How the Cuban revolution eventually led to 15K refugees in Wisconsin

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 2: traducción al español

It’s the 1950s. The president of Cuba is Fulgencio Batista — known as “El Hombre.”

Batista took full control of the country through a coup in the early 50s. He had backing from the United States and favored foreign investment. U.S companies owned a huge percentage of Cuba’s sugar cane fields, mines and utilities. Batista eventually invested in public infrastructure and gambling operations.

There was also corruption and embezzlement. And the gap between rich and poor citizens was growing.

While people in cities were generally comfortable, their fellow Cubans in rural areas were starving. Batista’s secret police tortured and killed his political opponents.

By the end of 1958, Batista was losing on the battlefield to rebels known as el Movimiento 26 de Julio, or 26th of July Movement. He was also losing popular support in Cuba and the backing from the U.S. government.

Early in the morning on Jan. 1, 1959, Batista got on a plane with some of his allies and aides — and millions of dollars — and fled the country.

After years of running Cuba, El Hombre was gone.

Ricardo Gonzalez has a story about that day. He was 12 years old.

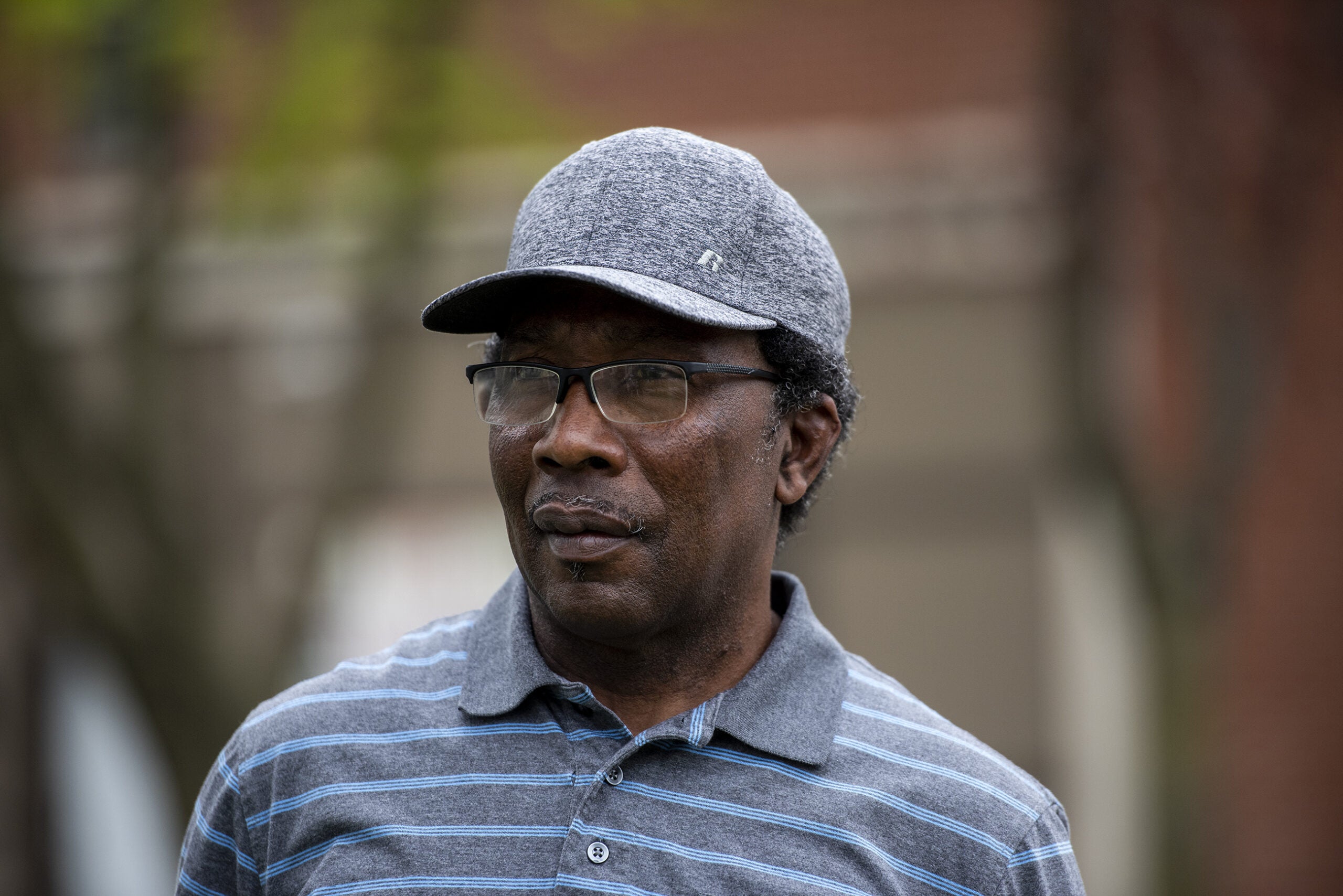

Gonzalez grew up in Camagüey, Cuba. He’s a longtime Madison resident who once served on the city’s Common Council.

