Sharks, apples and capitalism: Cubans take refuge in US after Mariel Boatlift journey

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 4: traducción al español

Editor’s note: This article contains brief mentions of violence and language that may be inappropriate for some audiences.

It’s late spring 1980 in Cuba.

Osvaldo Durruthy, at age 22, sits on a bus, making his way across the country from a prison cell in Santiago de Cuba to the Port of Mariel. He’s getting his first taste of freedom in years, but this bus ride is anything but relaxing.

Durruthy lives in Madison today. But on this day back in 1980, as he’s sitting on this bus in Cuba, he doesn’t know what his future holds.

He’s focused on the present — worried that the bottles protesters are throwing at his bus could bust through his window.

“There were people in the street throwing bottles of beer and sodas,” Durruthy recalled. “(They were shouting) ‘Get out of here! Get out! ¡Que se vaya! ¡No lo queremos!’”

These protesters considered Durruthy a traitor because he was one of the nearly 125,000 Cubans who were leaving their homes, hospital rooms or prison cells and fleeing to the United States as part of the Mariel Boatlift, which lasted from April to October 1980.

The bus eventually made it through the protesters, but there was one more stop before the Port of Mariel: El Mosquito. Durruthy and others who were sent there described El Mosquito as chaotic and scary.

“(It) was like another city full of people, you know, full of Cubans. It was surrounded by fence,” Durruthy remembered. “They had oatmeal, they give us a meal. There were women, niños, all kinds of people at the Mosquito, waiting for the next day to go to Mariel. At the Mosquito, there were a lot of fights, all the crazy stuff.”

After a couple of days at El Mosquito, Durruthy was finally on his way to the Port of Mariel where thousands of people were waiting to get on boats. He remembers some people without clothes or wearing clothing from prison.

Durruthy watched these boats for an entire day, wondering which one would take him to his new home. Although the scene was chaotic and unlike anything he’d experienced, Durruthy was excited. Looking back, he says he never could have expected what his life would become after leaving Cuba’s shores.

The Laundry Man

When he was 7 years old, Durruthy started his first business. He was a budding entrepreneur in his hometown of Santiago de Cuba, armed with a skill his mother taught him: laundry.

“I became so good (at) washing and ironing that the whole neighborhood had to deal with me. They say, ‘You too good! We’re going to pay you … to wash our clothes and to hang our clothes,” Durruthy said.

Durruthy became known as “The Laundry Man.” This job was significant — not only because he still loves ironing his clothes — but because it laid the groundwork for thinking ahead when it came to survival.

Even at 7, Durruthy had to make money for his family. His father died when he was young, leaving his mother, Norka, to raise two kids on her own.

“I’m proud of her because … she was (a) good mother. We never go to sleep hungry, ever. She teach me how to iron clothes, how to wash her clothes. We had to do laundry every day, and we do it by hand,” Durruthy said.

But he said sometimes things took a turn with his mother.

“Norka, she was the mother any child wished to have. Except … don’t make her angry,” Durruthy said. “I grew up with my mom beating me up, you know, a lot. That is something that I carry with me.”

As Durruthy grew up, the neighborhood’s Laundry Man needed a job that paid better. He turned to pickpocketing, and he said he was good at it.

Because of that, he saw pickpocketing as a trade amid a culture of limited options, said Omar Granados, an associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.” One reason people turned to petty crimes was because food rations were not enough to feed their families.

But pickpocketing eventually landed Durruthy in prison. As he sat in prison at age 22, he heard about the situation at the Peruvian embassy, which led to the Mariel Boatlift.

“Jimmy Carter was the president at the moment,” Durruthy said. “But behind his back, (Castro) also (cleaned) all the penitentiaries, saying he’s sending all the killers and rapers and murderers and he open(ed) all the mental hospital facilities. So that was how we ended up here.”

News about the Mariel Boatlift traveled fast. People made their way to the Port of Mariel in western Cuba from provinces across the island, including Durruthy. He left his prison cell in Santiago de Cuba in the southeastern part of the country, hopped on a bus bound for Havana and joined the mass exodus.

The exiles

On May 1, 1980, Fidel Castro gave a speech at a May Day rally where he criticized the Cubans who wanted to leave.

“(Castro) would say that there was a genetic defect that made them non-revolutionary. They’re genetically deficient, so they need to get out,” said Lillian Guerra, author and professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida.

“He who has no revolutionary genes, he who has no revolutionary blood, he who does not have a mind that adapt to the idea of a revolution, he who does not have a heart that can adapt to the effort of heroism required by a revolution: We do not want them; we do not need them.”

