Lake Mendota in Madison has frozen, thawed and frozen over again this winter, and a new study — with help from a University of Wisconsin-Madison scientist — shows the consequences of less lake ice are much bigger than fewer games of pick-up hockey or a shorter ice fishing season.

Local lakes are highly sensitive to global temperatures, making lake ice one of the resources most threatened by climate change.

For the first time ever, scientists have provided an estimate of how many lakes across the Northern Hemisphere will lose ice cover and when.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Researchers found characteristics such as air temperature, lake depth, elevation and shoreline all affect its susceptibility to ice cover. Already, thanks to climate change, about 15,000 lakes that used to reliably freeze each winter are starting to miss seasons. Even under the best circumstances, in which the global community meets the target set by the Paris climate agreement, the number of lakes with intermittent freezing will likely double by the time the climate warms by 2 degrees Celsius.

“For Lake Mendota, we’re entering that period right now that it’s getting warm enough in Wisconsin at this latitude,” said John Magnuson, professor emeritus and director emeritus at the UW-Madison Center for Limnology, who was a lead author among an international group of scientists publishing the study in the journal Nature Climate Change.

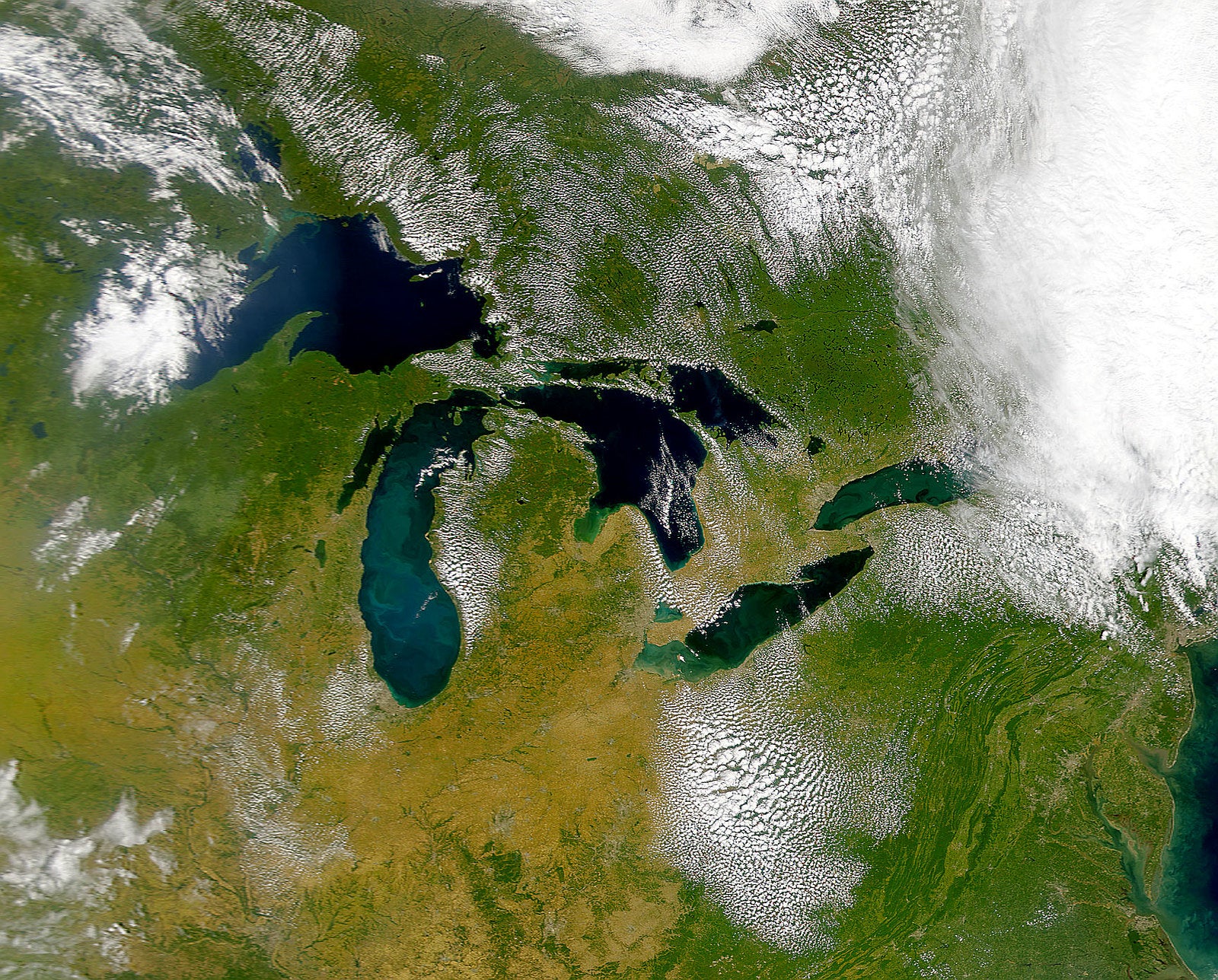

This map shows how the zone of intermittent ice moves north as the climate warms. John Magnuson/University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Limnology

Magnuson pointed to the data on Lake Mendota for the 2018-19 winter to demonstrate how the predictions are becoming a reality today.

The lake officially froze over Jan. 10, one of the latest days in the nearly 160 years it has been tracked. In all, there were only three years in which the lake froze that late, Magnuson said. He expects Lake Mendota could begin having winters where it doesn’t freeze over entirely as early as next year, or within the next five to 10 years.

“I think a lot of people would wonder, will we have ice on Lake Mendota for our grandchildren, or their grandchildren?” Magnuson said.

To be clear, Lake Mendota — and many of the lakes examined in this study — will not immediately stop freezing altogether. Instead, they will experience “intermittent” ice, meaning one year the lakes might freeze and the next it might not.

Eventually, however, the number of lakes that will experience occasional freezing and the number of intermittent ice events will rise. Some lakes might stop freezing altogether by the end of the century, according to the study.

The scientists used several climate change models to determine the possible frequency of these events more precisely.

If the global air temperature rises by 2 degrees Celsius, the goal set by the Paris climate agreement, the number of lakes experiencing intermittent ice will double to 35,300, affecting up to 394 million people who live within one hour of the shores.

In a worst-case scenario, in which greenhouse gas emissions aren’t mitigated and air temperatures jump by 8 degrees Celsius, 230,400 lakes and 656 million people in 50 countries will be impacted, according to the research. This latter case would likely push the ice-cover zone out of the United States and into northern Canada, as well as threaten the ice cover of lakes in cold Scandinavian nations.

The researchers write that the loss of lake ice is a “harbinger of permanent ice loss.”

The increasing lack of ice cover will have consequences for ecosystems and economies across the globe.

Unfrozen lakes lose more water to evaporation during the winter and warm faster during the spring, which can decrease levels of water and oxygen in the lake. These, in turn, can increase the potential for harmful algal blooms and harm fish and lake wildlife. Communities that rely on ice fishing or winter ice roads across lakes for sustenance and transportation will experience more precarious winters as well.

Unpredictable winter ice cover will also affect local tradition and activity, especially in lower Wisconsin, Magnuson said.

“People who are interested in winter recreation and ice carnivals and things of that nature will begin to find that they have to pay more attention to what the lake is doing,” Magnuson said. “Because there will be winters when we will not be able to use the lake in that way.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.