Mariel refugees have built lives in Wisconsin for 42 years, but still long for Cuba

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 8: traducción al español próximamente

It’s a Sunday night in downtown La Crosse. People are beginning to trickle into the Popcorn Tavern, a longtime live music bar. Tonight, it’s Cuban music night.

To the right of the stage is a huge spread of food: slow-cooked pork, plantains, rice and beans. There’s a blessing before people fill their plates. After dinner, the musicians take to the stage and the crowd hits the dance floor.

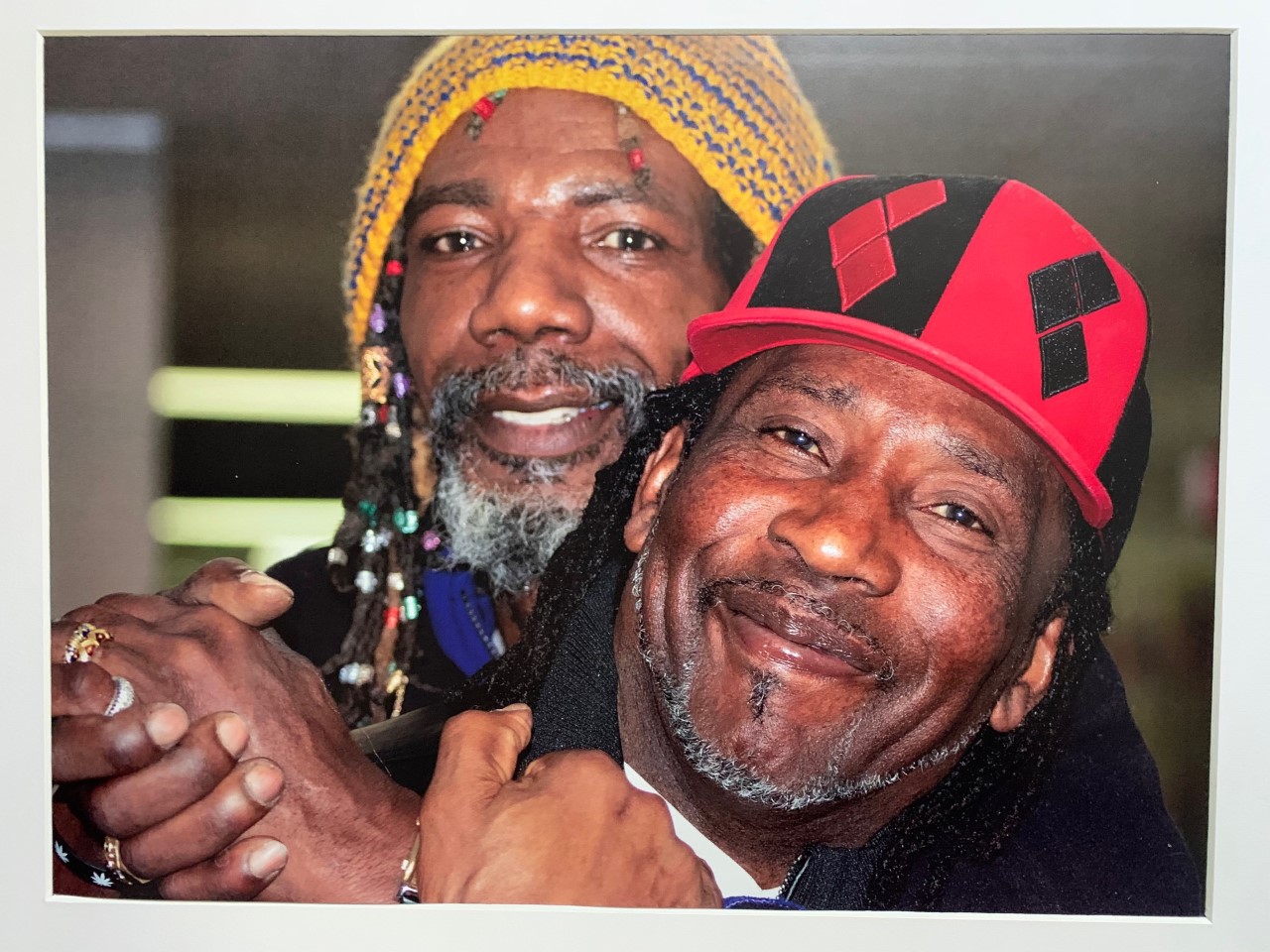

On stage, Rodosvaldo Pozo sits behind a drum set, his dreadlocks swaying with the music. Marcos Calderón is dressed in a flowing black and white polka dot shirt and plays the saxophone, which he just started teaching himself. Ernesto Rodriguez is wearing a Cuban jersey, smiling big while playing his signature bongos.

