At the beginning of this year, Gov. Tony Evers’ proposed spending more than $100 million to address pollution from so-called forever chemicals known as PFAS.

Months later, Republican lawmakers called for even more money, voting to create a $125 million trust fund to address PFAS contamination as part of the current two-year budget, which Evers signed.

The Democratic governor is often at odds with Republicans who run the Legislature, but they seemingly found themselves in the heat of agreement on the PFAS issue — at least in theory.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But nearly six months have passed since Evers signed the budget, and the money has yet to be spent. With time running out on this legislative session, it’s unclear whether it will be.

Here’s a breakdown of where things stand.

What are PFAS?

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals used in cookware, food wrappers and firefighting foam. They don’t break down easily in the environment. High exposure to the chemicals has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, and other serious health problems.

What have the governor and GOP lawmakers proposed to deal with them?

Under Evers’ original budget proposal, the state would have spent $100 million for a municipal grant program. That money would have helped local governments pay for investigating, testing and treating PFAS in water systems. The funds would also have paid for temporary emergency water supplies and 11 more positions at the DNR to address the chemicals.

The trust fund Republicans voted for instead set aside $125 million to address and prevent PFAS contamination, but there are strings attached. Under the GOP plan, spending the money either requires lawmakers to pass a separate bill, or it requires the Department of Natural Resources to get approval from the Legislature’s budget committee.

Why hasn’t the money been spent?

So far, lawmakers have yet to greenlight the $125 million.

In recent days, Evers has accused Republicans of blocking efforts to help people facing PFAS contamination.

“While I was proud of the bipartisan work accomplished in the budget to secure the first real, meaningful investment by legislative Republicans to address PFAS contamination statewide, I am disheartened at the lack of urgency that has followed since,” Evers said in a statement. “Republicans’ continued obstruction of basic government functions is playing politics with our water and peoples’ lives and their livelihoods.”

Republicans have disputed Evers’ claims of obstruction, describing the PFAS debate as a work in progress.

GOP lawmakers did introduce a bill that would spend the money by providing grants to communities and landowners to address PFAS. The same bill would have required the DNR to conduct PFAS research and pilot projects and help labs reduce testing costs and get test results out faster.

That bill passed the Senate last month on a party line vote but has yet to receive a vote in the Wisconsin Assembly.

What’s the sticking point?

Since then, Green Bay Republican Sens. Eric Wimberger and Rob Cowles, the bill’s authors, have been working with Evers, the DNR and other groups to hash out differences.

Wimberger told WPR the sticking point revolves around the agency’s authority to force landowners to clean up the chemicals.

“You have to come up with a way to stop the pollution, to make sure that the right people are called polluters, and the wrong people aren’t,” Wimberger said. “And make sure that the money is available to get clean drinking water and then not financially destroy people going forward in the process.”

The GOP answer to that issue — at least so far — has been to limit the authority of the DNR to test for and clean up PFAS. That has the agency worried.

Wimberger says protections for innocent landowners are a must, since they could otherwise face financial ruin by being forced to pay for cleaning up pollution that wasn’t their fault.

Where does the DNR stand on the GOP bill?

But the DNR has expressed concerns about maintaining its authority under the state’s spills law. That law requires anyone who causes, possesses or controls a hazardous substance that’s been released into the environment to clean it up.

In fact, the bill would prevent the DNR from taking enforcement action against people deemed “innocent landowners” as long as they let the agency clean up the chemicals at the state’s expense.

It would also limit the agency’s ability to require property owners to test for PFAS unless it had probable cause to believe PFAS levels would exceed state or federal standards, a restriction the DNR has said would hurt the agency’s authority to protect public health and the environment.

Where do Democrats stand?

In a legislative session that has seen its share of bipartisan agreement on big issues, Democratic lawmakers have made it clear they don’t support Republicans’ latest PFAS bill.

When the measure came up for a vote in the Senate, Democrats tried to eliminate limits on the DNR’s authority, but GOP lawmakers rejected the proposed changes.

Sen. LaTonya Johnson, D-Milwaukee, who sits on the Legislature’s finance committee, said companies who are causing pollution to drinking water wells aren’t facing consequences.

“And that’s a serious issue because this continues to be put on the backs of taxpayers to provide the money to remedy these issues,” Johnson said.

A recent report from Wisconsin’s Green Fire estimated the cost to install treatment of public water systems or securing alternative water supplies is roughly $208 million. The conservation group says that will likely grow as testing reveals PFAS in more systems and inflation drives costs higher.

While Republicans can pass legislation without help from Democratic lawmakers, they need Evers’ support if it’s going to become law, and Evers has been sharply critical of the plan.

Could a compromise still come together?

Wimberger, the Senate GOP author of the PFAS plan, said he’s “all ears” if Evers has changes to better describe innocent landowners under the legislation.

Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Saukville, who also sits on the budget committee, said in a written statement that the governor’s latest remarks appear to indicate he’s unwilling to compromise.

“It’s a shame that Democrats seem to care more about empowering a handful of DNR bureaucrats than they care about providing clean, safe drinking water for thousands of Wisconsinites,” Stroebel said.