Back in 1959, he was an altar boy at the chapel down the street from his home.

“Jan. 1 is a day of precept in the Catholic Church, meaning that day you go to mass. And so I had to go down to the chapel and set up for the mass for that day,” Gonzalez said. “As I was leaving my house, I ran into the el sereno, which is like the nightwatchman of the neighborhood, who happened to be standing right in front of our house.

“As I came out, he said to me, ‘Se cayo Batista’ — Batista has fallen. And I immediately knew what that was about, even though I didn’t know much about the news or anything like that.”

Gonzalez ran to the chapel and started ringing the church bells nonstop, so much so that the rope broke. He said the whole neighborhood woke to the news and started talking about what happened.

“And the next thing,” Gonzalez said, “I outfitted my bike with a flag of Cuba and a flag of the 26th of July Movement, which I made myself. I went around the neighborhood celebrating the triumph of the revolution.”

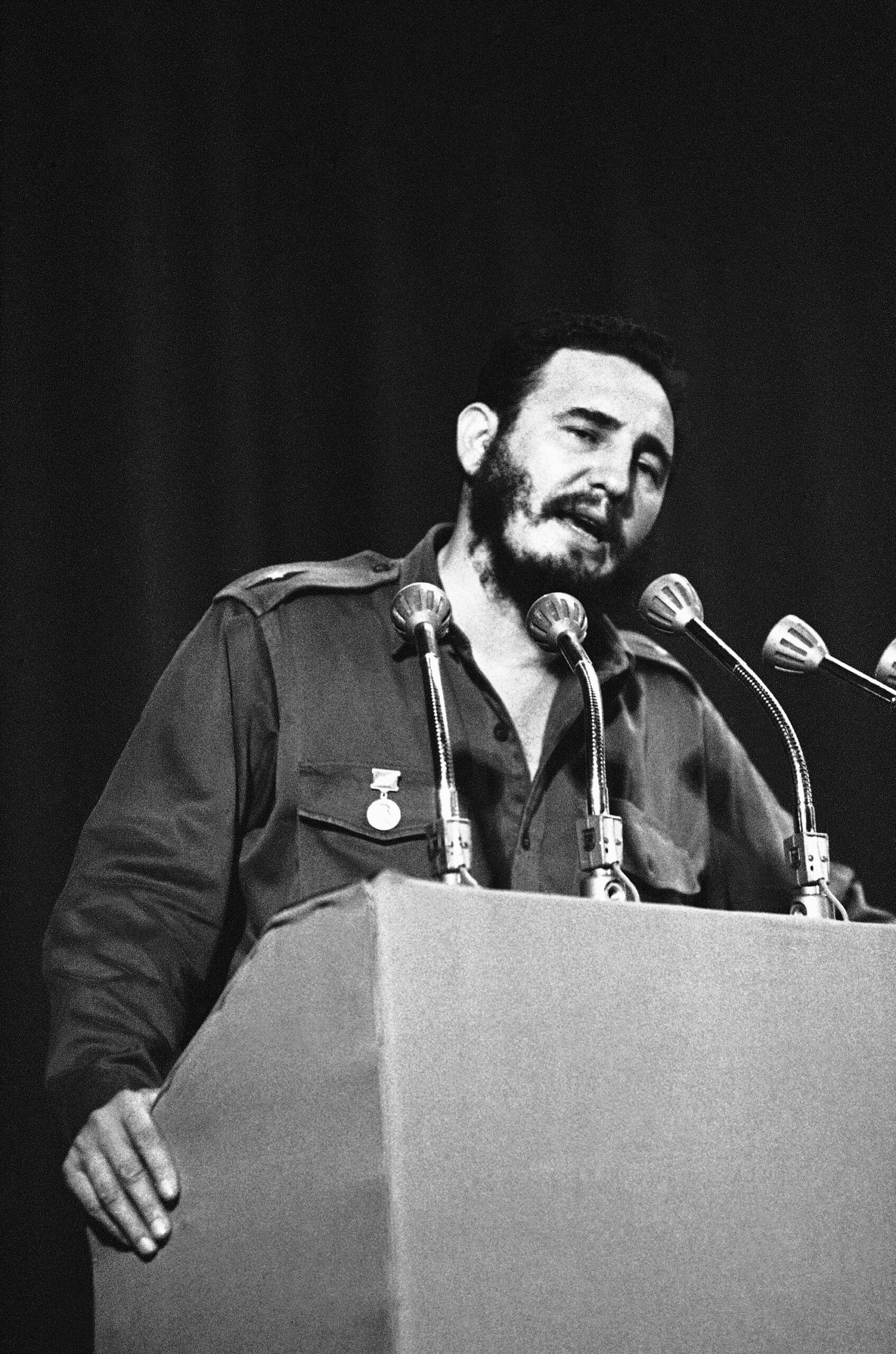

The leader of that revolution and the government that followed was a young Fidel Castro: the man who would go on to become el Comandante, the prime minister and president of Cuba.

Castro and his revolution were everywhere. And it changed everyone’s lives.

Castro promised a revolutionary utopia. But Omar Granados, an associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted,” said getting there meant sacrifice.

Some, including many wealthy Cubans, feared the shift to communism and left the country almost right away — like Gonzalez’s family, who came to the U.S. in 1960.

Decades later, the changes brought on by the revolution would also lead to almost 15,000 Cuban refugees coming to Wisconsin as part of the Mariel Boatlift of 1980.

The Mariel Boatlift was a major public demonstration against the revolutionary government of Castro, Granados said. What the Mariel Boatlift showed, in a way, was the beginning of the end of Castro’s revolutionary utopia, Granados added.

The shift to communism in Cuba after the revolution eventually provided free health care, education and subsidized housing to its citizens. The government also started regulating and running businesses, redistributing land and controlling the media.

Citizens had been living as capitalists for decades. All of a sudden, Granados said, there was a traumatic shift in every part of life.

Growing up in communist Cuba

One young person affected by the revolution was Ernesto Rodriguez, who now lives in La Crosse.