These Cuban exiles who arrived in Wisconsin in 1980 as part of the Mariel Boatlift have become bandmates, friends and family to one another.

They’re also deeply connected to their Midwestern hometowns. When they play live in downtown La Crosse, they bring together Cubans and welcome non-Cubans into their world, sharing music and stories.They are Wisconsinites.

Now that these men are in their 60s, they’ve spent most of their lives in the United States. But their hearts remain in Cuba, and they still want to visit their homeland one more time.

If they can find a way.

Longing for home

Osvaldo Durruthy, of Madison, has a Cuban flag above his dining room table. The country where he was born is always on his mind — even if he hasn’t seen Cuba in more than 40 years.

“My No. 1 vision is to be able to one day visit my country, embrace my family and bring clothes and whatever they need,” Durruthy said. “I got my family waiting for me, you know. My sister says, ‘My brother, before I die, all I want (is) to see you.’”

“The first thing I want to do, I want to embrace her, raise her up and … give her the hug that nobody ever … she never get that hug before,” Durruthy said, smiling. “She said she’s going to cook for me.”

“My No. 1 vision is to be able to one day visit my country … I got my family waiting for me.”

Osvaldo Durruthy

Pozo, who lives in La Crosse, also wants to visit Cuba. More than anything, he wants to see his mother. She’s in her 90s.

“I want to go see my mama before she dies. God willing. And my family,” Pozo said. “My mama love me with all her heart to this day.”

And then there’s Pozo’s friend, Calderón, also of La Crosse.

“If I have the chance to go back home, the first thing will be going to the cemetery where my mother’s buried,” he said.

Calderón’s eyes filled with tears as he thought about returning to Cuba and visiting his mother’s grave. In the more than 40 years Calderón has lived in the U.S., many of his family members in Cuba have died, including his father and one brother.

“I (want to) give him my respect. Thank (him) for the way they educate me,” he said. “(It was) a lot of hard work to make a place for food on the table so we all can eat, you know?”

For Calderón, the dream of returning home is becoming more urgent than for the others. He has bone cancer. It’s his dying wish to go back to Cuba — to visit his home one more time.

“I’m going to die. But this is when you realize I’m dying no matter what … cancer or no cancer. I’m going to die, simply. So (I) use that to help others and that’s my intention. I’m trying to be happy,” he said.

Paths to residency and citizenship in the U.S.

Many Cuban exiles are able to visit loved ones in Cuba once they become residents or citizens of the U.S.

In comparison to other immigrant groups in the U.S., Cubans have a much clearer path to permanent residency and citizenship due to the Cuban Adjustment Act.

This was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966. It provides Cubans with a streamlined, unique way to obtain a green card and eventually become naturalized citizens.

Under this law, Cubans can become U.S. residents after physically being in the country for one year. They also have to prove they’re Cuban through documentation and prove that they were admitted into the country by an immigration officer — someone who officially checked them in.

The Refugee Act of 1980 was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter. It offered a pathway for all refugees, not just Cubans, to become permanent residents within one year.

It raised the limit on how many refugees the U.S. would accept annually to 50,000. It provided refugees with settlement and financial assistance, as well as job training and English language lessons. It also clarified that a refugee was a person with a “well-founded fear of persecution.”

Just one month after the Refugee Act became law, the Mariel Boatlift was underway in April 1980. Many of the Cubans arriving in Florida feared persecution from the Cuban government because of their political leanings, sexuality or religion.

Carter initially said the U.S would admit up to 3,500 Cuban refugees who stormed the Peruvian embassy under the Refugee Act of 1980.

However, the Mariel Boatlift brought so many Cubans to the U.S. in such a short time that the U.S. would have hit its annual refugee admission limit in a matter of weeks.

According to Carl Bon Tempo’s book “Americans At The Gate,” the huge number of Cuban exiles arriving led the U.S. to change course when it came to the Refugee Act of 1980.

Plus at the time, Cubans weren’t the only people from the Caribbean coming in large numbers to the U.S. in 1980 because of political repression — thousands of Haitians were also arriving at the shores of Florida and had been since the early 1970s.

