Mariel refugees find their way in the Midwest

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 6: traducción al español próximamente

On a warm, sunny afternoon in April 2021 along the lake at Brittingham Park in Madison, people gathered under a shelter decorated with balloons and Cuban flags.

Tables were packed to the edges with black beans and rice, plantains and shredded pork. Family and friends sat closely in circles, talking with one another.

Musicians pulled out guitars and congas and started jamming as others hit the dance floor. Armando Rodriguez, Rodosvaldo Pozo, Osvaldo Durruthy and Ernesto Rodriguez were all there.

They were celebrating the life of Jesus Cisneros-Hernandez, an avid chess player and beloved family man. He moved to the United States from Cuba with his father in 1981, a year after the Mariel Boatlift. He eventually settled down in Madison.

Cubans from across Wisconsin traveled to the park to remember Cisneros-Hernandez, who was 71 years old when he died from prostate cancer, and to support his wife, children and grandchildren.

This group makes up a younger generation of multiracial Wisconsinites who embrace their Cuban heritage. They took pictures with the Cuban elders and the giant Cuban flags.

There were also non-Cubans here — native Wisconsinites whose lives were marked by the experience of the Cuban exodus to the state, like Brian Brandstetter, who’s from Sparta.

Brandstetter met Ernesto Rodriguez, who goes by Erne, in a kitchen at Fort McCoy, where many Cubans lived in the summer and fall of 1980 after arriving in the U.S. as part of the Mariel Boatlift.

The Mariel refugees could not get out of Fort McCoy without a family member or sponsor vouching for them because they were classified under a new immigration designation: the Cuban Haitian Entrant Program. About 15,000 people at Fort McCoy needed to find family members or sponsors.

Sponsors provided the refugees with food, shelter and clothing. They also assisted refugees with navigating American systems, like filling out documents for green cards and work permits.

Erne’s journey to the U.S. wasn’t easy. Eventually, though, he found a family to not only sponsor him, but to love and care for him. And they helped him start a new life in Wisconsin.

Erne and the Brandsetters

After leaving Fort McCoy, Erne moved in with the Brandstetter family, who sponsored him.

“Erne is my brother from another mother,” Brian Brandstetter said, smiling.

Erne added: “We are good friends. We are good brothers because I love the guy like it’s my own brother.”

“I’ve been your brother longer than not,” Brian replied.