When Rodriguez was 10 years old living in Camagüey Province, he and his friends would skip school. He was more into history and geography, so when it was time for math class, he’d take off and go to the river with his friends. Rodriguez and his friends would have handstand races. And money was on the line.

“The one who gets to the river first, (gets) all the money,” Rodriguez said. “I win like three times. First time, I win like $7. The last time, I won $12 because all the kids wanted to do it. And you can get the girl.”

He was just a kid at the time, getting the attention of girls and bringing in big bucks by winning handstand races in revolutionary Cuba. But whether 10-year-old Rodriguez knew it or not, the revolution was heavily impacting his life.

Lillian Guerra is a professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida. She is an author and has written extensively on Cuba, Puerto Rico and Latin America. She has lived in Cuba and received her doctorate in history from UW-Madison.

She said the revolution seeped into every aspect of life.

“The result is that you have a really intense, kind of a flourishing of the state in your life and in every nook and cranny of your identity, especially if you’re a young person. So the state begins to be a part of your life in a way that’s inescapable,” Guerra said “In the 60s, you were increasingly called to show that you were a patriot.

“You were supposed to be a member of the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution. You’re supposed to do guard duty at night or during the day. You’re supposed to give blood. You’re supposed to do voluntary labor either through your school or your workplace. You’re supposed to be a member of the various organizations that touch on your identity.”

The expectations and goals kept evolving, which was apparent for young people in school. They had to give up their own dreams for the common project. And in the 1970s, that pressure grew.

“Now, 1973, suddenly the goal of the school system becomes to develop a communist personality in every child with precise and specific content,” Guerra explained. “And so that meant not only that you had a real intensification and policing of thought in schools, but you also had schools that divorced you, that pulled you away from your parents deliberately so that you wouldn’t have a bourgeois mentality or any legacy of that that could contaminate your ideological commitment to the revolution and to communism.”

Granados said the revolution sold itself as a transformational thing, but was limiting.

“You can’t learn about music, the hippie movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Beatles,” he said. “Those things were a contradiction with the revolution.”

And by the late 70s, Guerra said, came a generation fed up with this control.