In June 1980, the U.S. government responded with the Cuban-Haitian Entrant Program. The official designation for Cubans and Haitians was now “Entrant w/ Status Pending.” They were not being granted asylum immediately, and legally, they were not refugees.

From the very beginning, the Mariel refugees have been racialized as part of this larger group of immigrants, said Omar Granados, associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.” They were being treated much differently than Cubans who had come in earlier waves of migration in the 1960s and 1970s.

This designation was intended to be temporary — but it ended up having huge consequences. According Bon Tempo, this status change created an unclear immigration status for the Mariel exiles. Also, they didn’t receive as much aid as other refugees — like Cubans who had come in the 1960s.

According to Bon Tempo, “The ‘entrant’ status expired after six months, and Carter left the decision of whether to extend that status in Congress’s hands. Congress responded by repeatedly extending the ‘entrant’ status and, in October 1980, providing the Marielitos with full access to government resettlement funds. In 1984, Congress finally ‘normalized’ the Marielitos’ immigration status by amending the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act, placing them on the path to permanent residence or citizenship.”

Fabiola Santiago, a Miami Herald staff columnist who covered the Mariel Boatlift and its impact in Florida for many years, said this left the refugees in limbo until 1984 since they could not adjust under the Cuban Adjustment Act.

“So for five years, they were completely status-less. They couldn’t buy a house. They couldn’t travel. They really were like undocumented, except that they were not subject to deportation,” Santiago said. “Cuba just wouldn’t take them. So nobody tried to deport anybody because Cuba wasn’t going to take them back.”

Santiago said there were community efforts to help the Mariel Cubans in Florida, but federal lawmakers didn’t want to take up their cause due to the criminal stereotype attached to the Mariel refugees.

She said once stories about the Cubans stuck in limbo became more widespread, it put pressure on local officials to do something about the issue.

“I did a piece that featured a pianist who could not go give a concert in Bogota and an artist who could not exhibit in Mexico City. These stories started to come out and pressure was put on Miami’s growing political structure,” Santiago said. “Eventually, then (the Mariel refugees) were allowed to begin the process of getting residency, which then led to citizenship.”

That process of becoming lawful permanent residents, or green card holders, started around 1984. It meant the Mariel refugees could live in the U.S. indefinitely. They could own property, get financial aid for higher education and join the U.S. military. But they couldn’t vote or get a U.S. passport.

“Cuba just wouldn’t take them. So nobody tried to deport anybody because Cuba wasn’t going to take them back.”

Fabiola Santiago

No easy path to citizenship

But applying to become a permanent resident had its challenges, especially in Wisconsin. Just because the Mariel refugees’ parole status ended didn’t mean they automatically got a green card.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the Mariel folks did not do that in a timely fashion,” said Steve Laxton, an immigration attorney with Matousek, Laxton & Davis law firm in Sparta.

Laxton actually became an immigration attorney because of the Mariel Boatlift. He worked in a kitchen at Fort McCoy in 1980 while Cuban refugees were living at the base. It’s there he developed an interest in the Spanish language and Latin American affairs.

Laxton said in many cases, Mariel refugees in Wisconsin who could have gotten their immigration status changed just didn’t fill out the paperwork.

“I think a lot of people thought, ‘Well, they let me in, end of story,’” he said

Laxton added that many Cubans in Wisconsin didn’t have guidance on how the laws worked or a long-term support system from their sponsors, unlike in places such as Florida, where the large Cuban American community often helped Mariel refugees navigate the system.

Besides confusion surrounding the immigration process, there was another issue holding some Cubans back from becoming U.S. residents or citizens: their drug convictions.

“A lot of the cases we see now are people that come to me — they have that problem. They didn’t obtain the residence when they could have and then they ran into criminal law problems,” Laxton said.

If you commit a felony in the U.S., it can stay with you for a long time, even if you’re a citizen. In some states, you lose the right to vote. In some, you can’t carry a firearm. In others, you can’t get a visa to travel to certain countries.

It’s something that impacted many Cuban exiles like Calderón, Pozo and Durruthy. Since they were convicted of felonies for selling drugs, particularly cocaine, they’re not eligible for citizenship.

“Drugs are really tough because the only exception under the immigration law is for the use of 30 grams or less of marijuana for individual purposes,” Laxton said. “Any other type of drug offense is just lethal under the immigration law. There’s no waiver available.”