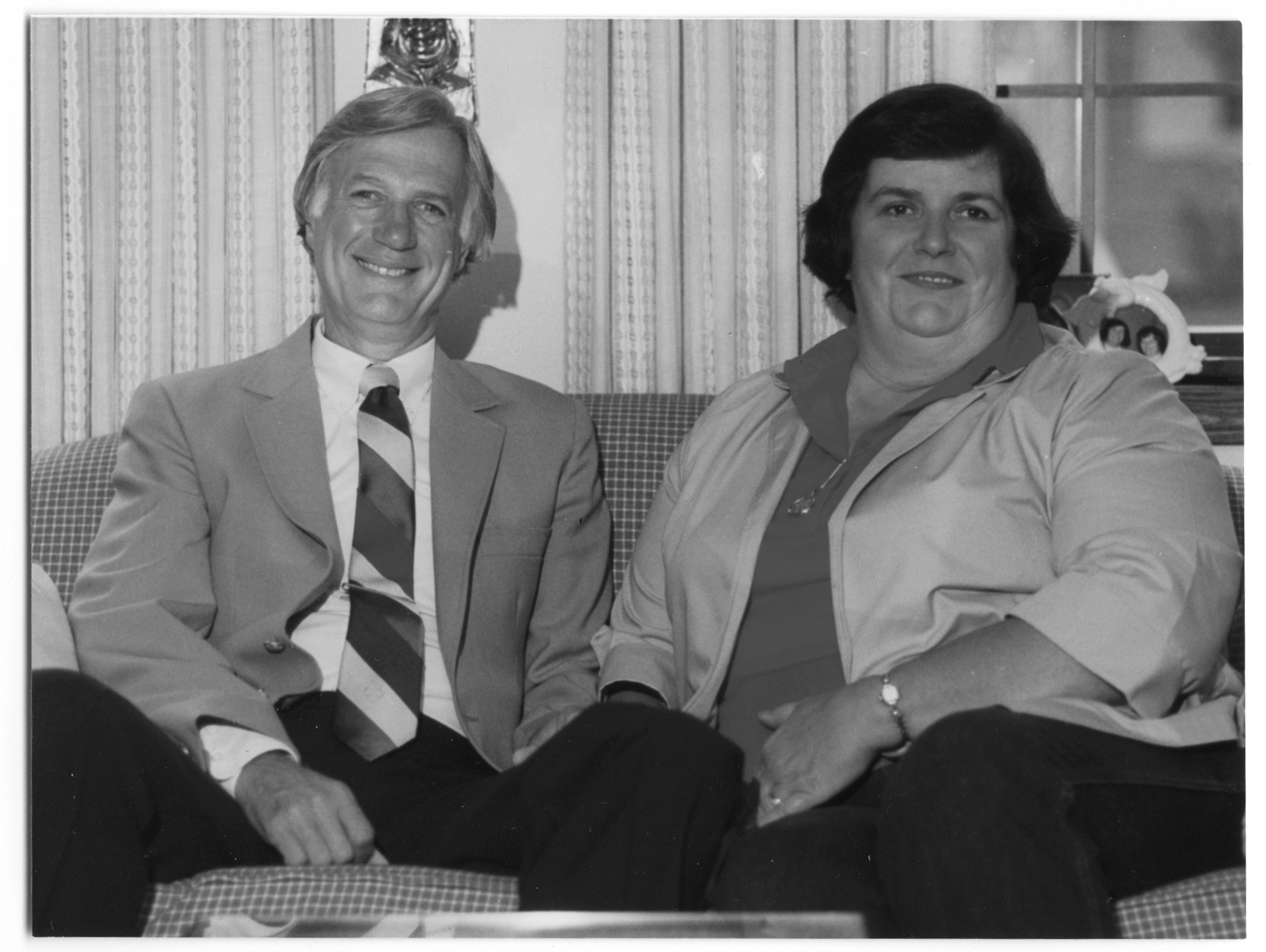

Annette and Roger Brandstetter, Brian’s mother and father, became Erne’s sponsors in the fall of 1980 when he was 24 years old.

Brian, who was 20 years old in 1980, said he’d share clothes with Erne, and Annette and Roger shopped for things Erne needed.

The family loved each other.

“She was the best mom … I never had a mom,” Erne said.

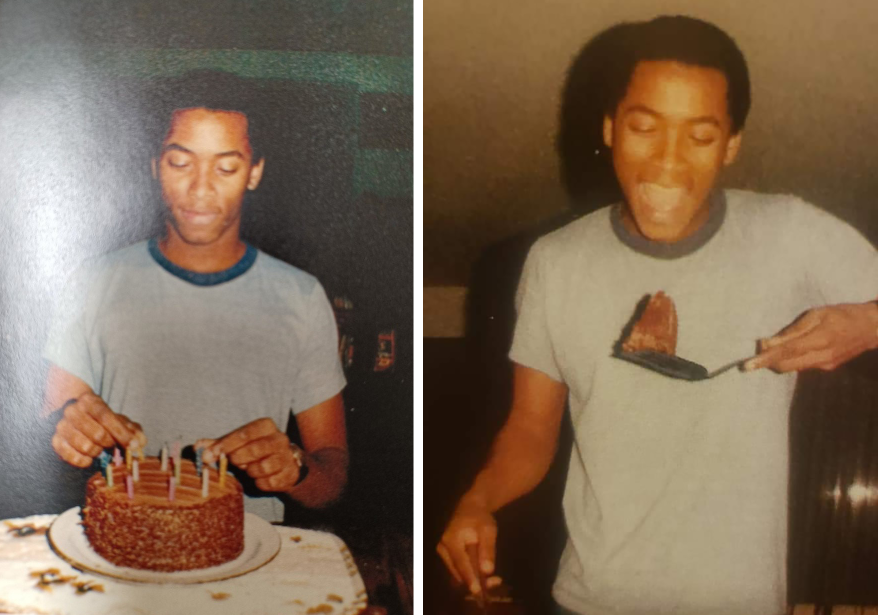

Every year for his birthday, Annette would call Erne and tell him to come pick up his gifts: money and a pineapple upside-down cake. Even though Erne refused the gifts, Annette kept them coming, even at Christmas.

“I’m lucky, I’m super lucky,” Erne said, “because they give me everything. I don’t need nothing. They give me everything.”

