I grew up in a small Ohio steel mill town.

My grandmother used to take me to Packard City Music Hall on Saturdays to watch professional wrestling. They sold glazed donuts and beer (grandma used to dip my donut in her beer) and I reveled in the spectacle.

I loved it.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

I booed the villain. I screamed my head off for the hero.

I didn’t know it as a kid, but I needed that catharsis. We needed to feel like there were people like us fighting, fighting against a world that was hitting back with steel mill closures and rising poverty. Also, and at the time I wasn’t sure why, watching violence felt good.

What happened to Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini — a local Ohio boy who made good as a boxing lightweight champion — complicated the idea of idolizing fighters.

[[{“fid”:”1021321″,”view_mode”:”embed_landscape”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duo Koo Kim”,”title”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duo Koo Kim”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_landscape”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EWBA%20Lightweight%20champion%20Ray%20%22Boom%20Boom%22%20Mancini%2C%20right%2C%20watches%20as%20challenger%20Duk%20Koo%20Kim%20of%20Korea%20stands%20on%20the%20scale%20during%20the%20weigh-in%20for%20their%20championship%20fight.%20%3Cem%3EScott%20Henry%2FAP%20Photo%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“alt”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duo Koo Kim”,”title”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duo Koo Kim”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_landscape”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EWBA%20Lightweight%20champion%20Ray%20%22Boom%20Boom%22%20Mancini%2C%20right%2C%20watches%20as%20challenger%20Duk%20Koo%20Kim%20of%20Korea%20stands%20on%20the%20scale%20during%20the%20weigh-in%20for%20their%20championship%20fight.%20%3Cem%3EScott%20Henry%2FAP%20Photo%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”,”title”:”Ray \”Boom Boom\” Mancini and Duk Koo Kim”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]My father would watch the “Fight of the Week” on TV with me and my brother — Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Muhammad Ali. Back then it was 15 rounds of action — that was until November 13, 1982, when Mancini defended his title against South Korean challenger Duk Koo Kim.