Fidel Castro, May 1, 1980

Guerra said about 40 percent of the people who left through the Mariel Boatlift were picked up by relatives. She said the rest self-registered, meaning they filled out paperwork at a police station and declared their desire to leave. People had to prove they were not revolutionary through self-confession as they were leaving Cuba.

The Cuban government was oppressive toward its country’s LGBTQ+ community at the time.

“You could say, ‘I’m a lesbian, my daughter is a wh—, my husband’s gay and all of us want to leave,’” Guerra said. “You got a certificate, which is your pass from the police station that identified you as an antisocial.”

No one in Cuba was fact-checking whether people were actually lesbians or running a bordello out their home. Castro wanted people to self-demonize because he didn’t want to admit that his societal promises weren’t working for everyone, Granados said.

There was no path out of Cuba, unless peopled marked themselves as criminals.

“Many people were stunned because the folks who went out and said they were human trash…were highly respected members of their society,” Guerra said.

“I have documented presidents of Committees of the Defense of the Revolution who presented themselves with their entire family to get out of the country. You could imagine that they were subject to a three-week period of intense mob violence on their home, because they were the ones who were the greatest traitors. They were the ones who admitted that they had just been faking it. They had just finally been able to get out, and they wanted to give their kids a different life than the one that had been chosen for them,” she continued.

A treacherous journey across the Florida Straits

Some of these soon-to-be exiles were told to just hop aboard a boat for a free ride at the Port of Mariel to get to the U.S. Some passengers were specifically trying to get to their family there, and some of those living in the U.S. were paying captains thousands of dollars to pick up their Cuban relatives.

As weeks went by, people were packed onto boatsto get more people out of the country quickly. According to U.S. Coast Guard documents, at least one captain said the Cuban government forced him to more than triple his capacity, to overload his boat, otherwise they would seize it.

Two of the people who boarded separate boats at the Port of Mariel are now Wisconsinites and live together in La Crosse: Ernesto Rodriguez and Rodosvaldo Pozo.

Rodriguez was placed on a boat after being released from prison — a fishing boat with about 80 people on board. Pozo also came to the port after being released from prison and was directed to a different fishing boat.

The trip across the Florida Straits would be traumatic for Rodriguez and Pozo.

“It was scary in the middle of the sea. Oh, my God. We got a lot of people there, and (a) baby crying,” Pozo said. “And I see a boat behind me … a wave came, and they didn’t come out. I was so scared.”

Rodriguez had spent a lot of time on the water since he was a child, but this journey was unlike anything he’d ever experienced.

“The ocean in the beginning was calm. But when we was in the middle of the ocean, that’s when it (started) to whoosh. And that’s when a lot of boats sink. People drown,” Rodriguez added. “People get sick. I’m used to the ocean. But a lot of people are not used to the ocean … the puke and the smell of the sea.”

Durruthy — the Laundry Man — also survived a devastating boat ride. During his journey from Cuba to the U.S., he sat at the front of a huge shrimping boat.

The waters became violent. The boat was rocking. Durruthy could see sharks swimming in the water, surrounding their boat. He witnessed people fall out of the boat — and get attacked by sharks.

“I had a friend of mine who lost his leg,” Durruthy said.

Durruthy said a helicopter pulled his friend out of the water. This was most likely the U.S. Coast Guard, whose forces were patrolling the waters to rescue people who fell over or were packed on overcrowded boats.

“It was late night. And they were looking for salvation. I see a friend … I only saw one leg. Blood all over. In the ocean, (it) was all gray; too many sharks eating, feeding,” Durruthy remembered. “So you know, there were those who made it, there were those who (did) not. Guess what? I made it! I made it. Thank God, thank God, I made it.”

News reports say 27 people died while crossing the Florida Straits during the Mariel Boatlift — from April to October 1980 — but some believe many more drowned. That information is not officially reported.