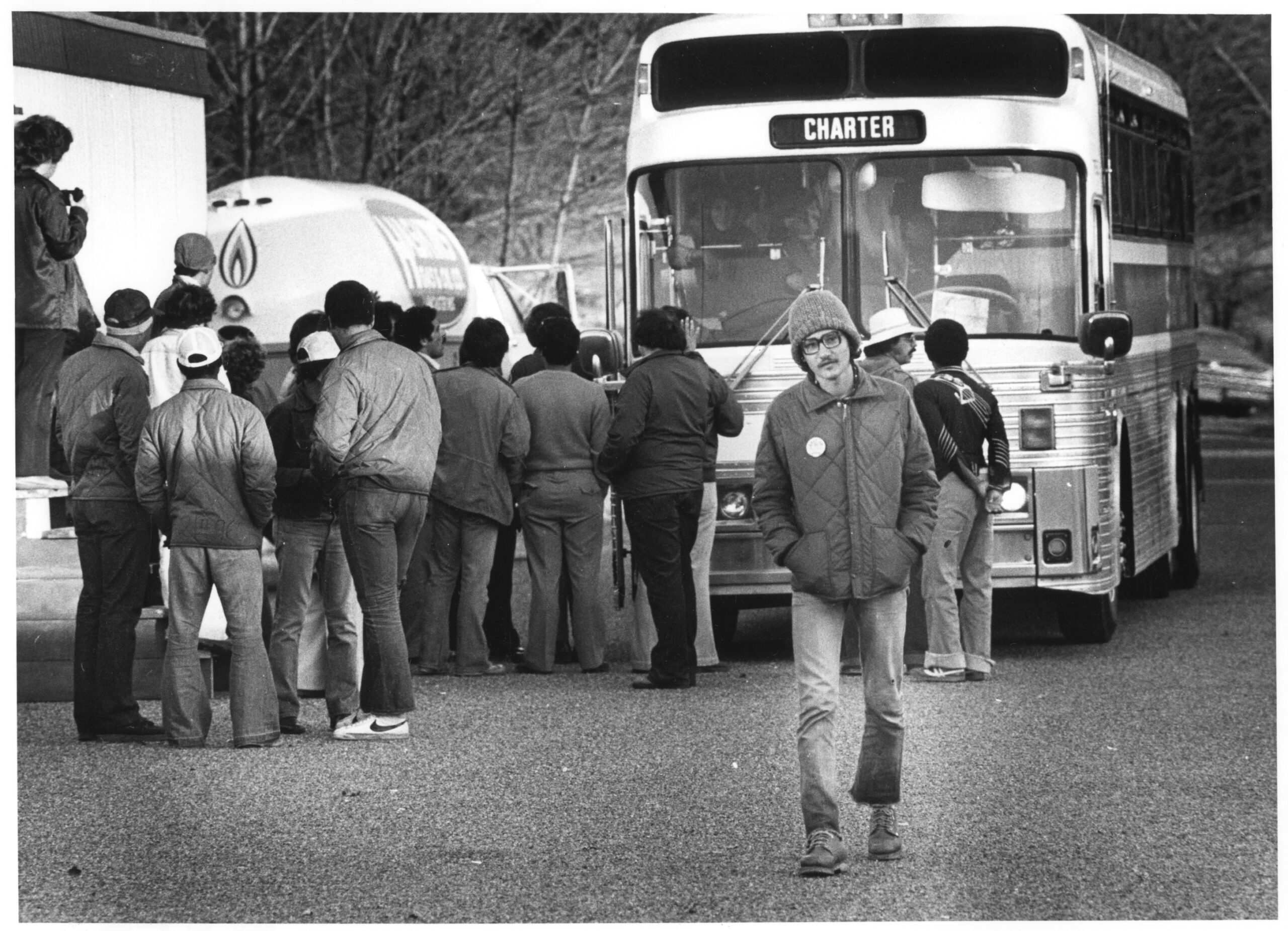

Brian was working as a cook at Fort McCoy in the summer of 1980. He was studying hotel restaurant management at the University of Wisconsin-Stout.

He said working in the barracks and interacting with thousands of Cubans was a culture shock for him.

“We (Fort McCoy staff) were there before the Cubans, so we had a week of getting ready and familiarize ourselves,” Brian said. “It was weird because … I’m from little Sparta, Wisconsin. And you’ll see all of these guys that speak a different language. And everyone’s sort of freaked out.”

“And then the brain trust at Fort McCoy thought, ‘Oh, we’ll just make them hamburgers and hot dogs.’ And they’re like, ‘What is this crap?’” Brian continued.

Some of the cooks, like Brian, started asking what type of food the Cuban refugees preferred. They learned to make dishes like congri, chicken fricassee and mashed potatoes.

It was that time together in the kitchens at Fort McCoy where Erne bonded with Brian and his brother, Joe.

Eventually, the brothers encouraged their parents to sponsor Cuban refugees at Fort McCoy.

“It (was) like, ‘We got to get them out of there. They’re too good of guys. They’re going to go to Fort Chaffee. They’re gonna get put in the system. Some of them might even go back to jail,’” Brian explained. “So my parents, having a big heart, (opened) their door. And my dad had a very optimistic view. He goes, ‘Oh, we’ll teach them English, we’ll get them in the church, we’ll get them working.’”

Erne actually had a sponsor before the Brandsetters. He and one of his friends moved in with a couple in Sparta and lived there for a month.

But Erne said the sponsor’s girlfriend didn’t want Black Cubans living in their home. So they left, with nowhere to go but back to Fort McCoy.

Erne and his friend were walking down Main Street in Sparta, on their way back to the camp, when they saw Annette driving by. Erne told her about the conflict with his sponsor as she sat in the driver’s seat of her car.

“She said, ‘You guys are not going to Fort McCoy … Get in the car,’” Erne recalled.

In the end, the Brandstetters officially sponsored four Cuban refugees and let another one live with them, all men. The guys helped around the house and in the garden. And they were happy to have a new home.

The story of the Brandstetters and Erne is a perfect example of racial solidarity inside and outside Fort McCoy, said Omar Granados, associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at UW-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.” Despite the image of the Mariel refugees in the press and stories about racism in the communities, internally at Fort McCoy, Black Cubans and white Americans were getting along and sharing their cultures.

Because the Brandstetters’ relationships were strong with the people they sponsored, it helped Erne and the others adjust to a new life in Sparta.

The refugees staying with the Brandstetters were able to get jobs. Roger hired them to work at his car dealership, Sparta Motors. This was a big deal, since it was not always easy for Cubans to find jobs because of racism and stereotypes that Mariel refugees were criminals.

It was also significant because this was one of the first times the Cuban refugees had money in their pockets, said Granados. They were raised under communism and now had to understand capitalism. Getting a job and learning how to use money made the transition to the U.S. easier, he added.

“I’m lucky, I’m super lucky, because they give me everything. I don’t need nothing. They give me everything.”

Erne Rodriguez

Roger also helped Erne get his green card — something sponsors were supposed to do.

But not all sponsors helped the refugees adjust to life in the U.S., which left many refugees in limbo after leaving Fort McCoy.

Some sponsors just didn’t understand how to navigate the legal and immigration systems, Granados said. They didn’t know what paperwork the refugees needed to fill out and received little direction from the federal government. There was also a language barrier.

Some sponsors were only in it for their own benefit, Granados added. Sponsors received up to $1,000 to help pay for food and clothes. Some collected checks for themselves, weren’t supportive or kicked the refugees out of their homes quickly. In some instances, farmers and other businesses forced refugees to do cheap labor.

And there were families and refugees who just didn’t click. Other times, some refugees took advantage of their sponsors or didn’t understand the new culture.

