For most Wisconsin families and students, shifting back to in-person learning last school year after months of learning from home was a relief.

But there were some students who found they liked the flexibility of virtual learning, or that they thrived in a virtual environment. As the school year wraps up, districts around the state are planning to offer long-term virtual learning to a small but significant number of families who have found that the flexibility, control and distance of learning through a screen might be what’s best for their kids.

At the beginning of the 2021-22 school year, second grader L.B. enrolled in the Racine Unified School District’s virtual school in part because her younger brother is at higher risk of getting severely sick from COVID-19. Now, though, she loves it — she’s excelling in school, enjoying playing with her brother at home, and making friends.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I like it because I get to actually be able to still be with people and have fun with people. For me, I love it, because virtual is like my friend,” said L.B., who goes by her initials at school and whose family asked Wisconsin Public Radio to not use her last name because of privacy concerns.

Her school day is a mix of live meetings or classes and time to work independently. Some days, her class gathers online after school, too.

“We play Among Us and Roblox with my two teachers,” she said. “I get to play the other grades, too.”

Schools began, beefed up virtual programs

Racine had a virtual program before the pandemic, but it had a limited scope.

Full-time enrollees were mostly students with health issues that made it hard for them to be in class, or a sports or dance career that kept them traveling. The district also used its virtual model to offer specialized classes, such as AP math and science courses, that might not have enough interest at a single school to be sustainable, but could attract enough students district-wide.

This year, in the first year of its revamped virtual offerings, Racine has 660 full-time virtual students, up from 180 last year and 100 in the 2019-20 school year.

Other school districts have started new programs in response to demand.

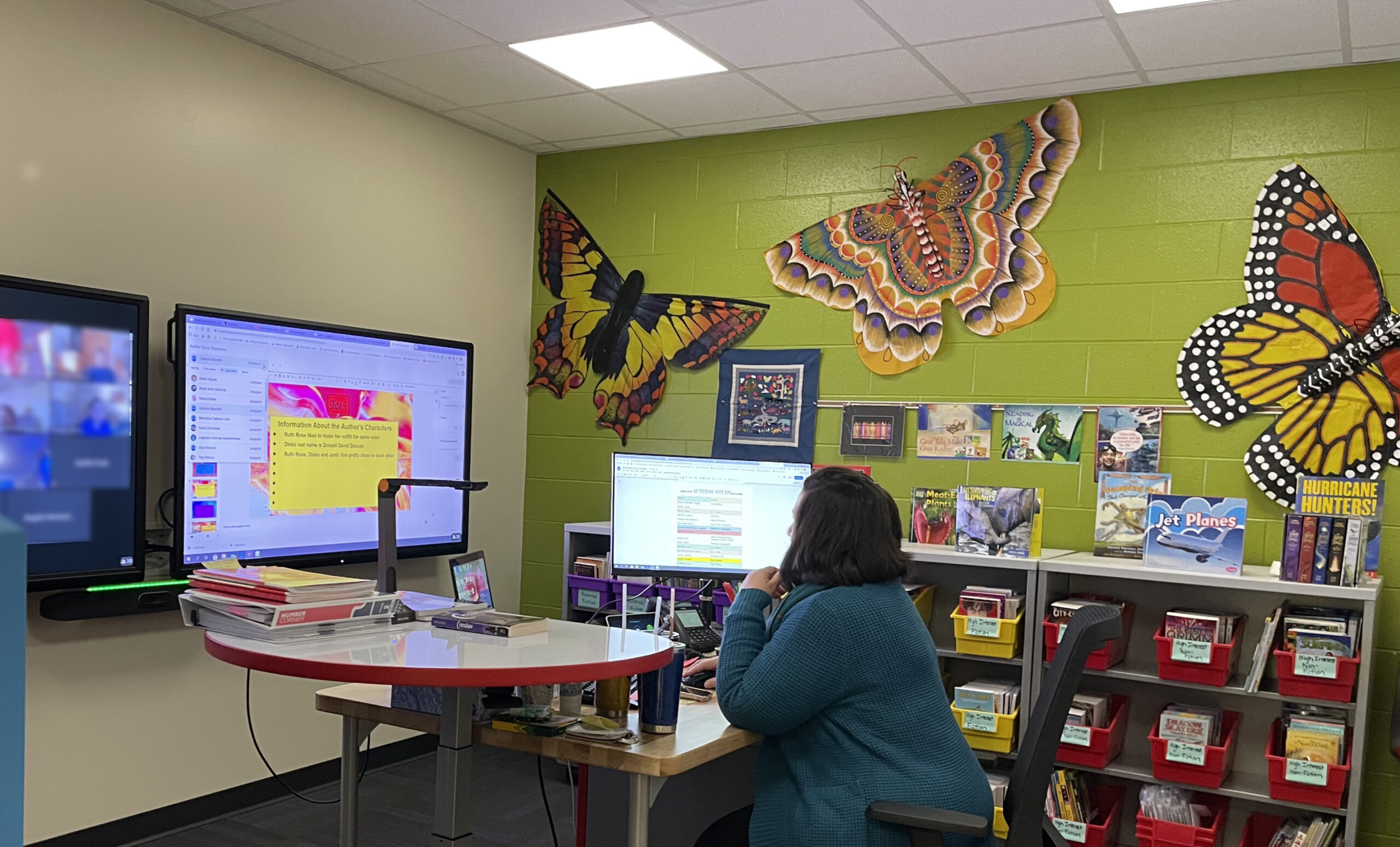

Green Bay built classrooms for virtual teachers that are outfitted with cameras, microphones and other tools to make it easier to teach.