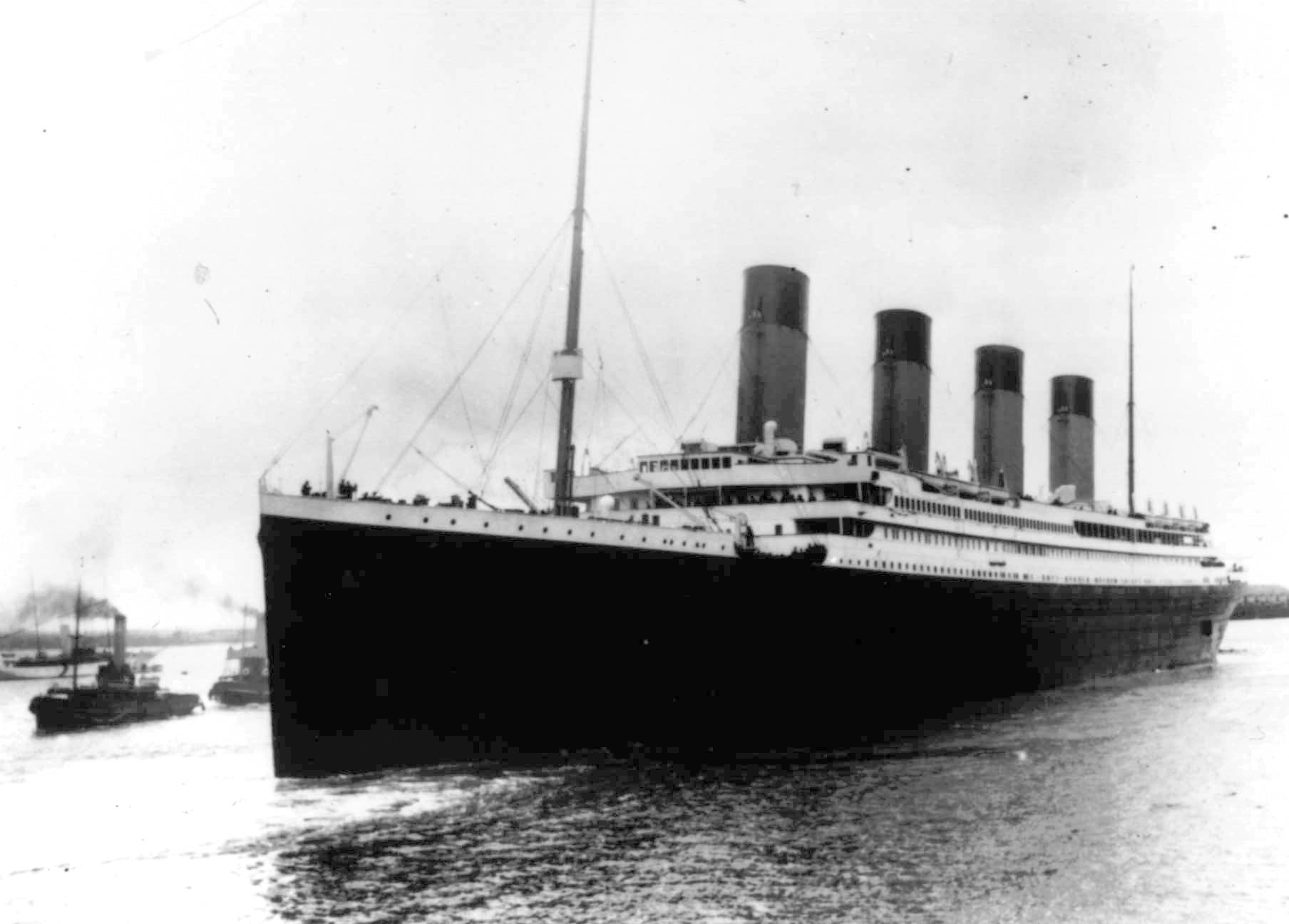

About 1,700 boats journeyed between Cuba and the U.S. during that time, according to Florida archives.

“In fact, there’s a lot of information we don’t know about because we don’t have access to the official Cuban documentation or an archive on what happened at the Port of Mariel,” Granados said. “All we know about what happened on the Cuban side of the Mariel Boatlift is through stories and memories.”

“And I see a boat behind me … a wave came, and they didn’t come out. I was so scared.”

Ernesto Rodriguez

Key West: ‘It all comes at a cost’

After a long, grueling boat ride, the Cubans eventually landed in Key West, Florida.

“I was so glad to be part of America. That was my dream,” Durruthy said. “We made it, too, from the Mosquito to Mariel, from Mariel to United States … from the boat to Key West.”

Rodriguez was also ecstatic to get off the fishing boat.

“When I got to Key West, I get up, I get off the boat and I kissed the ground,” Rodriguez said.

Volunteers and government officials waited for the refugees at a processing center in Key West. They handed out goods like clothing, blankets and food— most notably, apples.

“That was the first time (I) saw an apple in my life,” Durruthy said, smiling. “Some people want to save it. I wanted to eat it. … I love it for the first time!”