Since some Cuban Wisconsinites have been convicted of selling drugs, the only way they can become citizens is if their cases are overturned, the charges are amended or they receive a pardon.

People like Calderón, Pozo and Durruthy were convicted of drug crimes 30 to 40 years ago, at the height of the War on Drugs and when opinions on drugs were more conservative.

“You’ve certainly seen a liberalization of that at the state law level in recent years, where a number of states have decriminalized or legalized at least the use of marijuana. And I think there’s been some revisiting the idea of the harshness of drug laws, certainly with citizens of the United States, particularly in African American communities, where you have a high, way-too-high level of incarceration over fairly innocuous drug offenses. I think you see some modification of it, but there’s been nothing that’s happened on immigration law on that side,” Laxton said.

Marijuana is legal in many states now, but not in Wisconsin. But the laws have not changed for other drugs, like cocaine. That impacts the status of Mariel refugees who were caught with the drug decades ago.

Stuck in deportation limbo

On top of barriers to becoming a permanent resident or citizen, the Mariel exiles with drug convictions are also at risk of deportation.

“If you have a drug conviction — particularly a drug trafficking conviction — that’s going to result in you being put into deportation proceedings if you’re not a U.S. citizen. And a lot of guys received deportation orders,” Laxton said.

Enrique Moré and Pozo were held in immigration detention centers in Milwaukee and Chicago for months. The reasons vary and are unclear.

Pozo said he was detained when he went to renew his work permit a few years ago. He said he was in immigration detention in Chicago for about six months.

But Cuba wouldn’t take him back. They don’t allow people with felony convictions back into the country. Even if Pozo wanted to go on his own free will, Cuba would not accept him. Despite being released from the detention center, Pozo could still be detained or deported at any point.

It makes Pozo uneasy. He gets fired up when he talks about it.

“I pay taxes. My family is paying taxes. So why are you going to keep me in limbo? Every time you want, you’re going to put me in jail for no reason. I haven’t committed (any crime. They haven’t given me due process right. This 14th amendment … this is a cruel, unusual punishment, an amendment violation,” Pozo said.

And there isn’t much clarity from the government on what’s going on.

Wisconsin Public Radio reached out to various federal agencies like the U.S. State Department, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, but the agency’s representatives did not provide answers to these questions.

There is a 2001 U.S. Supreme Court case that ruled people cannot be held indefinitely even if they’re being deported. They have to be released after 90 days. So how is the U.S. able to detain people, like Pozo, for months on end?

Laxton said there’s an exception to the ruling.

“Unless there was a significant likelihood that the deportation could be executed, then the person had to essentially be released and they set up a process where there’d be a review at six-month intervals. If you’ve gone through that review process and you’ve been released, then they give you work authorization, sort of a suspension of deportation status. You’re still legally deported. They can’t effectuate the deportation. So you’re kind of in a limbo,” Laxton said.

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court also ruled that Mariel refugees could not be held indefinitely, a fate that had been placed on about 750 Cubans who arrived in 1980.

The Mariel refugees under deportation orders can continue to live in the U.S. They can get a work permit and driver’s license, but they could still be deported at any time — especially if the U.S. and Cuba improve their diplomatic relationship, said Granados.

In spring of 2022, the two governments met to talk about whether Cuba would start accepting more deportees, but not much has changed.

Regrets and dreams

Calderón, Pozo and Durruthy say they regret past decisions that have left them unable to get citizenship. They said they’ve paid for their past crimes, but the charges stick with them.

“We’ve been here. We pay taxes. We work, but we have no rights at all,” said Calderón, who was convicted of a drug charge in 1988 in Minnesota. “We pretty much just started here without having the opportunity to become an American citizen or resident.”

“It’s very sad because sometimes we live in a state of nervousness, you know, because you don’t know (if) something’s going to happen and will immigration come in, like, ‘Go to Cuba under deportation.’ And you just never know for no reason,” Calderón continued. “In 1991, I got out and since then all I have done is work, work, work, work, work and no more crime. Nothing. And no second chance.”

Calderón wants a second chance, so he can visit Cuba one more time. But without a U.S. passport — which you can only get if you’re a citizen — he can’t leave the country.

For Cubans with a green card and a Cuban passport, traveling to other countries is possible, Granados said.

But Calderón, Pozo, Durruthy and many other Cuban exiles don’t have any of those documents.

“Why can’t Cubans get a second chance, so they can go see their mama?” asked Pozo who was caught with cocaine in the early 1990s. “Because we have been abiding citizens since we committed the crime.”

