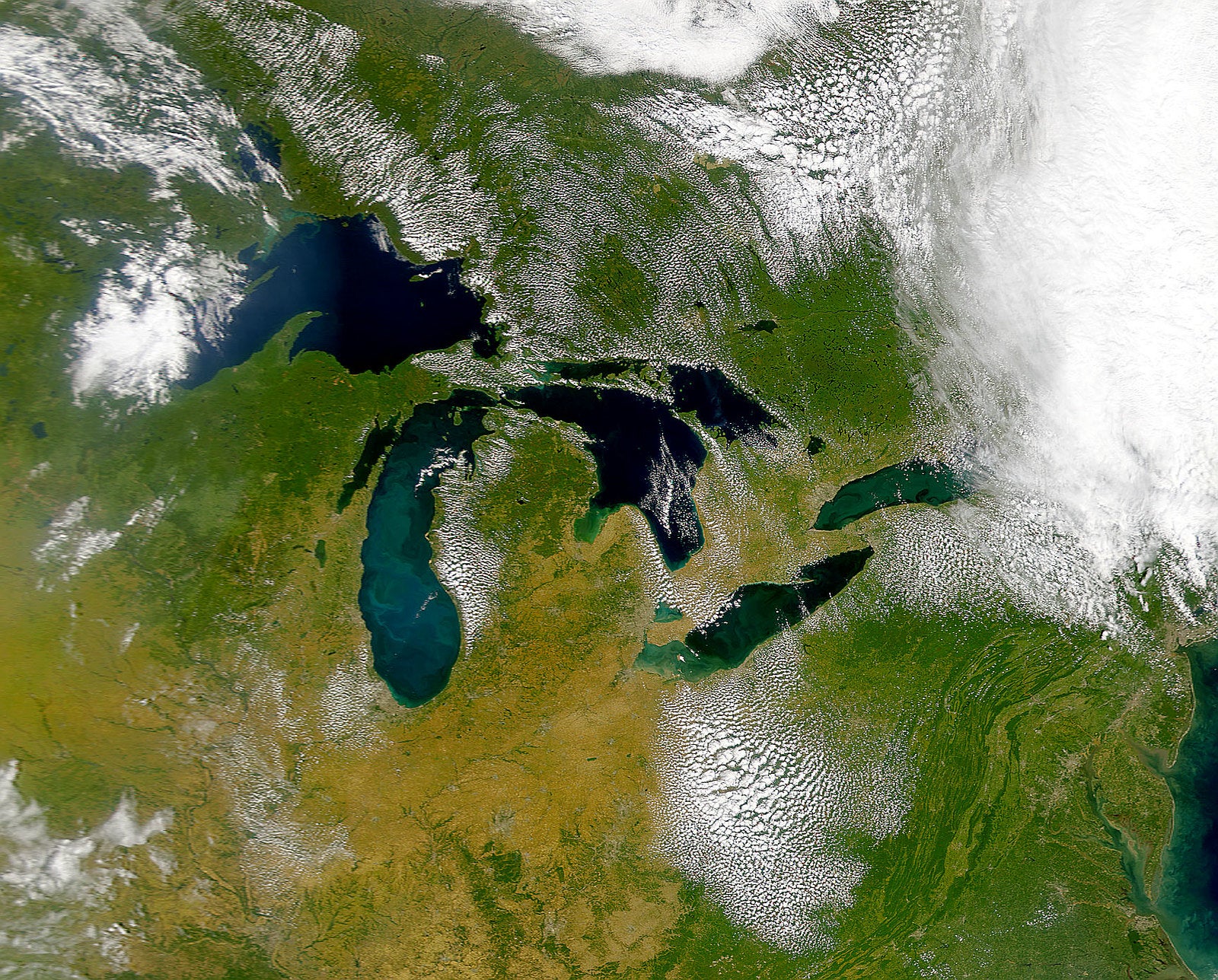

A new study on ballast water discharge has found Great Lakes ships are moving non-native species from the lower lakes to western Lake Superior. Study authors say the research provides clear evidence of the transport of organisms through ships’ ballast water tanks while the shipping industry contends more research is needed to better understand the potential impacts of their movement.

The study was conducted by the Great Waters Research Collaborative, which is a project of University of Wisconsin-Superior’s Lake Superior Research Institute. Principal investigator Allegra Cangelosi said they sampled 15 ballast water discharges from eight U.S. and Canadian lake vessels last year. Of those, 13 contained non-native species, the DNA of bloody red shrimp or both. Several species of zooplankton were detected that were previously unreported at the time of testing.

“It’s the concern that we don’t really know what happens after they’ve been discharged,” said Cangelosi. “In some cases, the condition might be right that the organism could establish and possibly push out other things that are naturally already in the environment.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She added that four discharges were examined “voyage-wide” as ships collected water for their ballast tanks in the lower lakes to their discharge in western Lake Superior. Cangelosi noted the study did not analyze whether specimens were alive or dead at the time water was taken up or discharged from ballast tanks.

The report recommends identifying best management practices and researching ballast water treatment systems for ships.

The study prompted quick reaction on Thursday from shipping and environmental groups. Tom Rayburn, director of environmental and regulatory affairs with the Lake Carriers Association, said their members would like to see more testing before any new ballast water policies are implemented. He said further study would include whether organisms were dead or alive at the time of discharge and their ability to survive in the lake.

“If we can establish more than absence and presence so we can take it to that next level of live, dead, survivability and establishment that can give us better models and also help us specifically target and eliminate those pathways through different strategies, management or treatment at that point,” said Rayburn.

The association noted they’d like to see a larger sample size to determine impacts from lake vessels. Cangelosi said the study sampled 5 to 53 percent of the water volume contained in ships’ ballast tanks that were discharged.

“That’s not much water. The thing is. in some ways. that strengthens the case that these ships are moving organisms because even though it was a relatively small portion of the relevant discharge that we analyzed, we still encountered several project-relevant non-indigenous species,” she said. “We conclude that you don’t need more evidence that they’re moving organisms. It’s clear that they are. What might be important is to know what that all means that they’re moving organisms. What’s the risk? That’s a bit harder scientifically to figure out.”

She said the difficulty in determining risks to the lake ecosystem stems from a multitude of factors that are affecting characteristics within the Great Lakes, such as climate change. Environmental groups like the Alliance for the Great Lakes contends the study is further evidence of the need for immediate action to protect lakes from invasive species.

“Today’s report confirms a common sense assumption: lakers contribute to the spread of aquatic invasive species around the Great Lakes,” said alliance President and CEO Joel Brammeier in a statement Thursday. “As such, all ships operating on the Great Lakes — oceangoing and lakers — must be accountable and stop introducing and spreading the biological pollution that is invasive species.”

The Lake Carriers Association’s Rayburn said the group has been working with regulators and researchers to prevent the spread of invasive species and develop ballast water treatment systems for ships. He noted the group commissioned a study by firms Hull and Associates and Choice Ballast Solutions in Ohio, which showed it may cost $639 million to modify the Great Lakes fleet with treatment systems. Rayburn said shoreside treatment options at Great Lakes ports may cost up to $11 billion.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.