Rodriguez got two apples — something he hadn’t eaten since 1964. To drink, he had something he’d only tried once in his life.

“I went with a Coca-Cola,” Rodriguez said, laughing. “I ask, ‘Can I have one more?’ They say, ‘Yeah,’ and then (I guzzled it fast.) The guy said, ‘You’re gonna choke!’ And then I said, ‘No comprendo.’”

After Rodriguez finished chugging his two Cokes, he recalled being led to a mess hall. It was his first all-you-can-eat buffet experience.

“We never see food like this … everybody was (like), ‘Oh, this America,” Rodriguez said. “(We had) a good meal that day. They gave us chicken and macaroni and cheese and black-eyed peas. We had a blast.”

This was a big deal coming from Cuba where food rations were the norm.

There were many other adjustments these Cuban refugees went through, one being the language barrier. And while many Mariel refugees had heard about the American dream, they’d never experienced living under capitalism, Granados noted. These refugees had to learn about health insurance, leases, bank accounts, credit cards and car payments, as well as adjust to privatization.

“You go from a place where there’s no private property, moving into a world where everything now is private. You’re moving into a world where the state doesn’t provide your food or your rations or your health insurance. More importantly, you go from having no options to suddenly having 100 types of different cereal,” Granados said.

“But it all comes at a cost,” he added. “You have to have money, and you have to have a job to be able to participate in that economy and buy that cereal.”

“You’re moving into a world where the state doesn’t provide your food or your rations or your health insurance.”

Omar Granados

The moment the Cuban refugees stepped off the boats in Florida in 1980, they had people waiting for them, including refugee assistance groups and government agency workers.

But it wasn’t always a warm welcome from the greater community, said Michael Bustamante, an associate professor of history and the Emilio Bacardí Moreau Chair in Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami.

“To put it bluntly and to make a long story short, the Mariel refugees — even in the heart of the Cuban American community — were not received with the kind of open arms that the first cohorts of refugees had received in the early 1960s,” Bustamante said.

He said the early Cuban refugees and the Mariel refugees came from the same country, yet completely different worlds. The early Cuban exiles were mostly professional, had money, were of upper or middle classes and were white.

“It’s one thing to have left the island in 1961, 1962, when you’ve experienced two years of this thing called ‘the revolution’ in power. It’s quite another to have been educated under it or to have lived under it for 20 years, right?” Bustamante said. “The kinds of memories and experiences that people have under their belt, I think, are just different. The points of reference that they have, the ways that they have learned to get by, the codes of everyday behavior and expectations are just different.”

Refugees in the media

As for the rest of the U.S., the way many people got acquainted with Mariel refugees came from Hollywood. If you don’t live in Miami or near one of the refugee resettlement camps — like Fort McCoy, where some Mariel refugees ended up — everything you know about Mariel refugees you may have learned from “Scarface.”

The movie focuses on fictional Mariel refugee Tony Montana, and his rags-to-riches story of becoming a major kingpin in the Miami drug trade.

The movie came out three years after the refugees arrived in the U.S. Al Pacino, who’s Italian American, was cast in the main role of Tony Montana, who is Cuban.

“Scarface” is significant because it introduces the American public and a global audience to the image of a Mariel refugee, Granados said. Tony Montana is a ruthless, violent gangster, someone who doesn’t seem to value familial relationships.

Granados compares the lack of interpersonal connection in “Scarface” to the familial focus of the gangsters portrayed in “The Godfather.”

“This is a new stereotype (in ‘Scarface’) that we’re starting to see in Hollywood, (he) doesn’t really value his relationships with his family. He’s got difficulty relating to his sister and his mother. We don’t see scenes like we see in ‘The Godfather’ where the family gets together on Sunday for dinner,” Granados said. “This is a major change in the way in which we’re talking about criminals in Hollywood. So for all of its box office success, this film also created a harmful stereotype, an immediate backlash from the Cuban American community in south Florida.”

The way the movie “Scarface” portrays Tony Montana isn’t too different from the way the news media portrayed many Mariel refugees.

Jillian Marie Jacklin is a lecturer in democracy and justice studies, history and women, gender and sexuality studies at UW-Green Bay. When she was getting her doctorate in history at UW-Madison, she published a paper that examines the media coverage of Mariel refugees.

She said the U.S. media portrayed the situation like Castro was getting rid of scum — or escoria — and releasing Cuban criminals to the U.S.

