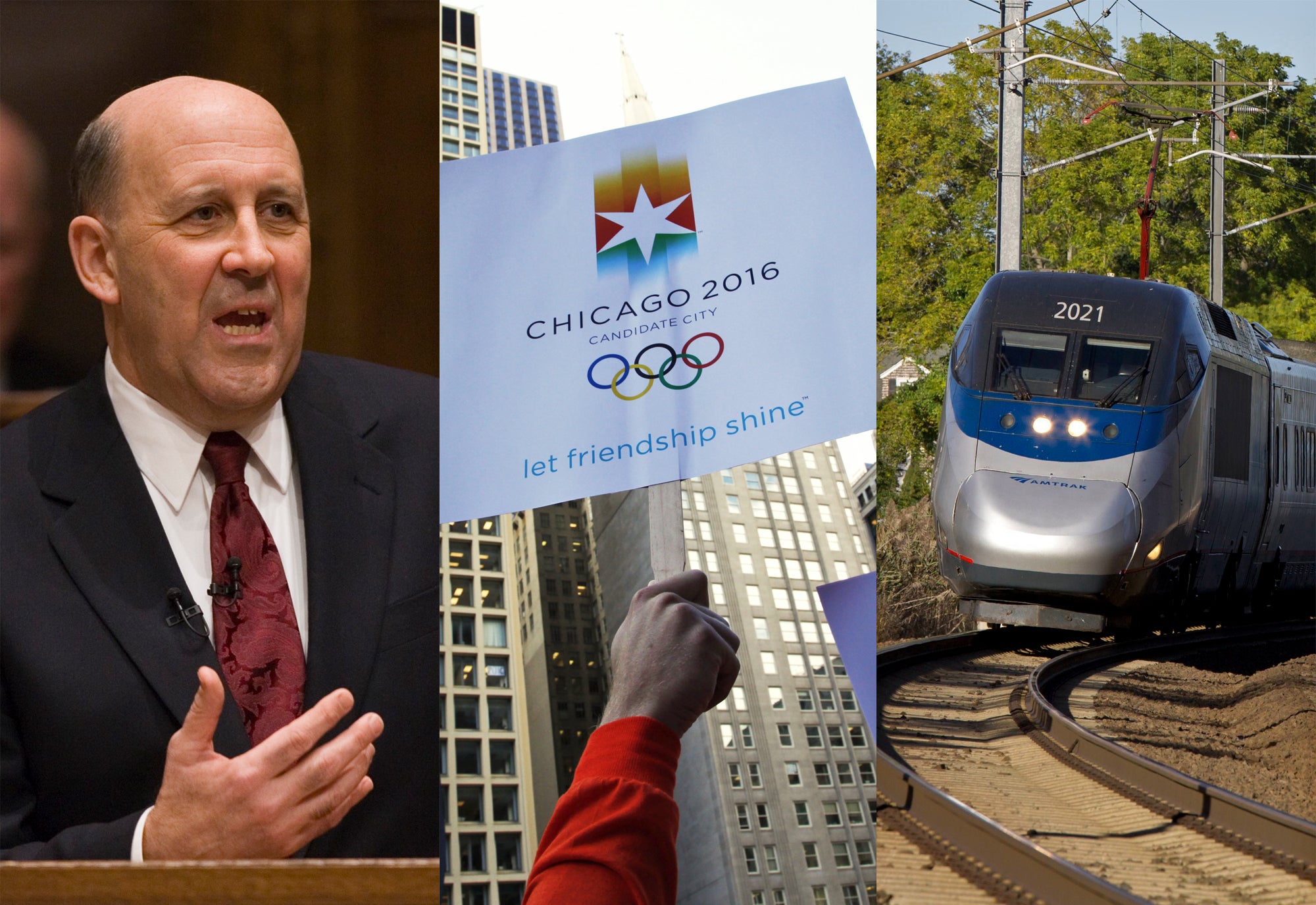

Gov. Jim Doyle talks with reporters after the voting at Midvale Elementary School in Madison, Wis., Tuesday, Nov. 7, 2006. Andy Manis/AP Photo Photo

Walker was elected on Nov. 2, 2010, but Doyle was still governor, and he would still be running state government for another two months. Some Democrats thought he should have run it more aggressively.

Spencer Black, the Democratic state representative from Madison who put $50 million in rail bonding in the budget in 1993, was still a state representative in 2010. He wanted Doyle to move forward with the rail line, even after Walker’s election.