But the Brandstetters became sponsors for the benefit of people like Erne, not for themselves. And actually, welcoming the Mariel refugees to their majority-white community cost them.

“They tried to take the Cubans to church and the looks they’d get … If you know that area of the state, back in 1980, it’s less educated, a lot more redneck,” Brian said.

“My parents lost a lot of their right-leaning friends because they’re like, ‘How could you do this? You let them into your house. You let them work for you,’” he continued, adding that his mother was stern and would get defensive — in turn, she made a few enemies.

Brian found this difficult as he tried to balance high school friendships and his brotherly connection with the Cubans his family sponsored. He was often caught in the middle when there were fights between Sparta natives and Cuban exiles at the bars.

Brian said Erne has taught him a lot in life. Not just how to cook or how to say some swear words in Spanish, but how to be more open-minded. Erne’s optimistic spirit also taught Brian how to keep things light, he said.

For Erne, he gained another family.

“I had to love that family because nobody do this for a Black guy in another country,” Erne said.

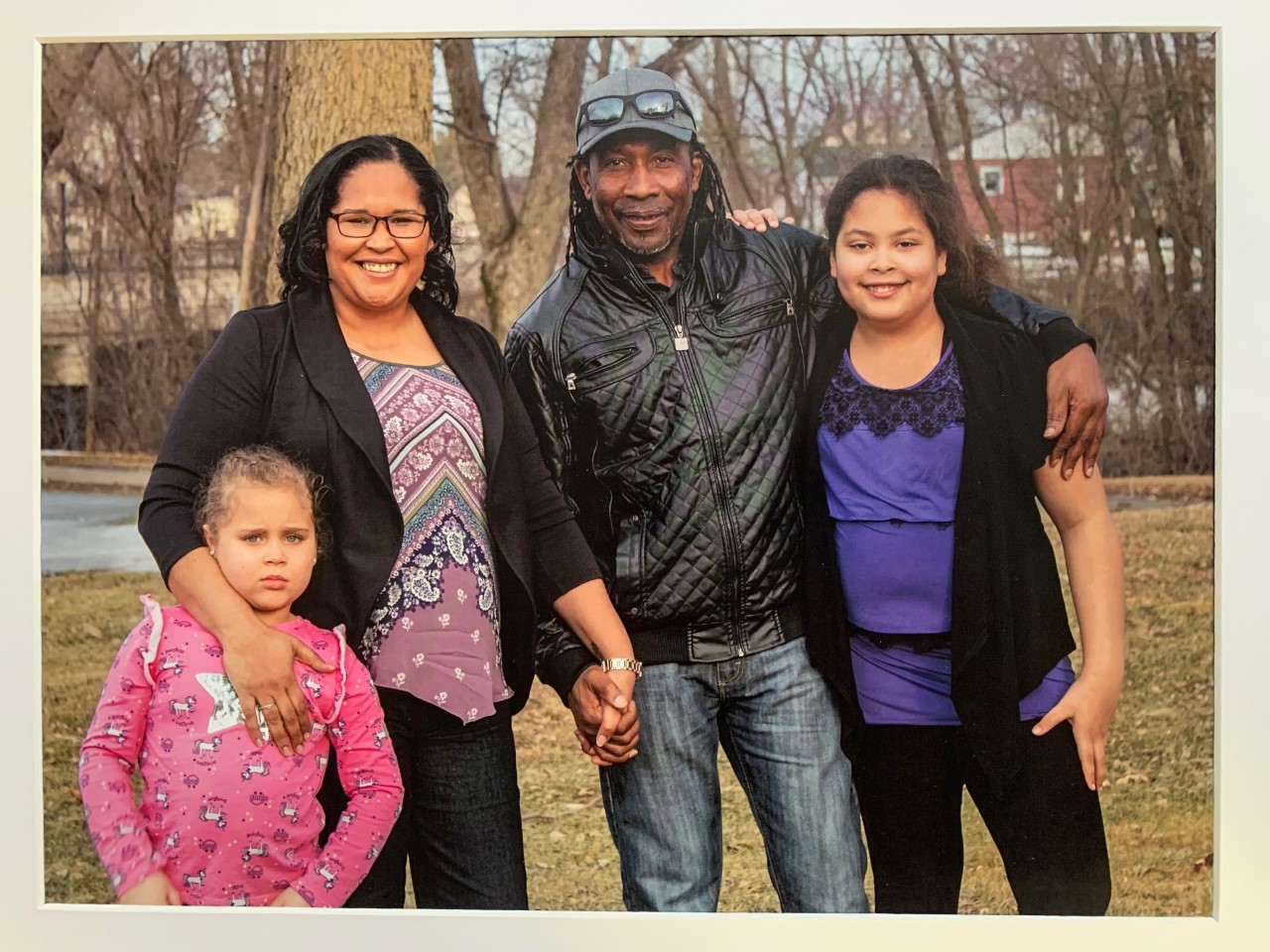

And unlike most Mariel refugees who came through Fort McCoy, Rodriguez didn’t settle down in Florida or move to a big city. He has lived in the Upper Midwest for the last four decades. He’s worked at the Hormel Foods plant in Austin, Minnesota. In La Crosse, he’s worked in the food industry and as a handyman.

He also started his own family. Erne has three children — two girls and a boy. And he’s a grandfather. He calls his granddaughter “his princess.”

Ricardo Gonzalez and the Cuban Salsa Band

People who sponsored Cuban refugees out of Fort McCoy weren’t just limited to southwest Wisconsin. They were also in cities like Milwaukee and Madison.