“But then again, embedded within that message was that it was the responsibility of the U.S. government and U.S. citizens to at least detain these people to show that the U.S. is a democratic nation that would accept anybody, especially people wanting to flee communism,” Jacklin said.

“If this person named Fidel Castro is this awful dictator who does sort of everything wrong and in the opposite way that the U.S. government would do it,” Jacklin added, “Then, why would … the U.S. national media then take everything that he’s saying at face value?”

The media’s messaging was a victory for Castro since the U.S. press ate up everything he was saying about his own citizens, Granados said. While some people came from troubled pasts, there was no way to verify who was a criminal since records were not shared.

Granados said the media was trying tochase sensational stories and failed to dismantle the narrative that Castro created.

Of the 124,779 Mariel refugees who arrived in the U.S, 1,761 of the refugees — or 1.4 percent — were hard criminals, felons who were convicted of murder, rape or burglary. Then, 23,927 Cuban exiles — or 19.1 percent of the refugees — were considered “non-felonious criminals and political prisoners.” This is according to Immigration and Naturalization Service numbers cited in “Castro’s Ploy – America’s Dilemma: The 1980 Cuban Boatlift” by Alex Larzelere.

Some dangerous people came to the U.S. via Mariel. But most of the people sent to the U.S. from Cuban prisons were guilty of things like petty theft, using marijuana, being gay and criticizing the communist government.

But the narrative that the Mariel refugees could be dangerous was the one that took hold.

‘Era of growing fatigue’

While U.S. immigration history is not exactly full of warm welcomes, the late 1970s were a time when the U.S. had already accepted several waves of Cubans, plus plenty of people from Southeast Asia who were fleeing various conflicts.

In March 1980, Carter signed the Refugee Act of 1980 into law. It essentially opened U.S. doors to more refugees and also clarified some immigration policies. But a month later, the law was put to the test just as the Mariel Boatlift got underway. In mid-April, Carter agreed to take in 3,500 Cuban refugees who stormed the Peruvian embassy as part of the Refugee Act.

But by mid-May 1980, Carter put a halt on private boats leaving Florida and returning with refugees. Carter proposed a more coordinated effort in bringing Cubans to the U.S. through government-backed flights and boat rides, plus refugee screenings in Cuba. But none of it was put into effect.

At this point, about 1,000 Cuban exiles were arriving daily. Not to mention, the U.S. was experiencing a wave of Haitian refugees, who were also being detained. So many people were arriving at Florida’s shores, it put a strain on communities, resources and government agencies.

Bustamante said the U.S. was in an “era of growing fatigue” with immigration policy during this time.

“This is the beginning of, sort of, the rise of the modern day anti-immigrant movement,” he said.

Race also played a role in how welcoming some people were to this new group of immigrants.