Pozo said he wants federal officials to give their cases a second look in hopes it will get them out of limbo.

Durruthy was sent to prison after selling cocaine to an undercover police officer in the early 1990s.

“I remember the past. We’d been committing a lot of crime, doing a lot of the wrong thing. But, you know, everybody has done wrong in life, man. Even though it’s been 40 years, you know … We’re not perfect. We just want to be part of the American dream, you know?” he said.

They’ve been chasing their vision of the American dream since they left Cuba in 1980, Granados said.

Lillian Guerra, author and professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida, said access to the American dream has a lot to do with race.

“These cases of people who were desperate to return (to Cuba) speak to how traumatic their lives have been here and how inconsistent their knowledge of the United States is,” Guerra said. “Many people think that they believe the American dream exists and they don’t understand that the American dream only existed for those who were white.”

And while some groups, like Italian Americans and Irish Americans became part of that dream through the rise of unions in the 1950s, Guerra said other groups like African Americans and Puerto Ricans weren’t included.

“Latinos in general were not unless they managed to come with a certain degree of accumulated historical advantages,” Guerra said. “You could have been penniless, but if you had a medical degree, you knew how a system worked and how to get ahead in a new one.”

“We’re not perfect. We just want to be part of the American dream.”

Osvaldo Durruthy

A step closer to Cuba

As he sits around a table in La Crosse, Ernesto Rodriguez’s phone rings. He’s getting a video call on WhatsApp from his older sister in Cuba.

He introduces his sister to everyone around the table, including Pozo and Calderón.

