Lucas Schulz, a pharmacy manager at UW Health, said when a patient first comes into the hospital with a bacterial infection, health care providers aren’t able to tell exactly what strain is making someone sick.

“You start antibiotics based on their syndrome, the symptoms they’re having and the most likely bacteria that are causing their infection,” Schulz said.

Once a lab is able to culture the bacteria and test whether it’s resistant to certain antibiotics, he said providers can switch to the best medication. But Schulz said treatment during the first 72 hours relies on what providers know are the most common bacteria seen in their health care system and what antibiotics that bacteria has been resistant to in the past.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That resistance is a growing problem in Wisconsin and across the country, with more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections recorded in the U.S. every year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Now, new research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison could give doctors a better understanding of which patients are affected by these strains by mapping the location of antibiotic resistance in great detail.

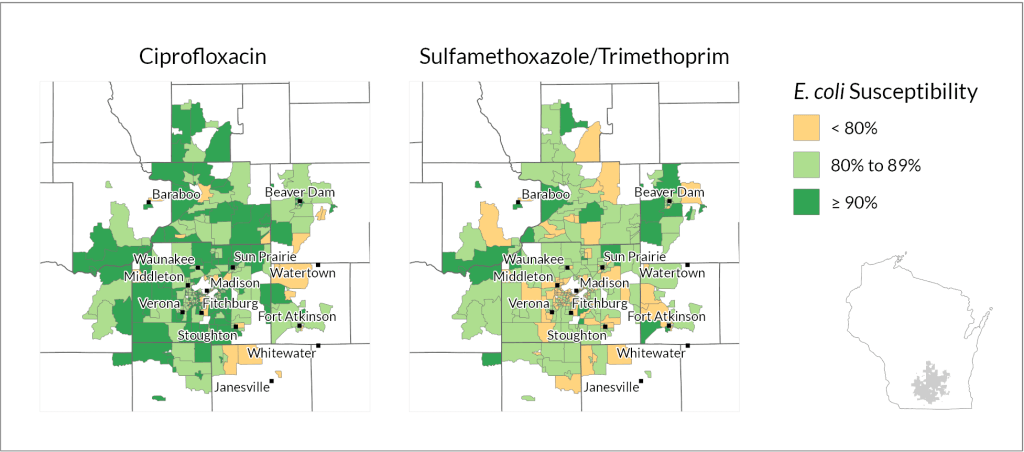

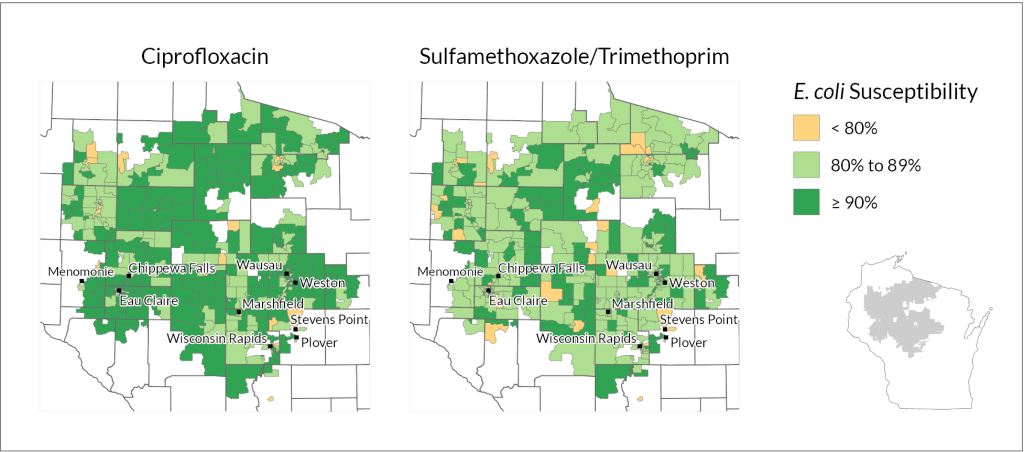

Laurel Legenza is a postdoctoral researcher at UW-Madison’s School of Pharmacy and lead author of the new study. She used data from cases of E. coli infections at three Wisconsin health care systems to map out where bacteria were susceptible to two common antibiotic treatments.

Legenza found some census block groups, which contain between 600 and 3,000 people, had much lower rates of susceptibility for certain medications, meaning more of the bacteria found in cases from that neighborhood were resistant to the antibiotic.

Legenza said the research so far isn’t able to determine why antibiotic resistance is more common in some areas. But she said the clear patterns show that finding a way to look at a patient’s location more closely could help providers make better decisions for individual cases and for the broader health care system.

“It affects individual patients’ ability to overcome an infection, but it also relates to how well we can treat infections in the future,” Legenza said. “The threat of antibiotic resistance is that in the future, we might have life-threatening infections or need surgery and we wouldn’t want to be in a situation where we don’t have antibiotics that are effective.”

She said the next phase of research will look at data like patient demographics and socioeconomic status and how those factors relate to the prevalence of antibiotic resistance.

Schulz, who coauthored the research, said it’s too early to start making care decisions at UW Health or other systems based on the results of the study. Both he and Legenza cautioned that the rates of susceptibility are based on the case data that was available from each neighborhood.

But Schulz agrees the study shows there are clear differences in antibiotic resistance based on location that are worth exploring.

“Long term, as this database grows and the ability to map this grows, it becomes a more powerful tool to consider making empiric drug choice changes,” he said.

He said UW Health has recorded a slow increase in the number of patients coming to their hospital with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Patients with these types of infections have worse outcomes, including higher mortality rates, longer hospital stays and more complications from using medication needed to treat highly-resistant bacteria. So Schulz said health care providers are motivated to find ways to improve the way they use antibiotics and identify cases where resistance is a problem early on.

Schulz said mapping resistance could also help identify how antibiotic use outside of hospitals could be contributing to the problem.

“We know that inappropriate use of antibiotics in animal husbandry and veterinary use can drive resistance development, which ultimately can impact human patients,” he said. “This is an early test to identify some of those hot zones of antibiotic resistance, which maybe we need to target with interventions aimed at changing antibiotic use outside of the health care system also.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.