Ricardo Gonzalez is a longtime Madison Common Council member and business owner.

Gonzalez’s family left Cuba in the 1960s following the revolution. He eventually ended up in Wisconsin for a job. Gonzalez fell in love with Madison, where he opened the iconic Cardinal Bar and Rick’s Havana Club.

While the Mariel Boatlift was underway in 1980, Gonzalez was executive director of the Madison-based Spanish American Organization. When refugees were sent to Wisconsin, Gonzalez set off to Fort McCoy to help his fellow Cubans find sponsors.

“When we got there, and I saw all these Cuban(s), mostly men, just hanging around with nothing — when I saw that, I hurt, personally. I felt hurt that so many of my countrymen were in that situation. And I thought, ‘This is not right that this is happening, and what are we going to do about it?’” Gonzalez said.

But Gonzalez couldn’t sponsor everyone at Fort McCoy. He and his organization decidedto focus on sponsoring families. They also sponsored the small number of single women at Fort McCoy, as well as people in the LGBTQ+ community.

“Because I thought a lot of people were thrown in jail in Cuba for being homosexual. A new law had just been approved in Cuba a couple of years earlier called la ley de la peligrosidad — the law of dangerousness. People might be thrown in jail for being gay. Well, that to us was not a criminal offense,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez and the Spanish American Organization found sponsors around Madison for the refugees, though he says most of them left Wisconsin pretty quickly.

When Gonzalez was making those regular visits to Fort McCoy throughout the summer, he caught wind that a group of musicians had formed a band. Since he owned dance clubs and loved music, it gave him an idea.

“We loaned them some instruments and they played a benefit show in Madison. Then they had to go back to Fort McCoy. That’s when I decided to get them organized as a band and sponsor them as a group. And that’s what we did. We sponsored all 12 of them,” Gonzalez said.

This group of 12 musicians became known as the Cuban Salsa Band. Gonzalez rented an apartment for them in downtown Madison. A local church paid for new instruments and a sound system for the band.

“I gave them a speech about how music is the language that breaks down the barriers. (It’s an) international language. You don’t have to speak it. You just listen to it, you feel it. And in that concept is what I thought the Cuban musicians of the Cuban Salsa Band would help generate, goodwill towards the refugees,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez thought once people got to know the musicians, maybe they’d want to sponsor other Cuban refugees. But it was getting harder to convince people to become sponsors as time went on.

The refugees were navigating a new culture with new systems and rules. Some didn’t know how to pay rent or find jobs, which sometimes resulted in criminal behavior, at least by U.S. standards, said Granados.

“Some people were dealing drugs and getting in fights. They don’t know the full extent of the law in the United States. They may think a fight is just a fight and may not realize the impact it has on people like Ricardo (Gonzalez), a bar owner,” explained Granados.

“As the Cubans adapt to life in the U.S., Ricardo (Gonzalez) is trying to help people settle with the best intentions, but these guys grew up in a completely different Cuba than Ricardo remembers. This was a cultural clash even for him,” Granados continued.

Gonzalez started distancing himself from the refugees. He thought some of them were taking advantage of him and hurting his business at the Cardinal Bar.

His relationship with the Cuban Salsa Band deteriorated over time. They played shows all over Madison and across the Upper Midwest in 1980 and 1981, but after a year, the Cuban Salsa Band broke up.

Gonzalez said he’s still in touch with some of the musicians. One had a successful music career in Chicago. Others stayed in Madison. Some ended up in prison, others involved in the drug trade.

Gonzalez and his organization could only connect a few dozen refugees with sponsors in Madison. And families, like the Brandstetters in Sparta who sponsored Ernesto Rodriguez, could only help a few Cuban refugees on their own.

“I felt hurt that so many of my countrymen were in that situation. I thought this is not right that this is happening, and what are we going to do about it?”

Ricardo Gonzalez

Religious sponsors

The majority of Cuban refugees were sponsored out of Fort McCoy through religious organizations. The United States Catholic Conference of Bishops, formerly the United States Catholic Conference, helped place the majority of Fort McCoy’s refugees with sponsors, with one report saying it helped settle 60 percent of the Mariel refugees, or about 9,000 people.

Lutheran and Jewish organizations also placed some of the refugees with sponsors, as did secular organizations. Religious organizations still take the lead on many refugee resettlements in Wisconsin today.

But these placements didn’t always work out.

Some refugees at Fort McCoy were Catholic, but people couldn’t openly practice religion in Cuba. They had been taught to be wary of religion. So being placed with a religious family at times caused issues.

Lillian Guerra, author and professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida, said not only were people taught to be skeptical of religion, but many had little knowledge of it.

“Those who attended schools in the 60s or the 70s had been taught that the Catholic Church might be filled with counterrevolutionaries,” Guerra said. “But Protestants were demonized in sort of very empty ways where there really wasn’t any understanding of what their faith was. And so Cubans who would have arrived in 1980, who were then sent to Protestant homes with the often very, very religious people — people who would pray around the table, who would take the refugees to church … who didn’t speak Spanish or spoke a kind of missionary Spanish — I mean, all they were succeeding in doing was sort of hyper-traumatizing the refugee who didn’t know how to behave.”

This caused some refugees to leave their sponsors, Guerra added.