“They also have very few choices about what they’re going to do, how they’re going to dress, what kind of music they can listen to, who they can hang out with, who they can love, and all of that is constantly reinforced and policed,” she said.

“You’re supposed to do guard duty at night or during the day. You’re supposed to give blood.”

Lillian Guerra

Race in Cuba

Outside the classroom, other changes from the revolution were taking hold — like a shift in racial dynamics.

Guerra said early in the revolution, Castro’s administration did something that very publicly addressed race: They desegregated the beaches and made them public in 1959.

“That means that white racist people who had never had to hang out with Black people were doing so. And some people really found — especially young people really found — this to be the marker, the hallmark of change,” Guerra said.

Along with beaches, the government desegregated places like schools, yacht clubs and businesses. As a result, race became a key factor in how Cubans perceived the quality of change.

The country was dealing with race, but people weren’t really allowed to talk about it openly, Granados said. He said those were the colorblind policies of the Cuban revolution — assuming everyone was equal.

These policies are part of the reason some Black Cubans became disenchanted, Guerra added.

“You destroy all of the Black social clubs and Black societies that had really been the pinnacle of Black empowerment for more than a century. You get rid of all those things because … the government should control civil society and be the owner, really, of all the organizations that comprise it,” Guerra said. “So by 1961, when Fidel Castro officially embraces socialism and communism, and communism rises to becoming Communist Party, (becoming) a primary player in the state — when all that happens, suddenly race and discussing race becomes taboo.”

In February 1962, Castro gave a six-hour long speech, referred to as “The Second Declaration of Havana,” in which he declares the revolution has defeated racism.

But some Black Cubans didn’t agree.

“When you ask the question, ‘Why did young Black people in the 1970s want to get the hell out of Cuba?’ One of the major reasons is that between 1962 and 1980, Black young people — that included communist members of the party, youth revolutionaries, filmmakers, people who identified with the revolution — they want to talk about how it’s not just class that drives racism,” Guerra said. “They want to talk about all that, and it is taboo, and they get themselves in trouble.”

By this, Guerra explained, some leaders of this young, Black revolutionary society were censored, some were electroshocked at the National Insane Asylum and some were put into forced labor camps.

Influence from La Escuela al Campo and the military

The revolution saw youth as the backbone of its production force. That means people had to give up their individuality to produce for the revolution and contribute to a communist society, Granados said.

“You have to be part of a working force that is thinking about developing the country,” he said. “Now, in the 1970s, the revolution is still young and inexperienced.”

There were a number of programs that were implemented into the lives of young people, including a political commitment to the revolution, and participation in La Escuela al Campo, or “School in the Countryside.”

As early as 1966, La Escuela al Campo had become a major part of Cuban educational policy, and all urban junior high school students were expected to spend time in rural Cuba.

This was mostly to educate youth on the love for Cuba and the value of labor. And more specifically, to teach them how to remove the differences or disparities between urban and rural communities in order to establish more links between school life and work life — to educate a generation of children that would eventually work for the revolutionary project, Granados explained.

At La Escuela al Campo, teenagers had to pick tobacco, fruits and vegetables. Granados said youth lived at an agricultural production facility for 45 days. They were separated from their families. They were also discovering their sexuality and drinking alcohol.

“They had no idea how to use a machete or what’s best for any crops, so it’s definitely bad for production,” Granado said.

But the Cuban government also saw La Escuela al Campo as an educational experience that would show young Cubans the importance of labor, community and social commitment.

Another experience that has an impact on the lives of Cuban teenagers — then and now — is obligatory military service. Boys had to serve the government in some way, including time with the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

“Military preparation is something that you do from the time you were a child. You pick up guns, they may be unloaded, but you learn how to use them,” Guerra said.

“The Ministry of the (Revolutionary) Armed Forces had a special program where they actually embedded different members of local bases into schools. They were called ‘the padrinos’ — ‘the godfathers’ – of these schools,” Guerra continued. “So the kids, from the time that they’re in first, second, third grade forward, would have direct contact with members of the military, (they) would not question military service.”

Serving in the Cuban military in the 1970s was a big deal. The threat of the U.S. invading Cuba in the 1970s was far more of a reality than it is today. And the economic needs of the country in the 70s were much more demanding, which means the militarybecame a workforce.