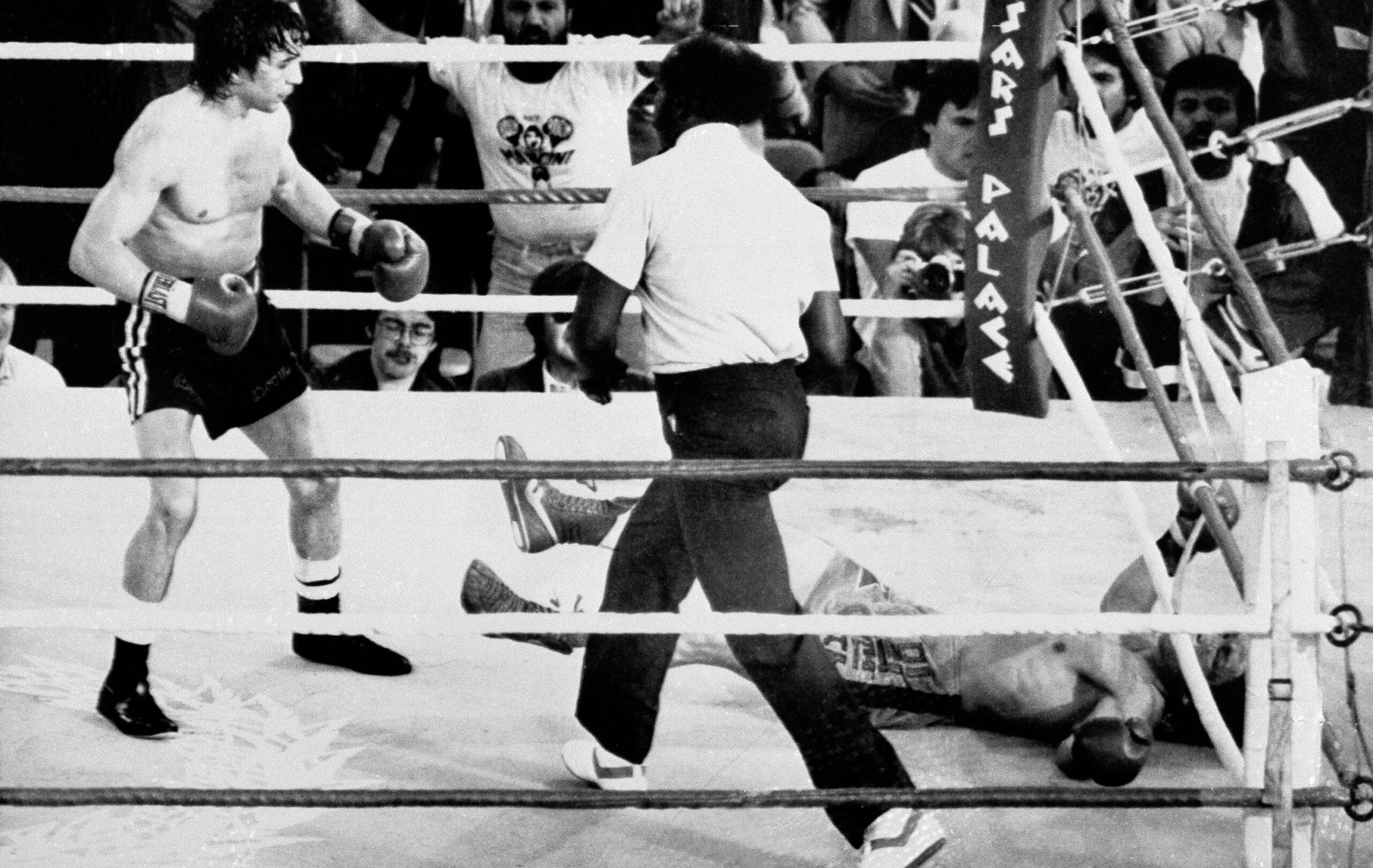

I was in the eighth grade, and like everyone else, I watched him fight live on CBS.