“When I’ve interviewed Marielitos (Mariel refugees), you get the sense that they are products of a highly surveilled society in which national security is part of the culture and that hanging out in a church or going to a prayer group is considered some kind of ideological treason. So the experience of communism itself really just demobilizes and demoralizes the Marielitos. Then, the experience of having been embraced ostensibly by religious people… It was a disaster,” Guerra said.

The minors at Wyalusing State Park

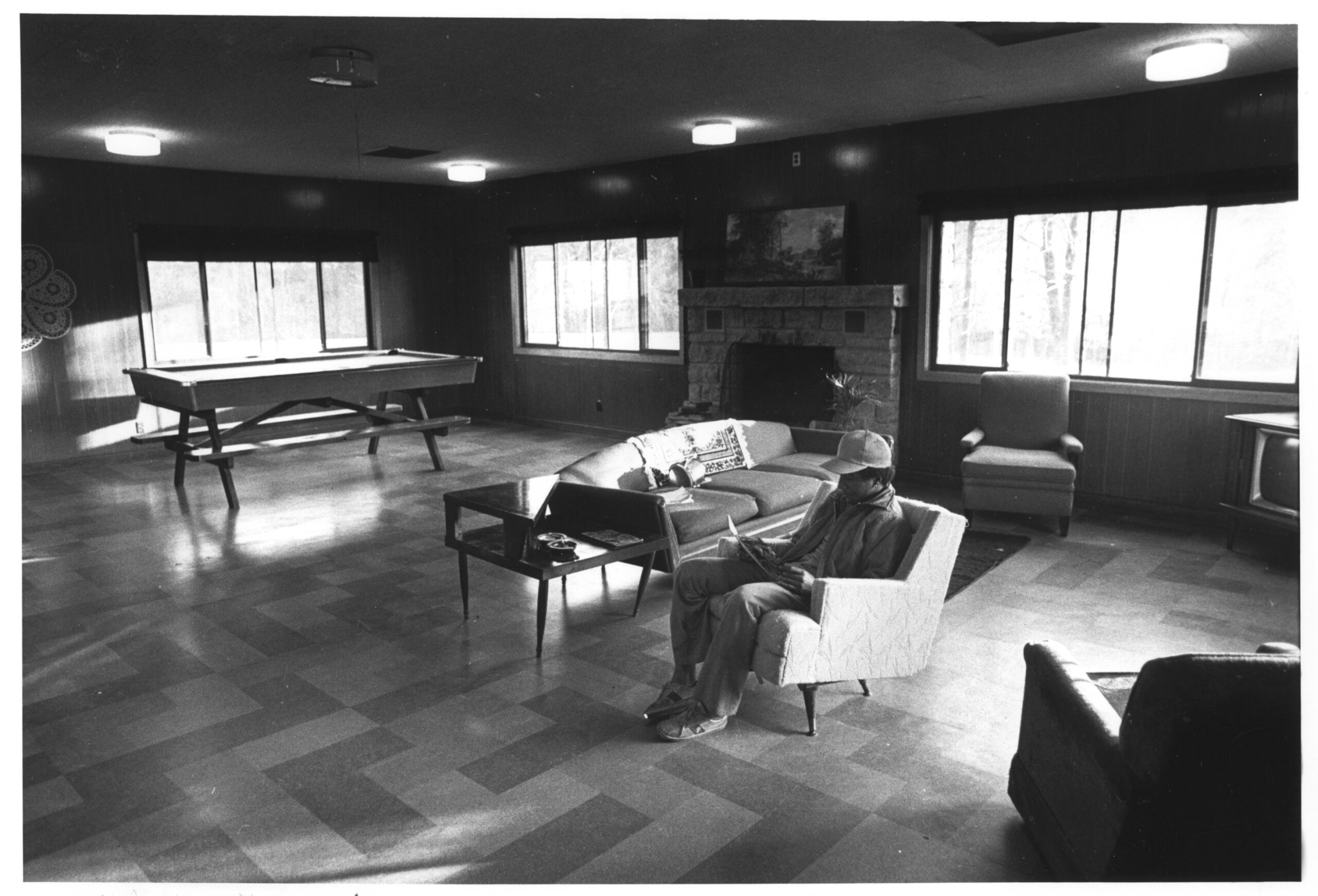

The unaccompanied teenagers living at Fort McCoy became the legal and financial responsibility of the state in September 1980, through the Wisconsin Department of Health and Social Services. This happened around the same time that U.S. District Court Federal Judge Barbara Crabb in Madison ruled extra protections be placed on the juveniles at Fort McCoy who “had been subjected to physical abuse, sexual attack, and physical restraint.” She also placed parameters on their movements inside and outside the camp until they found family or sponsors.

But by the time the camp closed in November 1980, around 90 unaccompanied minors still did not have sponsors.

They were sent to live at Wyalusing State Park near Prairie du Chien — a gorgeous part of the state, where the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers meet.

Among those sent there was Armando Rodriguez, who now lives in Madison.

“I liked it a lot (at Wyalusing State Park) because I was free. And I felt happy,” he said. “I was going fishing. And little by little, English got to me a little bit. I never got in trouble there.”

The teens could stretch out once they got to Wyalusing, breathe a sigh of relief. Some had experienced abuse at Fort McCoy, and there was hope they would be more protected at Wyalusing State Park.

John Satory is an art gallery owner in La Crosse. After working in the dental clinic at Fort McCoy in 1980, he went to work with the minors at Wyalusing, along with dozens of Fort McCoy staff. They organized activities, classes and even field trips, like roller-skating at High Rollers in La Crosse.