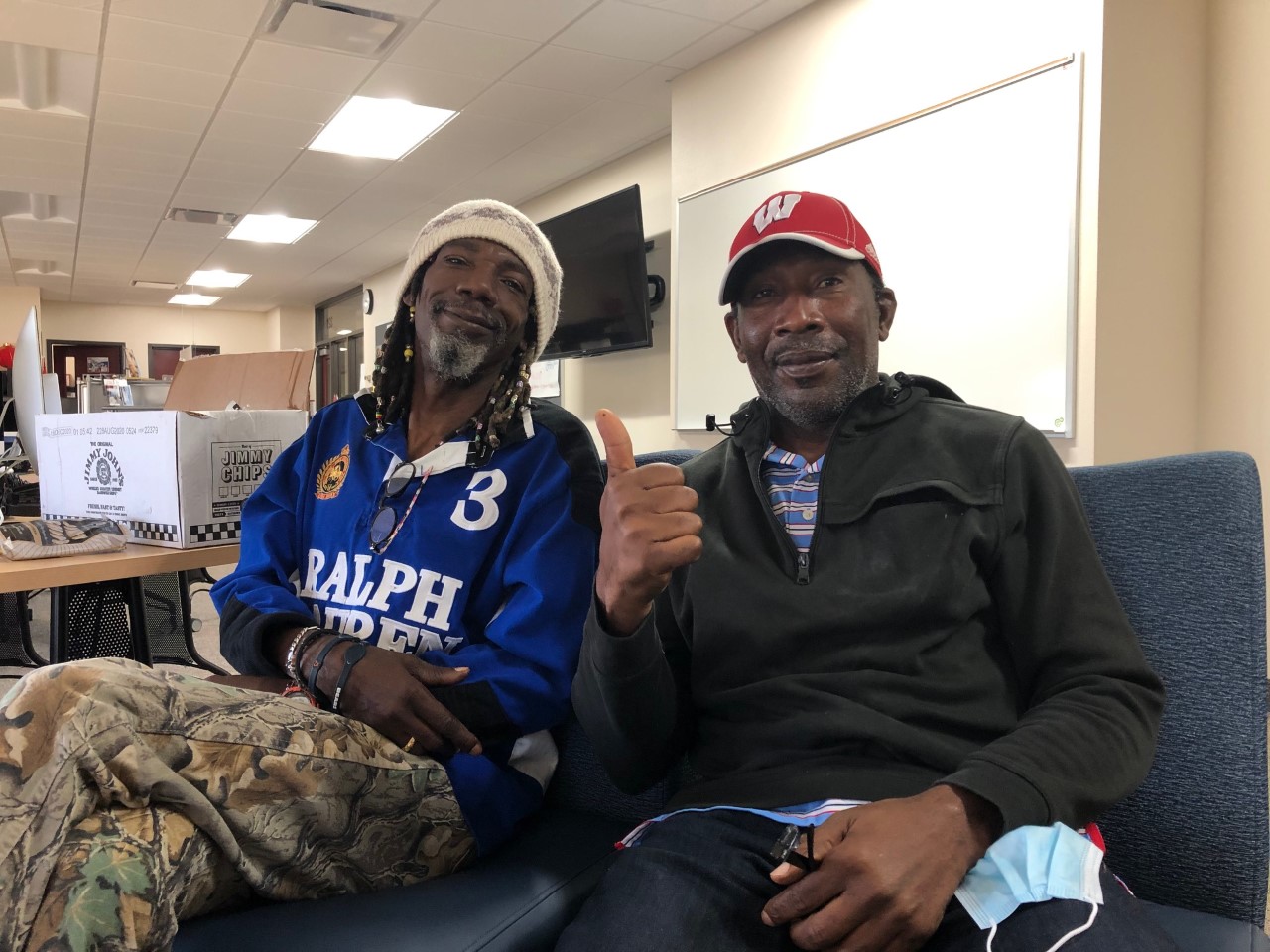

Rodosvaldo Pozo served in the Cuban Revolutionary Army.

He currently lives with Rodriguez in La Crosse.Not only are they roommates, they’re practically brothers. They both grew up in Cuba’s Camagüey Province, but didn’t meet until their late teens.

“But I was kind of a little mischievous, you know,” Pozo said. “Like Lady Gaga says: she born this way.”

Despite his mischief, Pozo was a smart student. He comes from a big family in Florida, Cuba, with 11 brothers and sisters. His dad was a band conductor and his mom took care of the house.

Pozo’s parents got divorced when he was a teenager.

“Even though my mama marry somebody else, they all used to get along with each other,” Pozo said. “Their mutual respect and love. You know … that’s the one thing that my family taught me: To love and be kind.”