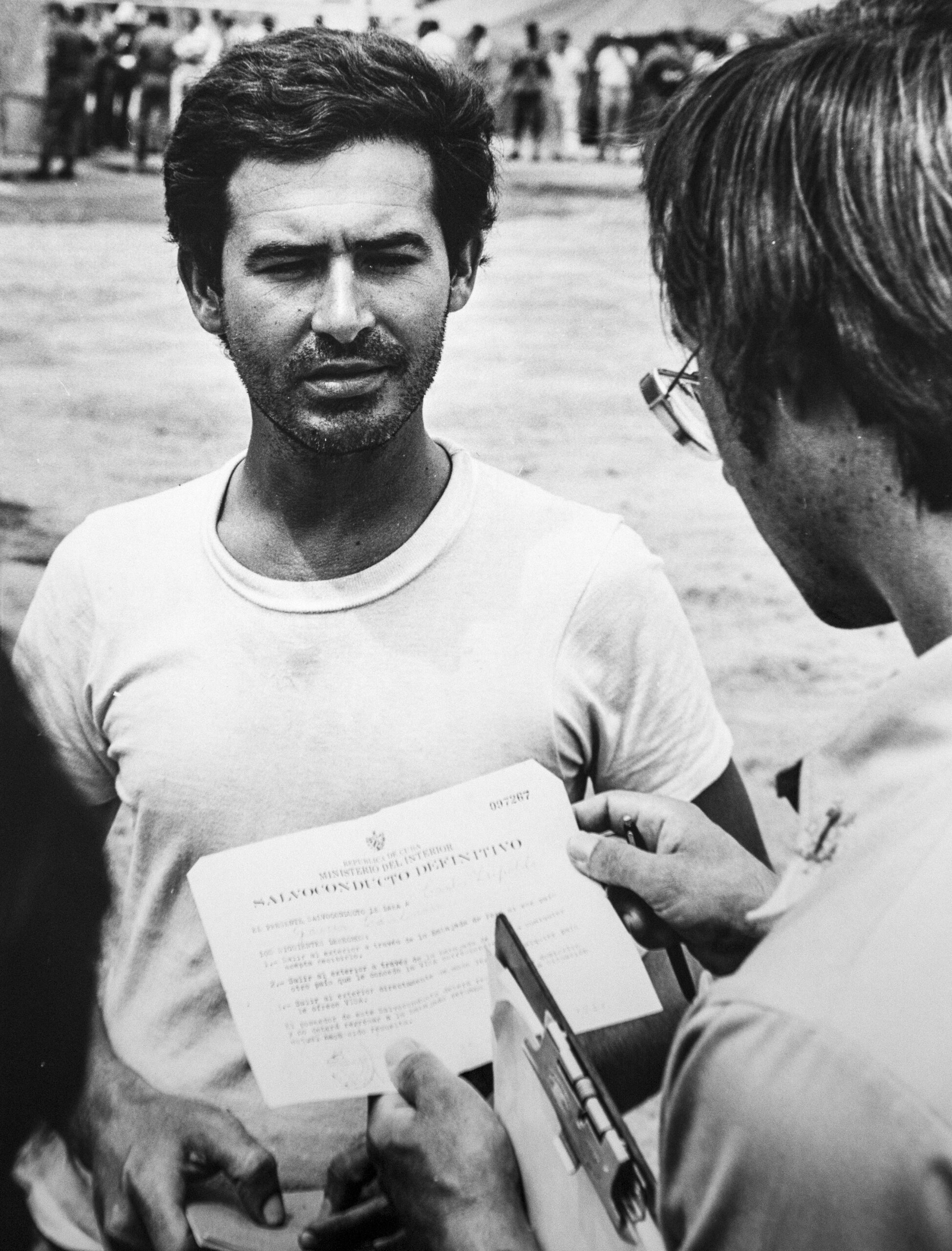

The siblings haven’t seen each other in person in nearly 50 years, since he was in a Cuban prison before hopping a boat to come to the U.S. during the Mariel Boatlift.

These calls are one of the only ways Ernesto can stay connected to home, a place he hasn’t stepped been in more than 40 years.

“Of course I want to go and visit,” Ernesto said after hanging up the phone. “I have a lot of family I never met before, like nieces and nephews, great nieces, great nephews. Anytime I talk to them it’s, ‘When (will) you come?”

But unlike his friends Pozo, Calderón and Durruthy, Ernesto can return to Cuba. He’s a permanent resident of the U.S. He got his green card in 1981. Plus, his “papers are clean,” meaning he was never convicted of a felony. All of these factors open the doors to traveling back to Cuba.

And when he does return, the first thing Ernesto wants to do is visit his hometown, Camagüey. He wants to check out a massive sugar mill he used to work at and see if it’s still up and running.

He also wants to visit his grandmother’s grave and walk around his old neighborhood.

“See if I recognize where I used to live. See if the house is still there. And then, I’ll go to Florida and spend time with my family,” said Ernesto, smiling. “Maybe I (will) take three weeks in Havana — party in Havana.”

Plus, eat roast pig and congri.

But Ernesto can’t go just yet.

That’s because there’s a problem with his paperwork. Ernesto’s name on his birth certificate doesn’t match his Cuban I.D. The name he’s used his whole life is Ernesto Rodriguez Ruiz. But his dad signed a different name on his birth certificate: Nestor Rodriguez Cruz. It’s unclear why this happened.

Even with a green card, Ernesto needs a Cuban passport to visit his homeland. But because his Cuban names don’t match, he doesn’t have all the documents he needs to travel.

He’s submitted paperwork to straighten out his situation with the Cuban embassy in Washington, D.C. and that decision is still pending.

There is one way Ernesto could get to Cuba sooner. If he legally changed his name in the U.S. to what’s on his Cuban birth certificate — Nestor Rodriguez Cruz — then he could get his Cuban passport and go back, Granados said.

But Ernesto doesn’t want to change his name. Sparta attorney Steve Laxton has been working with him and has told Ernesto to change his name — but hewon’t do it, according to Granados.

“It’s his identity. As much as he wants to go to Cuba, he doesn’t want to become someone else in the United States,” Granados said.

This is a source of contention among Ernesto’s Cuban friends who can’t return. They don’t understand why he won’t just change his name. They say they would change their names in an instant if it meant they could go back to Cuba.

Advocating for themselves

Despite the systems working against them, Rodriguez and the other Cuban Wisconsinites remain optimistic about the prospect of returning to Cuba.

“Over the last few years, they’ve come to better understand the racism and discrimination they’ve faced. They’ve started advocating for themselves,” said Granados. “They’ve agreed to be interviewed for this podcast. They participate in panel discussions.”

Calderón agrees.

“I’m 65 years old. Wow. Things go fast … I haven’t given up. I have faith (I can) go back to Cuba,” he said.

Calderón plans to meet with Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers’ staff to share his story. He’s talked about organizing rallies to bring attention to the Mariel refugees’ situation and get lawmakers to pay attention. He’s explored the possibility of asking for a pardon in Minnesota, where he committed his crime in 1988.

Pozo talks about doing the same in Wisconsin.As of August 2022, Evers has issued 603 pardons, more than any other Wisconsin governor.

