Born in February of 1897 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, famed African American opera singer Marian Anderson, grew up humbly. Her father was an ice and coal dealer. Her mother worked as a laundress. Together, they provided only a meager income to support three daughters, one of which would go on to become one of the world’s greatest contraltos.

Growing up poor, Marian Anderson, nor her sisters thought of themselves as such. A newly acquired piano, crumbling but functional in the parlor affirmed the view that their lives had been richly rewarded with a instrument unaware that it would become the primer for a future career in opera for young Marian.

For many African Americans during the early post-enslavement years in the U.S., the Black church served to not only to save souls, it sustained a large disenfranchised segment of America, and in doing so became a school of fine arts where many talented members trained and performed. Anderson was no exception, singing in her hometown choir at Union Baptist Church. Marian’s beautiful voice and ability to read and interpret a vocal score paved the way for recurrent invitations to render Sunday morning solos.

Later while in high school Anderson attempted to enroll at a local music school. Her application was returned with the assigned words, “We don’t accept Colored”. However, Yale University did accept her, though a lack of money kept her from applying. Along the way, a host of voice teachers and coaches including Amanda Aldridge (daughter of famed Shakesperean actor Ira Aldridge). Collectively, they provided her with the pedagogical tools required for life as a professional artist. Yet, it was her ethnicity that proved to be the biggest life long challenge to her quest to perform on the stages of opera houses in the United States.

By 1921 Marian Anderson was a well-established and highly celebrated artist abroad and within the African American Church community. Still, her mysterious ability to sing in a range assigned typically to baritones, coupled with the racial prejudice of the period, caused deep fear among Opera House Directors and befuddled most opera critics at home.

Among Marian Anderson’s many significant ground-breaking and door-opening performances, awards and recognition, are three exceptional episodes – her 1939 Lincoln Memorial performance (Daughters of the American Revolution had denied Anderson permission to sing in Constitution Hall, Washington, D.C.), her 1955, long overdue, history-making debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York and, her singing of the National Anthem at the inauguration of U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1957.

Tk 14 “My Lord, What a Morning”, Marian Anderson, 3:27, Sprituals, BMG, 1999 (originally recorded May 6, 1947, New York City, Trad. Arr. By Harry T. Burleigh, Franz Rupp, Pianist.

This is another in a series exploring music the world over and its power to create greater understanding of those near and far.

Episode Credits

- Dr. Jonathan Øverby Producer

- Joe Hardtke Technical Director

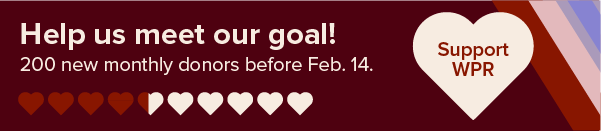

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.