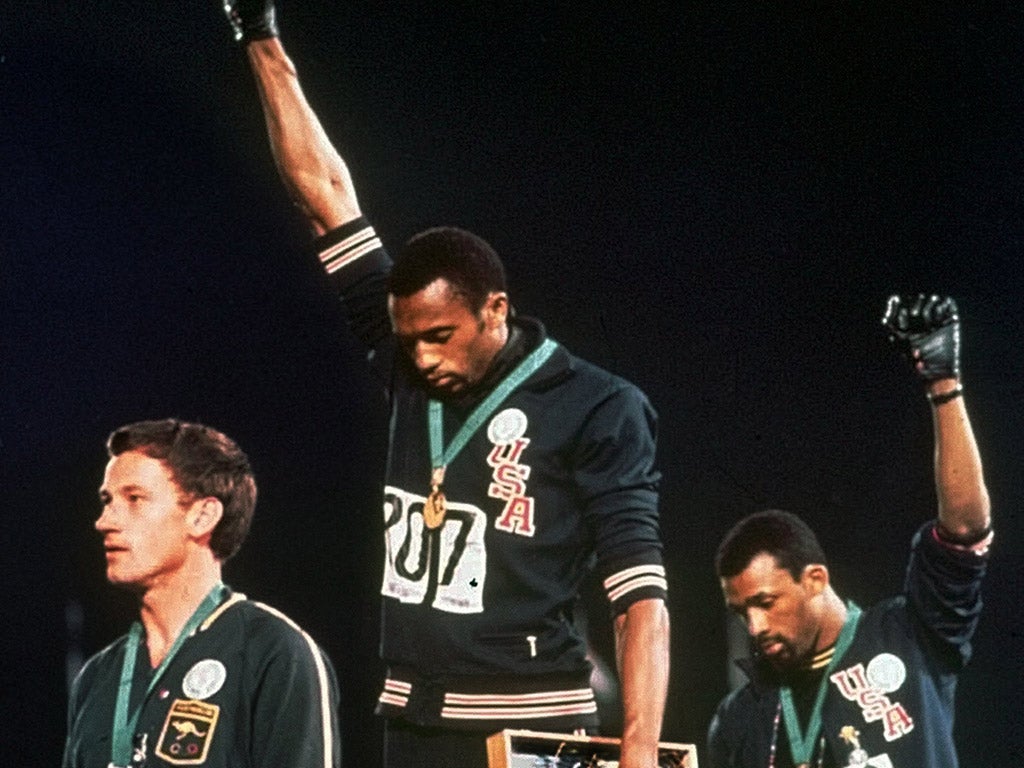

On Oct. 16, 1968, as the national anthem began to play inside Mexico City’s Olympic stadium, John Carlos raised his left hand in a fist. Having moments ago taken the bronze in the men’s 200 meters, Carlos and his teammate, first-place finisher Tommie Smith, took the podium with black socks on their feet and stood with their fists in the air to protest racial injustice across the world.

Their demonstration was met with outrage from members of the International Olympic Committee. Carlos and Smith were expelled from the Games, removed from the Olympic Village and charged with making an inappropriately political gesture. Today, that gesture still marks an iconic moment in the history of the Olympics and the Civil Rights Movement.

But before the Games began, Carlos was still unsure of how best to express his message. Sociologist Harry Edwards and others working with the Olympic Project for Human Rights, including Martin Luther King Jr., had pushed for an absolute boycott of the Games. But after King was killed in April of that year, many black athletes expressed hesitation over dropping out, leaving the group’s plans uncertain.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Included below are excerpts from an interview with John Carlos about a meeting he had with King that inspired him to bring politics to the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

On Meeting King

He noticed right away that I was a little nervous about being in the room. And what I noticed about him was that he was very perceptive, and at the same time, very comedic. He was a jokester to the point where he’d crack so many jokes to relax you. He relaxed me and others in there, I’m sure.

Certain things that he said stuck out in my mind. For instance, he made a statement that they sent a letter to him that he had a bullet with his name on it and he wouldn’t have to wait long for it. The second thing is, he was going to come out in support of the Olympic boycott.

I had two questions. The first question would be, ‘Dr. King, why would you go back to Memphis if they’re threatening your life?’

He said, ‘I have to go back and stand for those who can’t stand for themselves, and, John, I have to go back and stand for those who won’t stand for themselves.’

The second question I had for Dr. King: ‘Did you ever play any sports? Did you play basketball, did you box, did you do anything?’ He said he couldn’t shoot pool. My question was, ‘Why would you get involved in the Olympic boycott?’

He said, ‘John, that’s a better question. Just imagine you’re out in the middle of a lake, and the lake is still and serene. You pull out a rock and you drop it in the lake. What happens? The waves go out to the far ends of that lake. The Olympic boycott is that rock.’ He said it would make a statement that would ripple throughout the world. ‘What would make these individuals step back and give up something they trained for all their lives? Something must be wrong. Let’s have some sort of dialogue and try to have an understanding.’

On deciding to run in Mexico City

Many individuals felt that they worked so hard to win a gold medal at the Olympic games. So it was very difficult for many of them to say, ‘I’m willing to sacrifice my 15 minutes in the sun.’ And we felt that we didn’t have the right to tell them, ‘You must not go to the Olympic games,’ but we did feel we had the right to sit them down and let them know both sides of the table, in terms of what you’re getting in your 15 minutes in the sun and what you could possibly do for humanity. But those individuals felt compelled to go to the Olympic games.

When they decided to go, the question for me was whether I was going to stay home. I felt that the United States at that time was the greatest country in the world, as far as track and field is concerned. Someone from the United States would go and win a medal in my place and get on the victory stand. I really don’t believe that they would have gotten up there and represented John Carlos the way he felt he needed to be represented at that time. So I was compelled to go to the games.

Reflecting on the backlash

(I have) no regrets whatsoever. And if it was necessary for me to step up tomorrow, I would never hesitate to step up for what I feel is right. People say, ‘You sound like you’re still running. You sound like you still got the fire.’ Well, the fire was in me when I came, it’ll be with me when I’ve left, until justice is brought here for all men, women and children on this planet.

Someone has to step up in order to make it better. What good is my life if I’m in a position where I can bring attention to something to try and make us solve this problem, and I haven’t done anything to try and make a better life for my kids and their kids? That’s what it’s about.

Editor’s Note: This article is based on interviews in the most recent episode of the “To the Best of Our Knowledge” podcast. Listen and subscribe here.