While at Wyalusing, Armando met someone who changed his life.

“There was an American, white American, who loved us very much and we loved him very much. He would take us fishing and walking around,” he said. “And I asked the American if he could be my dad one day. He looked me in the eye and didn’t answer me. That same night he called me with an interpreter and he told me that yes, that he was going to take me home.”

Armando left Wyalusing and moved into his new home with Dennis and Nancy Maloney in Madison on Dec. 13, 1980. It was his 18th birthday.

Armando lived with his sponsors for about 2.5 years. He said they were his best years in the U.S.

“I was 100 percent well with them … I was enrolled in Madison Memorial where I played soccer for the team,” Armando said. “I was well, but I kept wanting more. I felt lonely, I was the only Cuban there.”

It was around this time that Armando said he started getting into trouble. He was hanging out with other Cubans in the area, but he said they weren’t all in school. They committed petty thefts like stealing cars.

“Then, my sponsor dad came to get me one day and all the Cubans were very happy because they knew him. He looked at me and knew right away that my situation was not great. He brought me all my soccer gear. He wanted me to focus on soccer. But he didn’t realize I was already gone to the other side. That hurt me,” he recalled.

Today,Armando is in his 50s. He works in Madison and has a daughter. But even decades later, you can see the regret and sadness in his eyes when he talks about what happened.

“If I could change something about my past, it would be to finish high school in Madison. We weren’t thinking about ‘making it.’ We weren’t talking to each other about this, either. We all forgot about our sponsors, and we also wanted to get away from the situation in Cuba,” he said.

He tried to make it right with his sponsors. Unfortunately, he could only make amends with one of them, Nancy. Dennis died in an accident in 2007. Upon his passing, Armando reached out to Nancy and the two talked for hours, he said, and he asked for her forgiveness.

“We weren’t thinking about ‘making it.’ … We all forgot about our sponsors, and we also wanted to get away from the situation in Cuba.”

Armando Rodriguez said.

Marcos Calderón: ‘We have a group of people… This is what keeps you going’

Marcos Calderón lives in La Crosse. He’s close friends with Ernesto Rodriguez and Rodosvaldo Pozo. They’re all practically brothers, and all came to the U.S. as part of the 1980 Mariel Boatlift and stayed at Fort McCoy.

The three friends enjoy playing music together in Erne and Pozo’s living room. The walls reflect the lives of two men living between two worlds: family photos and Cuban artwork, and a big Miller Lite/Packers flag.

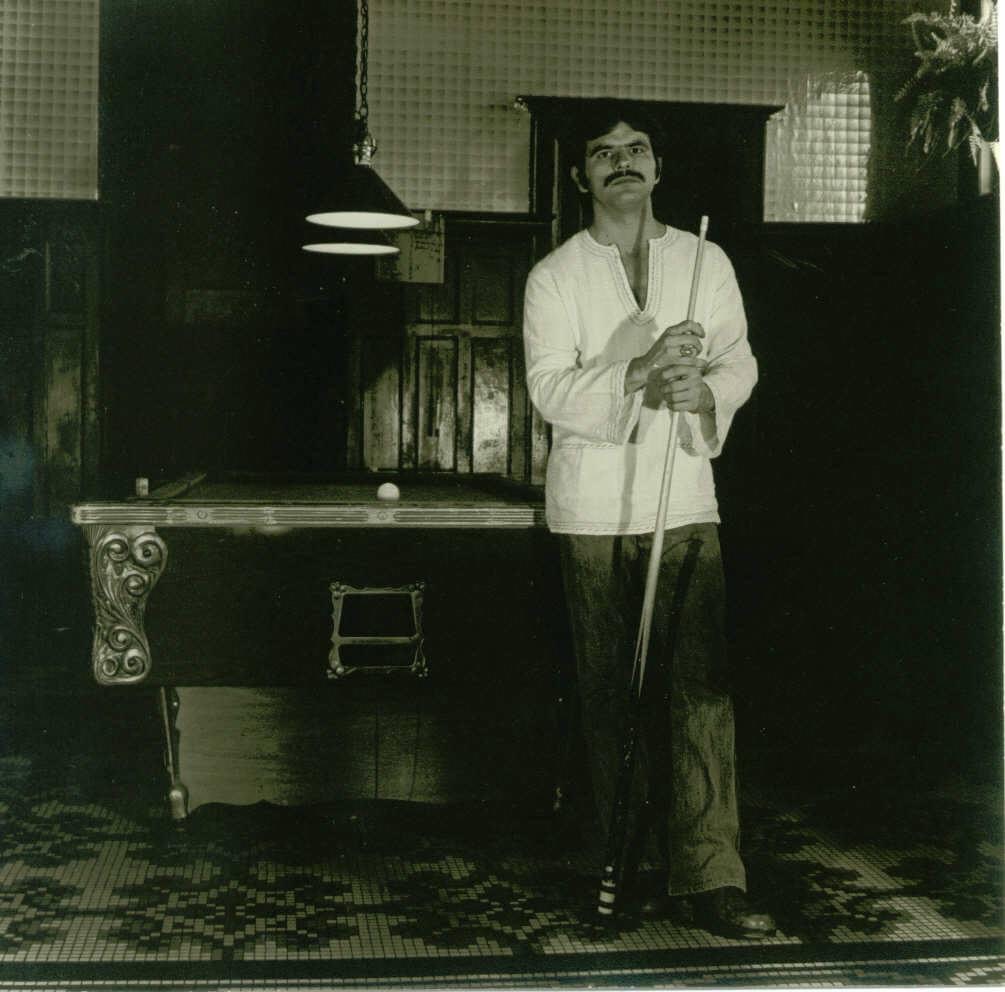

Calderón was born in 1957 and grew up in Havana, Cuba. He’s from a vibrant, touristy neighborhood called Vedado. In the early 1960s, Havana was the epicenter of culture, Granados said. There was music, nightlife and casinos.

