Forensic analysis has linked harmful PFAS chemicals that flowed through groundwater into Green Bay to a Marinette manufacturer of firefighting foam, according to a new study.

PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, represent a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals found in products like nonstick cookware and firefighting foam. They’ve been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines. PFAS have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down easily in the environment.

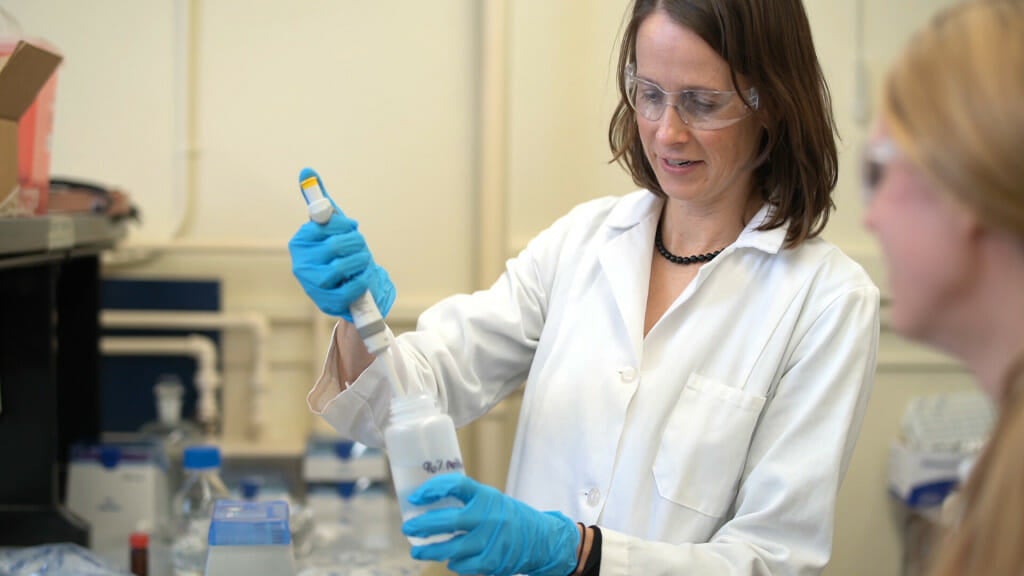

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison used a forensic approach to identify the PFAS chemical fingerprint for the aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, used by Tyco Fire Products in Marinette. Sampling of water within a ditch near Tyco’s fire training facility and along the shoreline in the bay of Green Bay on Lake Michigan showed PFAS chemicals that were identical.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Chemically, they’re really the same, so we could kind of link those two together,” Christy Remucal, the study’s lead investigator, said.

Remucal, a civil and environmental engineering professor at UW-Madison, said she and another researcher found 17 out of 26 PFAS compounds they searched for across roughly 2.5 miles or 4 kilometers of shoreline. Concentrations of the chemicals ranged up to 250 parts per trillion.

She said that’s more than 10 times higher than what you would find in Lake Michigan as a whole. It’s also more than triple Wisconsin’s drinking water standard of 70 parts per trillion. That threshold was based on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s health advisory level issued in 2016. More recently, the agency updated its advisory levels in June last year to less than zero for two of the most widely studied PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS.

“It’s really hard to contain groundwater contamination, and so that’s concerning,” Remucal said. “That’s something that we need to think about. Once PFAS are kind of out into the Great Lakes, there’s really not much you can do. You can’t treat the entire Great Lakes.”

Sarah Balgooyen, the study’s co-investigator, said the findings can help steer efforts to prevent chemicals from entering the Great Lakes and other water bodies.

“It’s much easier to test and treat water when it’s more concentrated, closer to the source, rather than downstream when it becomes really dispersed,” Balgooyen said. “I hope that this study helps people make decisions to test more for PFAS and treat it when they find it.”

In September, Tyco and its parent company Johnson Controls began operation of a groundwater extraction and treatment system that they claim will treat 95 percent of PFAS in the area. In a statement, Tyco said it welcomed research on PFAS and planned to review the study.

“Tyco has stepped up and taken responsibility, investing tens of millions of dollars to address the PFAS from our historic operations at our Fire Technology Center in Marinette,” Johnson Controls spokesperson Kathleen Cantillon said in a statement. “We have built an expansive groundwater treatment system that is already achieving thorough PFAS removal in the water treated; we have excavated soils with aggregated PFAS; and we’ve worked in partnership with neighbors to accelerate the delivery to them of their preferred long-term drinking water solutions.”

State environmental regulators have warned the treatment system will reduce, but not eliminate, the so-called forever chemicals in groundwater and surface water over the next 30 years. The DNR’s Alyssa Sellwood, a project manager overseeing PFAS contamination from Tyco, said the study’s findings underscore that AFFF from Tyco’s facility is a primary source of PFAS pollution in the area.

“Based on my read through on the study, I would say it definitely looks like a strong line of evidence that could be pursued as helping to answer some questions out there,” Sellwood said.

Questions like whether Tyco is responsible for contamination in an area that extends beyond its facility. The company and DNR have disputed whether Tyco is the source of PFAS pollution in private wells sampled in a broader area around the fire training center. Remucal said the fingerprinting method will work in some cases to identify the source of contamination, but others may prove more complex.

In March last year, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul filed a lawsuit against Tyco and Johnson Controls over their failure to report the release of PFAS from its site for years. Company officials have said they believed contamination was confined to their facility. Tyco is facing multiple lawsuits over its use of firefighting foam containing the chemicals.

The study also sampled rivers and streams near fields that received treated sewage sludge, known as biosolids. Remucal said sampling showed active ingredients from Tyco’s firefighting foam in sites near fields where biosolids from the Marinette wastewater treatment plant were spread.

Moving forward, she said the hope is to see if the fingerprinting method can be used to identify sources of PFAS contamination in other locations. Remucal is examining PFAS that builds up in foam on the surface of waters around Madison, such as Starkweather Creek and Lake Monona. She’s also working with researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey to sample tributaries of Lake Superior for PFAS across Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

‘We’re looking at tributary impacts kind of using the same idea, looking at the different types of PFAS coming in different rivers,” she said. “We’re also going to be looking at precipitation in that study as well.”

Meanwhile, Balgooyen is now working as an EPA contractor in Duluth examining PFAS in fish that have been caught on the Great Lakes and frozen over the last 40 years.

“We want to try and get a historical trend of PFAS in Great Lakes fish,” Balgooyen said.

She said researchers are starting to examine fish from Lake Superior. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources began urging anglers to limit the amount of smelt they eat from Lake Superior in 2021 after testing showed high PFAS concentrations in rainbow smelt near the Apostle Islands.

PFAS have been found in all five Great Lakes, which are a source of drinking water for roughly 40 million people.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.