“Oh, I thought at the time — it’s not even hindsight — I mean right at the time I thought, you know, you should just get this done,” Black told WPR.

Doyle isn’t unaware of this sentiment, but he said he doesn’t feel like he ever had a choice.

“Does anybody really think I didn’t want this train?” Doyle told WPR. “I mean I, more than anybody in this whole story, I’m the one that brought this train here. I would have loved to have had this train.”

Doyle said the rail project was still in the early stages in November 2010 because the U.S. Department of Transportation wasn’t moving as quickly as he’d hoped. Even if he kept the project moving temporarily, he didn’t think it was fair to workers who would be laid off once Walker took office in January.

“There was no way in the world you could say to somebody, ‘Go to work on something that you’re going to have to quit working on in 30 days.’ So that’s the reality of where we were,” Doyle said.

Doyle was willing to take other political risks at the end of his governorship, pushing unsuccessfully to renew state employee contracts. Those contracts never passed the Democratic-controlled state Senate in 2010.

All of this is viewed in a different light today because of the way Walker used his last months in office as a lame-duck governor.

While Doyle chose not to go to the mat for the train in 2010, Walker was far more aggressive when he was a lame duck in 2018.

After Walker lost the 2018 election, Republican lawmakers moved quickly to pass laws that would limit the power of his Democratic successor, Tony Evers. And Walker supported it.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, addresses the press ahead of the Assembly gathering for an extraordinary lame-duck session of the Legislature held Dec. 4 and 5, 2018, at the Wisconsin state Capitol in Madison, Wis. Coburn Dukehart/Wisconsin Watch

“The will of the voters four years ago was to elect me to a term that ends Jan. 7,” Walker said in December 2018. “And so I don’t stop. Even though the media treats an election as though that’s the end of the term, it’s not.”

Given the way Walker handled his last days in office, some Democrats think Doyle should have been more aggressive with the train.

Others think Doyle did the right thing. Dan Schoof, who was running Doyle’s state Department of Administration during his last months in office, said what Doyle did was honorable.

“Is Gov. Doyle not vindictive and partisan? No, he’s not,” Schoof said. “We’ll let history judge those eight years versus his eight years, you know? But I think yeah, this partisan jamming of things wasn’t his thing and ultimately probably isn’t good for the state.”

Did The 2016 Olympics Influence Wisconsin’s Train Debate?

Sometimes, when you’re working on a story like this, it takes you somewhere you didn’t expect to go.

For us, it’s the 2016 Summer Olympics.

That may sound completely out of the blue, but it’s an idea that stuck with us — one that we tried to chase all the way to the top.

The story starts with Chicago, which was one of four finalists for the 2016 Summer Games.

Chicago 2016 supporters hold up placards while waiting in Daley Square for the announcement from the 121st International Olympic Committee on the host city for the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Chicago, Friday, Oct. 2, 2009. Morry Gash/AP Photo

Chicago’s plan for the games included a cycling course in a neighboring state: Wisconsin. The course would be held in the rolling hills outside of Madison.

This was something Doyle would allude to from time to time when he was discussing the train, including at the 2009 press conference where he announced Wisconsin’s deal with Talgo.

“Imagine being able to get on a high speed train in Chicago for all those Olympic visitors and to be able to come and see the biking events here in Madison,” Doyle said at the announcement.

He was using Chicago’s Olympic bid to promote a new passenger rail line to Madison, and it wasn’t just an aside. Doyle met with the International Olympic Committee in 2009, and spoke to reporters after the meeting.

“There was quite a bit of discussion I had with individual members of the (International Olympic Committee),” Doyle said. “And they were very interested in the potential of really high quality, high-speed passenger rail connecting Chicago with Madison.”

Part of the reason this stuck with us is that we were trying to figure out why the high speed rail funding in the 2009 federal stimulus bill grew by so much so fast.

When the stimulus bill first passed the U.S. House of Representatives, there was no money set aside for high-speed rail, and by the time it was signed into law, there was $8 billion.

A similar thing happened in Wisconsin. At first, the state was just looking to upgrade the Chicago to Milwaukee Hiawatha rail line. By the end it was asking for the full amount to extend the line to Madison. And it got it. Every single dime.

As we tracked the process of the stimulus bill, we realized all the rail funding got added at the last minute. And this is what really grabbed our attention.

Because who was involved in that last step of the process for the stimulus bill? The White House. Then-President Barack Obama.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.