“When I was growing up, in my area, (it was) pretty much like being in Vegas. You know, back in the day, you had different languages, people walking around doing their own things out there,” Calderón said.

As a kid, Calderón loved swimming in the ocean and playing marbles with his friends. When he was about 12, he got paid to wash and park cars across from the luxurious Hotel Capri.

Those drives started a lifelong love of cars for Calderón.

He had a much different childhood than Pozo and Erne, who served in the Cuban military and spent time in prison there. Calderón didn’t serve in the military due to a leg injury and he never went to Cuban prison.

But like his friends, he wasn’t a fan of the Cuban government during the country’s revolution. He wanted to drive more cars, travel, see the world. And that wasn’t what the revolution expected of him.

“You cannot leave the country to visit anywhere,” Calderón said. “When Castro, when the communists, took over, Cuba became a prison. That’s what I like to say about that.”

When the Mariel Boatlift got underway in April 1980, Calderón saw his opportunity to get out of Cuba. His mother supported his decision and said he wouldn’t have much of a future staying in Cuba.

But as Calderón boarded the boat bound for the U.S., he was heartbroken.

“All I was thinking (was), ‘When am I going to see my family again? … What is my new life going to be?’ And it was sad. Today, (it) is still sad,” he said with tears in his eyes.

Calderón landed in Key West, Florida, the day he turned 23. When he stood on the shores of Florida, he was crushed that he had to leave his old life.

Shortly after landing in Florida, Calderón was sent to Fort McCoy.

This is something Calderón doesn’t talk about a lot. He doesn’t mention much of what happened at the camp in the 25 days he was there.

He met a family of farmers early on who were working in a Fort McCoy mess hall, and that family ended up sponsoring him.

“They were a beautiful family. We talked, you know, I know a tiny little (bit of) English — not enough to defend myself, at least to understand what they were (saying),” he said.

The family didn’t know Spanish, but the mom bought a dictionary to try to communicate with Calderón and the other refugees they sponsored. They also developed their own sign language and drew things to communicate with one another.

Calderón said he helped 17 refugees find sponsors after he left Fort McCoy.

“All I was thinking (was), ‘When am I going to see my family again? … What is my new life going to be?’ And it was sad. Today, (it) is still sad.”

Marcos Calderón

Eventually, Calderón moved out on his own and needed to find work. Back in Cuba, he studied electrical plant engineering. But he struggled with school in the U.S. since he had a hard time writing in English.

Wisconsin’s technical colleges did offer refugees English classes and classes to help them get jobs, said Granados. But not many refugees stuck with them. Plus, Granados added, taking classes in English doesn’t guarantee a job placement.

For Calderón, struggling with the language and classes meant he didn’t go back to engineering school. Instead, he found other jobs. He worked at a food bank in Minnesota for more than 10 years. And his career has always involved one of his first loves: cars.

“I drive many, many different type(s) of transportation out there. I drive for (the) handicapped, buses, vans, limousines, taxis, city buses … Then I moved to Tomah and I finally got a job as a truck driver, too,” he said.

His favorite job was driving people with disabilities.

“These people, they want to get out of the house. They want to meet with other people. They want to go to work. They didn’t hardly get paid. And this is just like a recreational thing for them to get out and do something different,” Calderón said.

“They didn’t feel sorry for themselves. They say, ‘I am still alive. So I’m going to go ahead and do as much as I can,’” he added. “Sometimes, somewhere, somehow, I was feeling that I was them.”

But Calderón isn’t driving for work anymore. A few years ago, he was diagnosed with bone cancer; his doctors don’t want him working.

“I’m surviving. I pray to God every day. You know, we have a group of people, friends. And this is what keeps you going,” he said.

The Cuban community in La Crosse — Calderón’s friends and chosen family — are supporting him.

And playing music helps immensely. The living room jam sessions mean the world to Calderón, Pozo and Erne.

They’ve been through so much together. Growing up in Cuba during the revolution, surviving a treacherous boat ride across the Florida Straits, waiting at Fort McCoy for sponsors, being Black Cuban men in predominantly white American communities, finding jobs — which was sometimes difficult — and starting families.

Life hasn’t always been easy. Most of their fellow Cubans left the area after leaving Fort McCoy. So, why did they stay?

Some, like Erne, had great sponsors that became family. He fell in love, had kids and found a job.

Calderón found a job and a family in Wisconsin, too. But his reason to stay was part of a bigger plan.

“To be honest, I don’t want to really be in Miami, California, or any of those places where people speak Spanish. I want to go to someplace where I can learn the language along the way,” Calderón said.

Calderón is resilient. He’s constantly growing. He doesn’t want the easy way out; he keeps trying to make it. This is a core instinct of being a migrant, Granados said.

“I did have a dream to come to this country and go pretty much everywhere in the whole world. You know, that dream is still pending,” Calderón said.

And sometimes, wanting a dream so desperately led some refugees to make decisions that have haunted them later in life.

On the next episode of “Uprooted”: drugs, jail time and the attempted murder of a notorious serial killer from Wisconsin.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.