More than anything, Calderón wants to become a U.S. citizen. It’s not just to go back to visit Cuba. He wants to vote. He wants to travel the world.

“Enough is enough for people that pretty much have been in this country more than they have been in their own country,” Calderón said. “I want the law to change. I want people to hear our voices. I want people to know we are legal in the United States of America. We were welcome into this country.”

Calderón acknowledged that he and some of his friends committed crimes when they were young.

“They didn’t exactly know what they were doing the majority of the time. They were trying to survive because they were making the money,” Calderón said.

And then there’s Durruthy. Thirty years ago, he thought the only way he could go back to Cuba was by killing Jeffrey Dahmer and getting deported.

His mindset has changed a lot since then.

“Me and my Cuban guys, if we don’t come together and try to ask for forgiveness, we (are) never gonna be heard,” Durruthy said.”We want our voices to be heard. We want our voices to do something for us … to be able to conquer what we (have) been seeking for years and years and years. This is the land of opportunities.”

Durruthy is asking for another chance after being released from prison in 2016.

“We pay for our mistakes. Twenty … 30 years, most of us did (it) in (the) penitentiary,” Durruthy said. “We are in our 60s … we are not a threat to society anymore.”

“Whoever listens to us, we (are) … asking for forgiveness. Asking for consideration. Asking for (an) opportunity to grow as a man, as a father, as a husband,” he continued.

The Cuban Wisconsinites were closely watching when the Biden administration granted clemency to some drug offenders in spring of 2022. And like many people, they’re waiting to see if the Biden administration will normalize relations with Cuba.

They’re also keeping tabs on Cuban news, as well as what’s going on with immigration from other Latin American countries. But so far, there haven’t been many signs that lawmakers or government agencies are looking to change policies that would impact this group of Cuban Mariel refugees.

Several government agencies were contacted while working on this podcast, but none agreed to comment.

As much as these men want to go back to Cuba, they really want to stay in Wisconsin. They’ve lived most of their lives here. As hard as things have been, most of them love the state — they have kids, friends, girlfriends and a band. They don’t want to be deported.

What’s next?

No one has gone back to Cuba. They’re all still waiting.

In the meantime, Granados continues to work with the Cuban refugee community in La Crosse — to help tell their stories through the “Uprooted” traveling exhibit and very soon, a virtual exhibit.

If there are any big updates in the lives of the Cuban Wisconsinites — like if someone makes it back to Cuba — we’ll bring you their stories here on “Uprooted.”

As for the people you’ve met on this podcast:

Ernesto Rodriguez’s papers to return home are still not in order. In La Crosse, he’s gotten involved in a latin dance group.

Rodosvaldo Pozo continues to play percussion with La Crosse musicians and loves watching Cuban boxing online.

Marcos Calderón is still teaching himself the saxophone, and he’s eager to change things for Cuban refugees politically. He’s also been talking more publicly about his cancer diagnosis, hoping to inspire people to push through their own treatments.

Armando Rodriguez is living in Madison and works driving a forklift. He often drives to La Crosse to see his friends, like Pozo, Calderón and Ernesto.

Enrique Moré, who “likes to play music too much,” just wrapped up another recording session with his band, Mr. Blink.

And Osvaldo Durruthy hopes he opens his mailbox one day and finds a letter from immigration, saying he’s a lawful permanent resident of the U.S. Then he could go home to Cuba one more time — a dream that hasn’t always felt within reach.

- Durruthy became his neighborhood’s Laundry Man as a young child.

- He turned to pickpocketing to feed his family.

- He was sent to Cuban prison during the Castro regime.

- Then he was shipped off to the U.S. as part of the Mariel Boatlift.

- After arriving in Florida from Cuba, he was sent to Fort McCoy.

- He didn’t find a sponsor while at Fort McCoy, so he was sent to Fort Chaffee in Arkansas.

- From there, Durruthy was sponsored by a millionaire in Nashville.

- He survived multiple gunshot wounds from fights as he adjusted to life in the Midwest.

- Durruthy was arrested and sent to prison in Wisconsin.

- He was released in 2016 and has been starting his life over.

Durruthy isn’t a person who would just give up on his dream of returning home to Cuba.

“I hope (it) happens,” he said. “It’s all we’re looking for, you know? Hopefully one day, you guys remember us and give us the opportunity to do that. Thank you very much. Thank you. God bless America.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.