Once Pozo became a teenager, he joined the Cuban Army. But he wasn’t psyched about being in the military, and he wasn’t a fan of the country’s communist leadership.

When he was a teenager in the 1970s, an officer accused Pozo of sabotaging sugar cane fields with a molotov cocktail. As part of his military service, this was a crop he was supposed to protect.

Pozo was sentenced to 26 years in Cuban prison for this. Much of that time was spent in solitary confinement.

“I was in prison when I came here (Wisconsin) because I don’t agree with the government. I was in the army, and I was doing a lot of stuff … they are accusing me of (doing) sabotage against the government,” Pozo said.

Pozo wouldn’t say whether or not he did it: “Well I don’t like the Cuban government. So I plead the fifth.”

Burning sugar cane fields in Cuba carried a heavy sentence because the Cuban government traded sugar with the Soviet Union in exchange for, well, everything, Granados said.

Rodriguez also had to cut sugar cane for 10 hours a day in the 1970s as part of his teenage military service. Then it was classes for four hours and in bed with lights out at 10 p.m. sharp. If you were caught talking, you were written up.

But Rodriguez ended up being disciplined for something else while in the military, something the Army thought was far worse than talking to his friends after lights out.

When he was 18 years old, inCamagüey, his father died on the opposite end of the island, in Havana. Rodriguez had to miss the funeral.

“They don’t give me a pass to go to see my father until my father was buried,” Rodriguez said. “Three or like four days later, I went to La Havana. Then, when I get over there, they showed me where my father was buried.”

Once Rodriguez was in Havana, he only had five days off to mourn. Then he had to turn around and get back to his military unit. But the government hadn’t given him enough money to cover the return trip. He could only afford to take the bus part way.

If he didn’t make it back in time, Rodriguez would be disciplined. Not to mention, he was extremely hungry.

“And when I get off, I mean, I have no money, no nothing,” he said. “I started walking, and I see a bike. I look everywhere, I see nobody. I go, ‘Well, I can get the bike and go to where I have to, and then I can send back the bike or leave it over there.’”

But right before he was out of the city on the bike, Rodriguez saw sirens.

Police pulled Rodriguez over. They sent him to the Kilo 7 prison.

“After 11 months I was there,” Rodriguez said. “I told the people … ‘Look I only steal, I don’t kill nobody. I only stole the bike because I wanted to go to my unit and I don’t want to get in trouble.’ I got in trouble.”

Rodriguez said a judge let him go after 11 months. He said his time in prison was scary because he was surrounded by a lot of “bad people” and murderers.

Pozo was also at Kilo 7 at that time, serving his sentence for the alleged sugar cane incident. This is where the two friends first met.

Their punishments may seem severe, but they aligned with the Cuban government’s wishes for a crime-free society, Granados said.

‘Alienation and exhaustion’

Guerra said that attitude toward crime disproportionately affected Black Cubans.

“In this landscape of social dangerousness, Black people are targeted more than whites because there is a longstanding belief in Cuba that Blacks are natural criminals,” she said. “And so in the … late 60s through the 70s, you have work camps and schools that are set up to deal with what the Cuban government calls ‘pre-delinquents,’ who turn out to be 80 percent Black. They’re little kids — 12, 13, 14 — who have high absentee rates from school.”

Guerra said many of the families who were targeted lived in marginal communities and didn’t always want the state telling them what they could and couldn’t do.

“Whether they can be selling something or not selling somethin. Whether they can make cheese or ham in their house. Whether they can worship the saint they want to worship,” Guerra said.

“And the state’s intrusion into the lives of slum dwellers, former slum dwellers, most of whom are Black, then turns. And so the culture itself and the context itself is one that creates a dynamic of push factors and alienation and exhaustion from all of this by 1980,” she continued.

That alienation and exhaustion was real for people such as Rodriguez and Pozo.

Despite all the government’s promises, people were left trying to survive, to provide for their families. Find food. Get money. Some had seen family members leave for the U.S. and they wanted to reunite. People wanted to travel and see the world, but they couldn’t leave the country.

Some Cubans were tired of the expectation that society had to serve the revolution. They were beginning to realize the revolution was not for them — and they had to get out.

In the next episode of “Uprooted”: Pressure builds and Cubans find a way out through the walls of an embassy in April 1980. This leads to Ernesto Rodriguez and Rodosvaldo Pozo finally getting out of prison and to the Port of Mariel.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

0

0

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.