For almost five years, the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa has been engaged in a legal battle with Canadian energy firm Enbridge.

The tribe wants to shut down the company’s oil and gas pipeline on tribal lands. They fear erosion near its Line 5 pipeline could lead to an oil spill in nearby waters and Lake Superior.

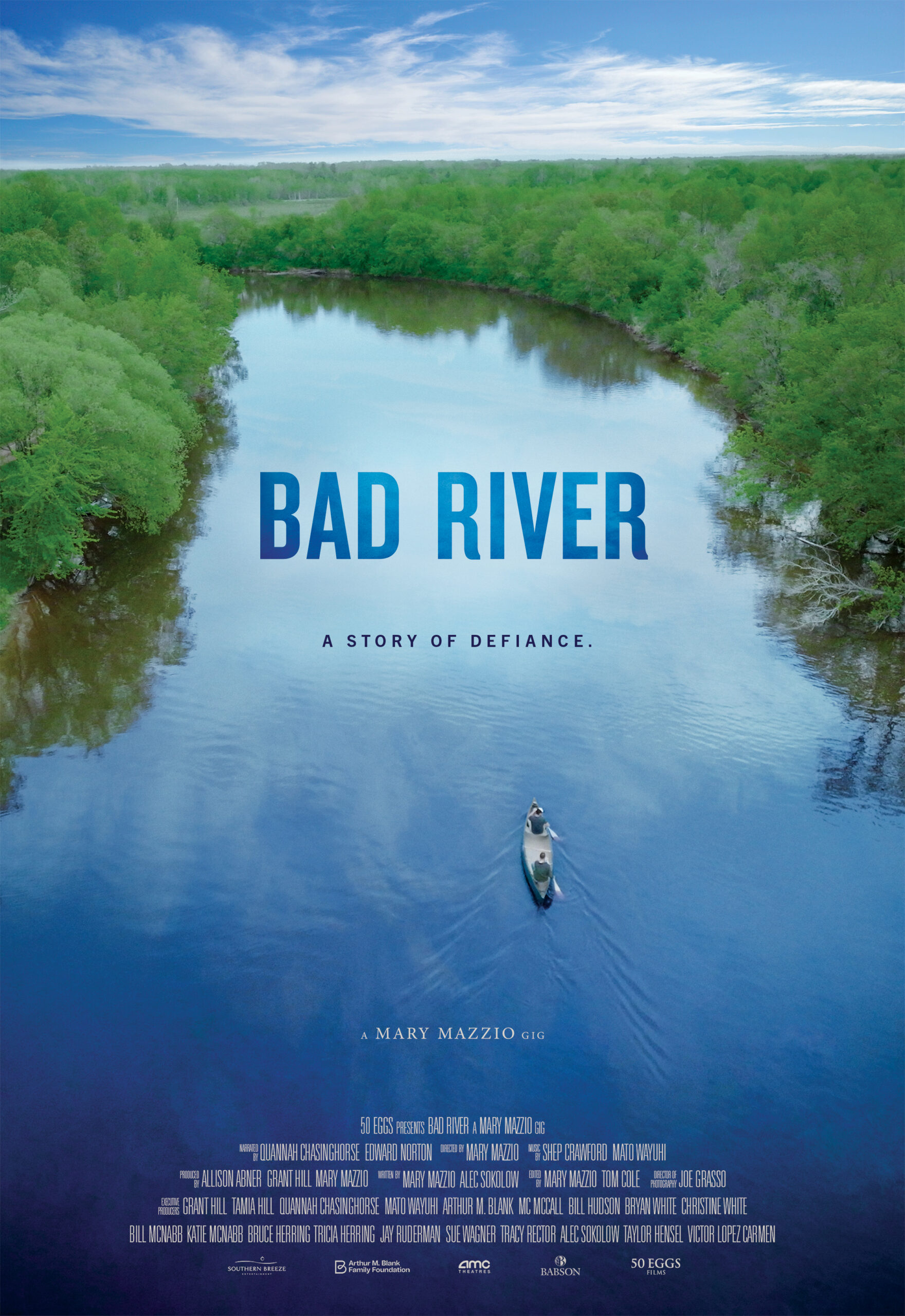

A new documentary called “Bad River” chronicles the tribe’s ongoing fight for sovereignty.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Morning Edition Host Alex Crowe spoke with Mary Mazzio, the film’s director.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Alex Crowe: The film gives a history of the Bad River Band to the present day and their fight to protect their lands and preserve their culture. Can you tell us a bit more about that and why it was important for you to make this film?

Mary Mazzio: So it’s a story about this really small group of people, the Bad River people. And they are, with really monumental effort, trying and fighting to protect a resource, Lake Superior, which is one of the world’s most precious resources in terms of freshwater drinking water. And they’re doing it for all of us, and really at considerable cost to themselves.

And so it’s really an extraordinary story of resilience, of resistance. And as one band member said to me, “Win, lose or draw, we’re gonna stand up for what we believe in, and we’re going to fight the good fight.”

AC: One of the parts of the film that I found interesting was the Walleye Wars that happened in northern Wisconsin during the late ’80s and early ’90s. Can you tell us a little bit about what happened there? Why was it was such a pivotal moment for Ojibwe tribes like the Bad River?

MM: In the course of making this film, what was interesting was we were originally going to focus on the case itself and the challenges with the pipeline operator, but Bad River tribal members wanted to talk about much more than that, including the Walleye Wars. And really, this was a fight over treaty rights.

It was actually a Bad River member who filed a case early on before the Walleye Wars erupted, because he was arrested for fishing on Lake Superior. And he challenged it saying, ‘Look at we have a treaty from 1854 that clearly articulates the right to hunt, fish and gather.’ And so this was pivotal in in many, many ways for the band in terms of not only thinking about their treaty rights, but going on into the future.

AC: And the latest fight in that chapter would be what was focused on in the film. That Line 5 pipeline that the Bad River Band says they want it to be shut down and removed. Can you tell us how that pipeline got built there in the first place, and why this is now an issue?

MM: The pipeline was installed in the ’50s. It was shortly after oil was discovered in Leduc, Canada. The Interprovincial Pipe Line Company , which is the predecessor to Enbridge, needed to figure out a way to bring oil from Western Canada to eastern Canada. The reason the line actually came down into the United States, went under the Great Lakes and then went back to Canada was because it was cheaper, it was easier, you had fewer permitting requirements and the terrain was more forgiving.

Now, fast forward from 1953, when the line was installed across the reservation, to today. The line is now 70 years old. And there’s a juncture in the Bad River where she’s changing her course, and she’s headed straight for the pipeline. The lower court judge in this case found that the risk of rupture was was so great that it could happen with the next flood.

When that line was put in in 1953, it was about 350 feet away from the water’s edge. Today it’s 11. And what hangs in the balance could be catastrophic to Lake Superior.

AC: So the federal judge has ordered that Line Five has to be shut down on the tribe’s lands within the next three years, but that’s being appealed. What are you hearing from tribal members about how they’re feeling now about how things are playing out in court?

MM: It’s really difficult. An open letter to the band was just published, so it’s public knowledge that the band has been offered $80 million to settle the lawsuit. And the current chairman has responded saying our treaty rights are not for sale. Obviously there’s an extraordinary amount of pressure on this small community and the fact that they would turn down $80 million to safeguard this precious resource is jaw dropping in many ways.

You can hear the extended version of this conversation on the Wisconsin Today podcast.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.