Young, single and Black

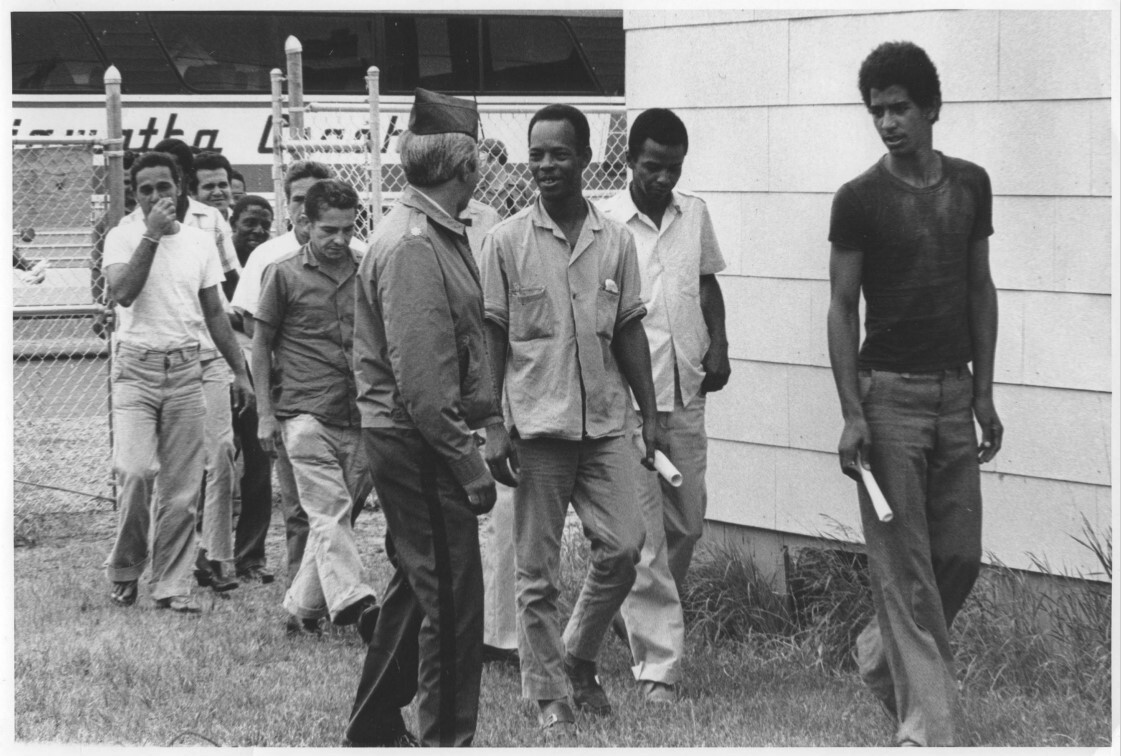

While most of the nearly 125,000 Cubans who left during the Mariel Boatlift were white, about 40 percent were Black or mixed race. Many were also young, single men who were part of the working class.

As the boatlift entered late May and early June 1980, people who were in prison or psychiatric hospitals began arriving in the U.S. In this group of Mariel refugees, there were more Black Cubans, Granados said. Many of these people didn’t have family, friends or networks in the U.S.

“I’ve never seen evidence that there was a purposeful expulsion of Black Cubans, per se,” Bustamante said.

He added that to an extent, the Cuban government took advantage of the moment by sending people from prisons and hospitals to the Port of Mariel. Even though the revolution was attempting to rid Cuban society of racism, structural racism still persisted, Bustamante said.

“The Cuban state would argue that they had made that choice and therefore, they were not needed. (The prisoners) were not good citizens of revolution in Cuba. That they were ungrateful, in fact, of all that the revolution offered them as a path to education and upward mobility,” Bustamante explained.

The exiles already knew how difficult it was to be Black in Cuba. Then they had to learn how hard it was to be Black in the U.S., Granados said. Ernesto Rodriguez said he knew early on that being Black in the U.S. would be a challenge.

“I don’t want to come here,” he said. “The only thing you can see in Cuba is how bad is America. The Ku Klux Klan … and I was so scared because I see all this stuff in Cuba and I don’t want to go (to the U.S.).”

He said he was thankful he made it to the U.S. But he was wary of coming.

Key West to Fort McCoy

When the Cubans landed on U.S. soil, they had to find family or sponsors — a U.S. citizen or an organization who is supposed to vouch for the refugee and help them get started in their new country.

For example, Rodriguez didn’t have much of a say where he ended up because he didn’t have family or a sponsor right away when he landed in Florida in June of 1980.

This was the case for many Black Cubans who arrived as part of the Mariel Boatlift.

“You have Mariel refugees who arrive in Key West and who relatively quickly are sponsored by family members who are waiting for them, are allowed to integrate into the community and therefore have an incredible leg up,” Bustamante said, adding that those without relatives had a harder time settling in. This included a more racially diverse group who needed to find sponsors.

“And so it stands to reason that in the United States of 1980, the Cubans who are Cubans of color are going to (have a) more difficult time finding sponsors, particularly when they are kind of sent away from South Florida,” he continued.

People like Rodriguez, Durruthy and Pozo were all alone on the shores of Florida.

“I was not with family. I was alone,” Durruthy said. “But the people that I know, we all came from penitentiary. We all were single and we (said), ‘Well, whatever happens, happens.’”

Meanwhile, officials were running out of space and homes for refugees in south Florida. The government had to come up with a new plan and find a place for people to temporarily live.

While these refugees waited to find sponsors, the U.S. government started sending them to remote military bases for processing: Fort Chaffee in Arkansas; Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania; Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida Panhandle; and Fort McCoy in Sparta, Wisconsin.

Fort McCoy was the last resettlement camp to open, with the first group of refugees arriving May 29, 1980. Of the almost 15,000 people living at Fort McCoy, many were Black, single males between the ages of 25 and 30, Granados said.

And it’s Fort McCoy where the U.S. government sent people like Durruthy, Pozo and Rodriguez after they landed in South Florida in 1980.

In the next episode of “Uprooted,” the Cuban refugees begin their lives as Wisconsinites after arriving at Fort McCoy. And as they wait for their release, they find jobs on the base, play cards — and they also need to watch their backs.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.