“Last year, everyone was there not by their own choice, but by the choice of the district,” said Tonya Cioni, a third grade teacher in Green Bay’s virtual program. “This year, it’s choices made by the families, and they’re a little more engaged.”

At the Madison Metropolitan School District, Madison Promise has a timeline to add more classrooms for different ages. Virtual charter schools, which handled most of the state’s online learners before the pandemic, have grown — and nine new ones have opened in Wisconsin in the past two years.

In many ways, Cioni said, a virtual school day is like an in-person one — students learn the same subjects, and they’re still occupied from about 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. — they just have more independent learning time and more one-on-one meetings with teachers. Her third graders still earn rewards for doing well, too — the rewards just look different.

“We had a pet parade, where everyone got to bring their pet in front of the camera, show it off, talk about it,” she said. “We’ve done things where it was a karaoke day, and everyone got to sing their own songs in front of each other — it gets creative, but everyone gets to enjoy it.”

Not all this year’s virtual learners will stay

While some districts think virtual learning will be popular enough post-pandemic to make these new or expanded programs sustainable, they say it’s a little too early to tell how many students will stick with it.

All the middle and high school spots in Madison Promise filled up this fall, and interest was so high the district opened up an elementary program as well. But that was when the delta variant of COVID-19 was driving up cases around the state and dramatically increasing cases among children — many students returned to in-person learning before the end of the semester. Next fall, Madison Promise will include grades 4 through 12.

TJ McCray, who directs the Madison program, said Madison Promise has reached a kind of stasis at about 136 students this year, though he suspects some might still be attending because of COVID-19 risk and therefore won’t return next year.

“What we had was a number of students who … at the semester break, they went back to school,” he said. “That could be them making a decision that ‘I’m ready to go back to school,’ or we just had a number of students who did not fully engage, and so they went back to school at the same time.”

Deborah White, a mother of seven children ages 8 to 15 in Racine, said COVID-19 concern was the family’s biggest reason for learning virtually.

“We tend to get sick, not all together but one at a time, so I just felt like it was the most convenient thing for my family, at the time, because we have so many small people in the house,” White said.

One daughter, Ke’Asjia, age 12, is thriving in virtual learning. Another daughter, 14-year-old Keyari, said she really likes it. But the rest of her kids are eager to get back to in-person learning, possibly starting next school year.

Who thrives virtually

For most students, virtual learning isn’t feasible or doesn’t work well.

Virtual learning requires strong internet access, which remains challenging in many parts of Wisconsin. For younger children, it also means an adult or older sibling has to be on hand to keep an eye on them — a challenge in families where all the adults work full-time and the sibling has their own schooling to tackle.

Many students reported feeling isolated during virtual learning, and struggled with their mental health. A lot of students reported trouble focusing or motivating themselves to log in and complete assignments in a virtual environment, so they returned to in-person learning without a grasp on some of their curriculum’s fundamentals.

But for a small group of students, it worked well.

Some, like L.B., found they excel in a virtual environment. Other students found a reprieve from in-school bullying in an online environment. For some students with special needs, the feeling of control offered by learning through a screen, and the distance from classroom distractions that overstimulate them, makes learning much easier.

“I think of one of our families who the son has an (Individualized Education Plan), during the pandemic the student really excelled,” McCray said. “Mom got him on the virtual program, and we’re really seeing some progress with that student.”

The future of virtual learning

Because the pandemic is still ongoing, and children under age 5 can’t yet be vaccinated, virtual programs’ current enrollment might not be a perfect indicator of how many students will learn virtually in future years.

But the programs are planning to scale up. Both Madison Promise and Green Bay, for example, have a timeline for opening up additional grades in their virtual programs, as they’re able to add the teaching staff and gauge families’ interest and needs.

“We were all afraid that we would be recognized as being the COVID school, and that was never the intention — the intention was that people were coming here because it’s what they needed for their lifestyle, or it was a choice that they were making,” Cioni said. “Some got their vaccines and went back to in-person, and some won’t be back with us (virtually) next year, but it seems like a lot will stay, and it was nice to know that we’ve made these relationships online that they can make in the classroom.”

WPR is bringing you stories reflecting on the last two years of the pandemic. They include stories on long haulers, masking, health care workers, education and work. For more stories on COVID-19, visit wpr.org/COVID.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.