Stroebel said he hopes Evers will “do the right thing” and sign the bill.

Democratic Senate Minority Leader Dianne Hesselbein, a Democrat from Middleton, said she’s still hopeful lawmakers can reach a compromise.

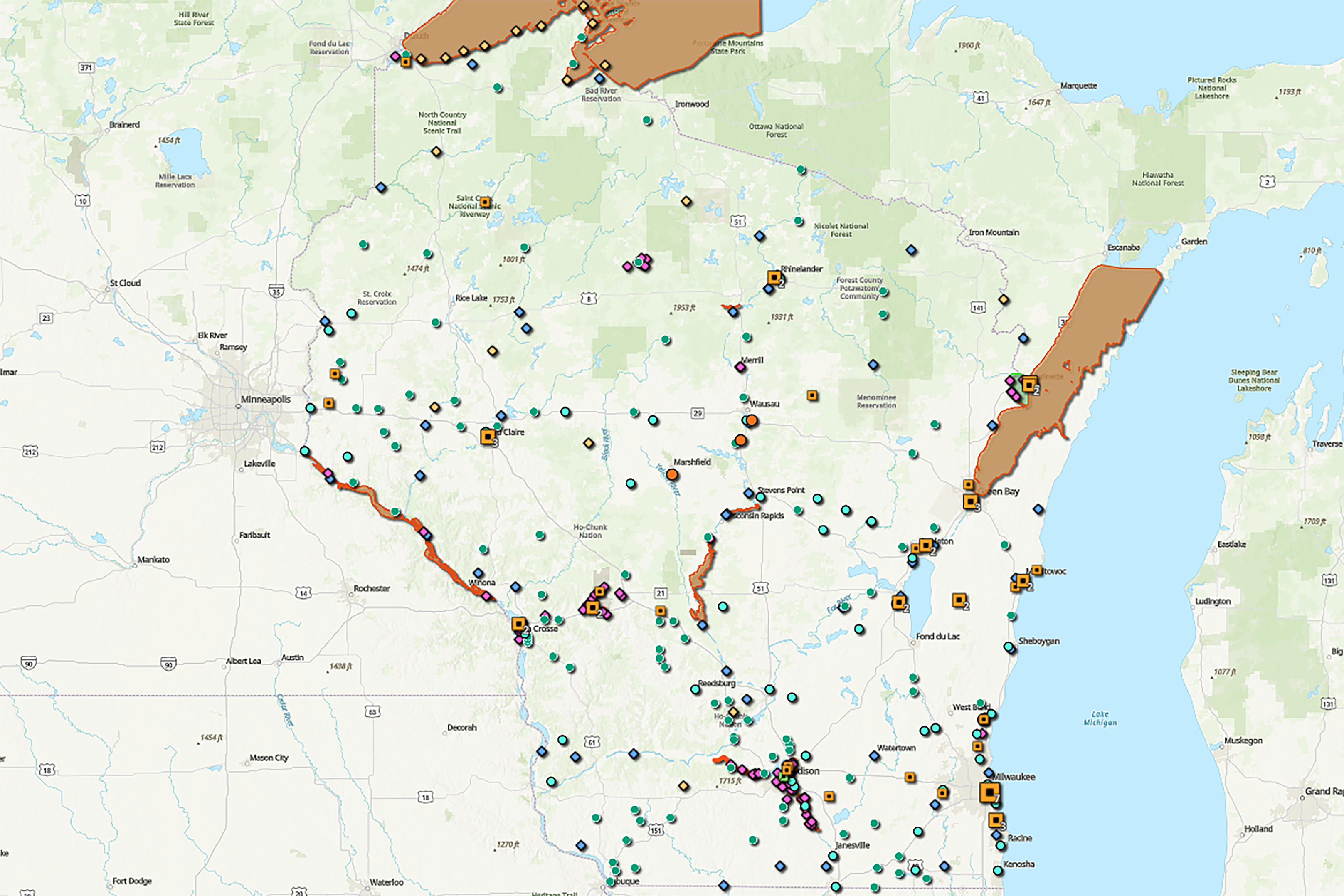

“Local communities cannot wait any longer for this vital funding and the dangerous PFAS contaminants have been identified in more than 120 communities statewide,” Hesselbein said. “So we really need to come together to try to fix this terrible problem.”

If the bill fails, is there another way the PFAS money could be spent?

If gridlock prevails, and the Republican PFAS bill fails to pass or gets vetoed, the $125 million could still get spent. But that would need approval from the Legislature’s budget committee, where Republicans hold a 12-4 majority.

The DNR has provided a breakdown to the committee of how it wants to spend the money as part of the governor’s request to release funds. Most of the money would be made available as grants to PFAS-contaminated communities, as well as provide resources to private well owners and support the public health response.

Wimberger said he thinks the committee may release funds to address PFAS if a compromise isn’t reached on the bill.

“What that would look like, I don’t know, because you’ve got Assembly and Senate members out there with their own two cents to put in,” Wimberger said.

Wimberger would have a say in that debate because he’s also a member of the budget committee. He said he wouldn’t want the $125 million to be a “blank check” for the DNR, and would prefer restrictions similar to those in his bill.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.