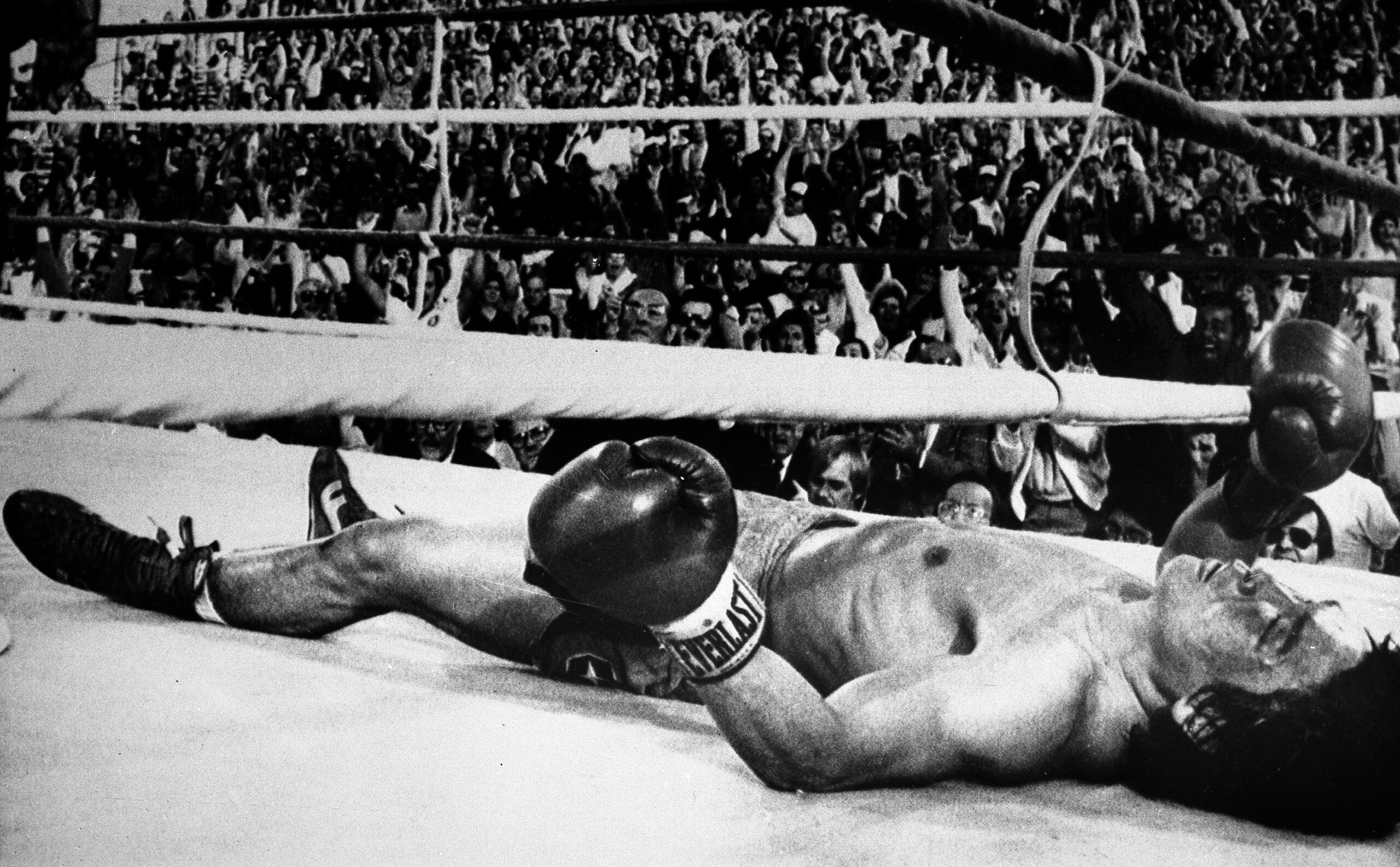

It was an incredible fight, toe-to-toe. Mancini was winning but Kim was tough as hell. Mancini kept hitting him — 45 times in the head in the 13th round alone. And Kim just stood there. He didn’t go down. But as the bell rang for the beginning of the 14th round, Mancini leaped from his stool and — 19 seconds later — knocked Kim out with a vicious right hook.

Kim died of brain injuries suffered in that bout four days later.

I found out on the playground.

In many ways it was my first real loss of innocence. But my loss was small compared to so many others.

Within a few months of her son’s death, Kim’s mother killed herself. So did referee Richard Green. And Mancini never recovered — he became emblematic of everything wrong with boxing. His career and his life fell apart — eventually he left boxing to spend time with Kim’s family in Korea.

Fast-forward to the July 19 boxing match between Junior Lightweights Maxim Dadashev and Subriel Matias that ended in similar tragedy.

Neither had ever lost a professional boxing match when they entered the ring that Friday night. In the 11th round, Dadashev was hit by a series of heavy punches, including dozens to his head. It was brutal.

Dadashev’s trainer, Buddy McGirt, pleaded with Dadashev to end the match at the end of that round. McGirt finally threw in the towel, but it was too late — minutes later, Dadashev started vomiting blood and was rushed to the hospital. He had part of the right side of his skull removed to relieve swelling and was placed in a medically induced coma. A few days later, he died from his brain injuries.

Buddy McGirt, one of the most emotionally intelligent trainers, has always been exceptional with these kind of calls in boxing.

Tragically, even he couldn’t save Maxim Dadashev, no matter how much he begged and pleaded. RIP.pic.twitter.com/2NqFKFZCYp

— Danny Armstrong (@DannyWArmstrong) July 23, 2019

Dadashev was married and had a 2-year-old son. In a press conference before the match, Dadashev was asked why he fights. His answer? To get a green card. Dadashev was a Russian citizen.

A few days after the death of Dadashev, Argentine boxer Hugo Alfredo Santillá also died from brain injuries sustained in the ring. That match, between Santillá and Edwardo Abreu, ended in a draw.

The boxing world is being forced to reckon with not only the violence of the sport but with the brutality of people watching it.

“I don’t know what you learn from a fight like this, other than that it is a violent and dangerous sport,” said ESPN commentator Max Kellerman, speaking on the night Dadashev died. “(It’s) a guilty pleasure for me. You have to ask yourself ethical and moral questions at times like this about supporting the sport. But I consistently come down on the side (that) I love boxing, I’m glad it exists, and this stuff happens sometimes.”

It’s one thing to look at these events strictly as a fan of boxing, but former world title holder Tim Bradley, who was a broadcaster for the Dadashev-Matias fight, spoke with the shared perspective of a fan and a former boxer.

“Dadashev took punishment over the course of 12 rounds (editor’s note — it was actually 11 rounds) and now his life is on the line,” he said, as Dadashev was put into a medically-induced coma. “The only people that (are) there (are) his family. That’s it. Not us the fans, not me the broadcaster, none of that. It’s serious.”

A passionate Tim Bradley talked to media after the Maxim Dadashev bout @Timbradleyjr @trboxing #Boxing #RBRBoxing #LopezNakatani pic.twitter.com/6QwMmVoV33

— Round By Round Boxing (@RBRBoxing) July 20, 2019

The boxing world had to take a look at itself before, back in 1982. The Mancini-Kim fight was dubbed “the fight that changed boxing” — the change being a reduction in rounds from 15 to 12. Dadashev fought until the 11th round; Santillá fought until the 12th.

Perhaps boxing has already seen it’s next fight that will change the sport. The question lingering in the air: can it be changed enough?