Cooler nights can offer a reprieve from summertime heat.

But in Wisconsin and across the country, overnight temperatures have been warming at a faster rate than daytime temperatures.

The shift has climate scientists worried, and could increase the risks of heat stress on humans, animals and plants.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

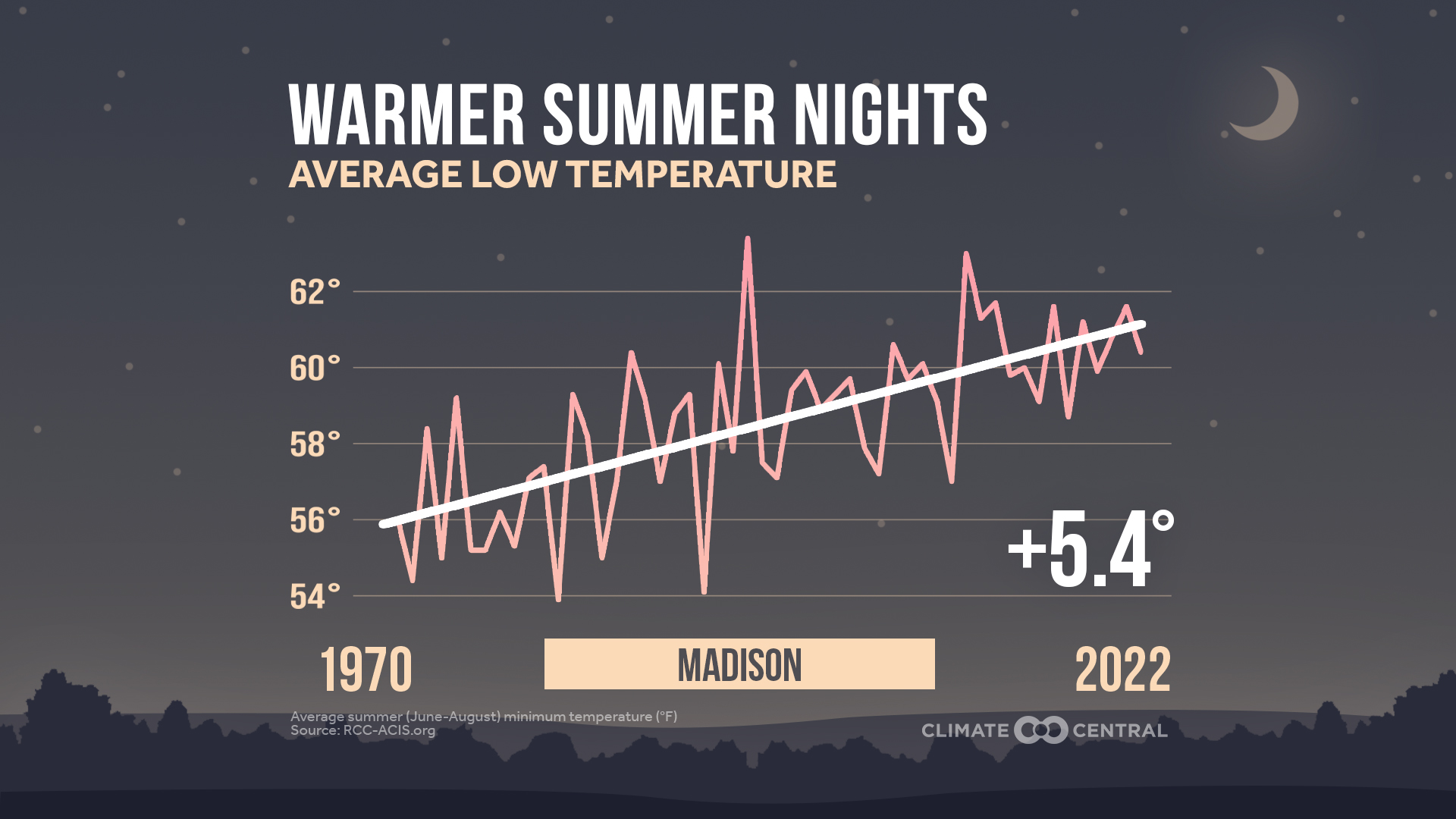

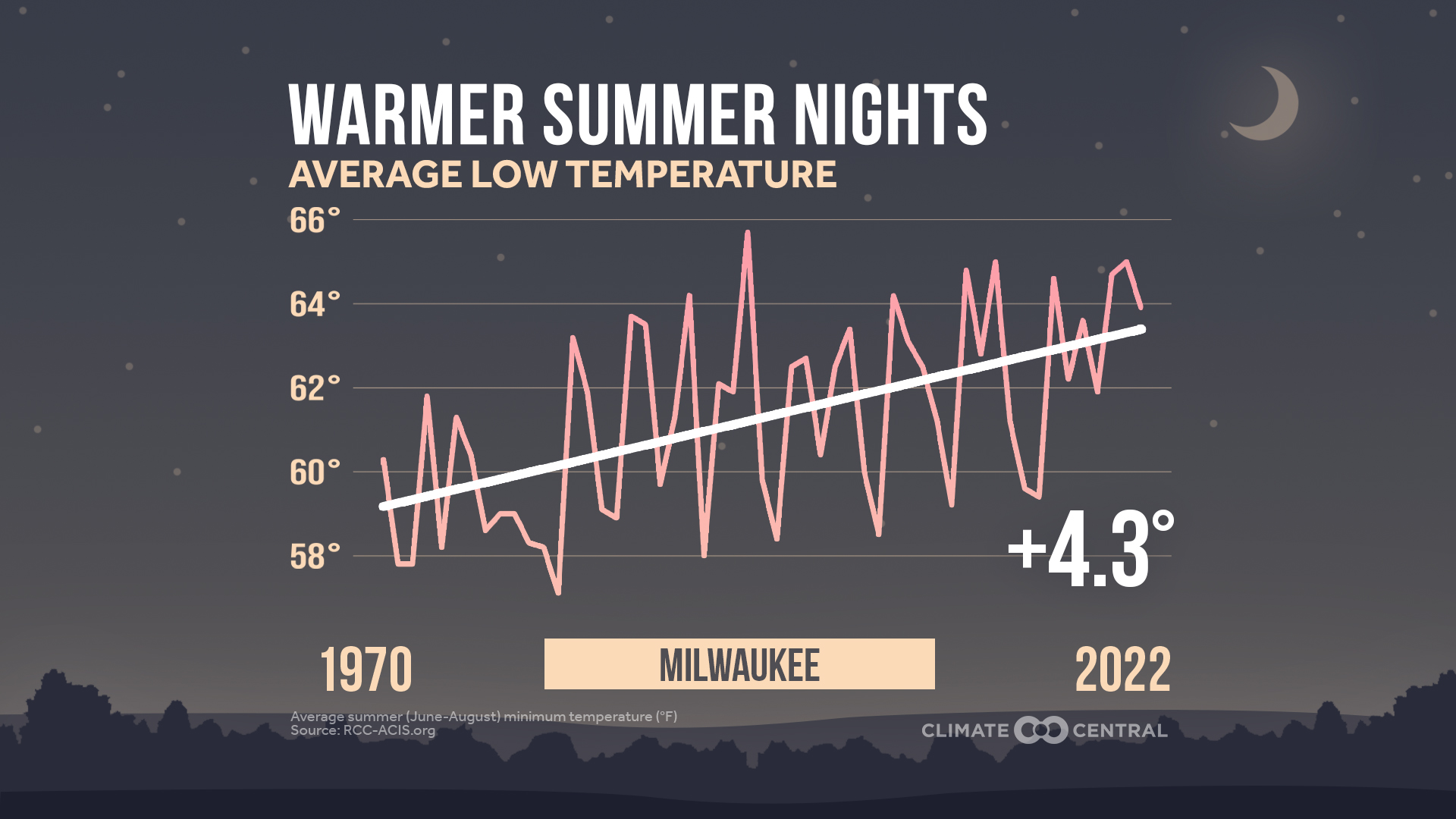

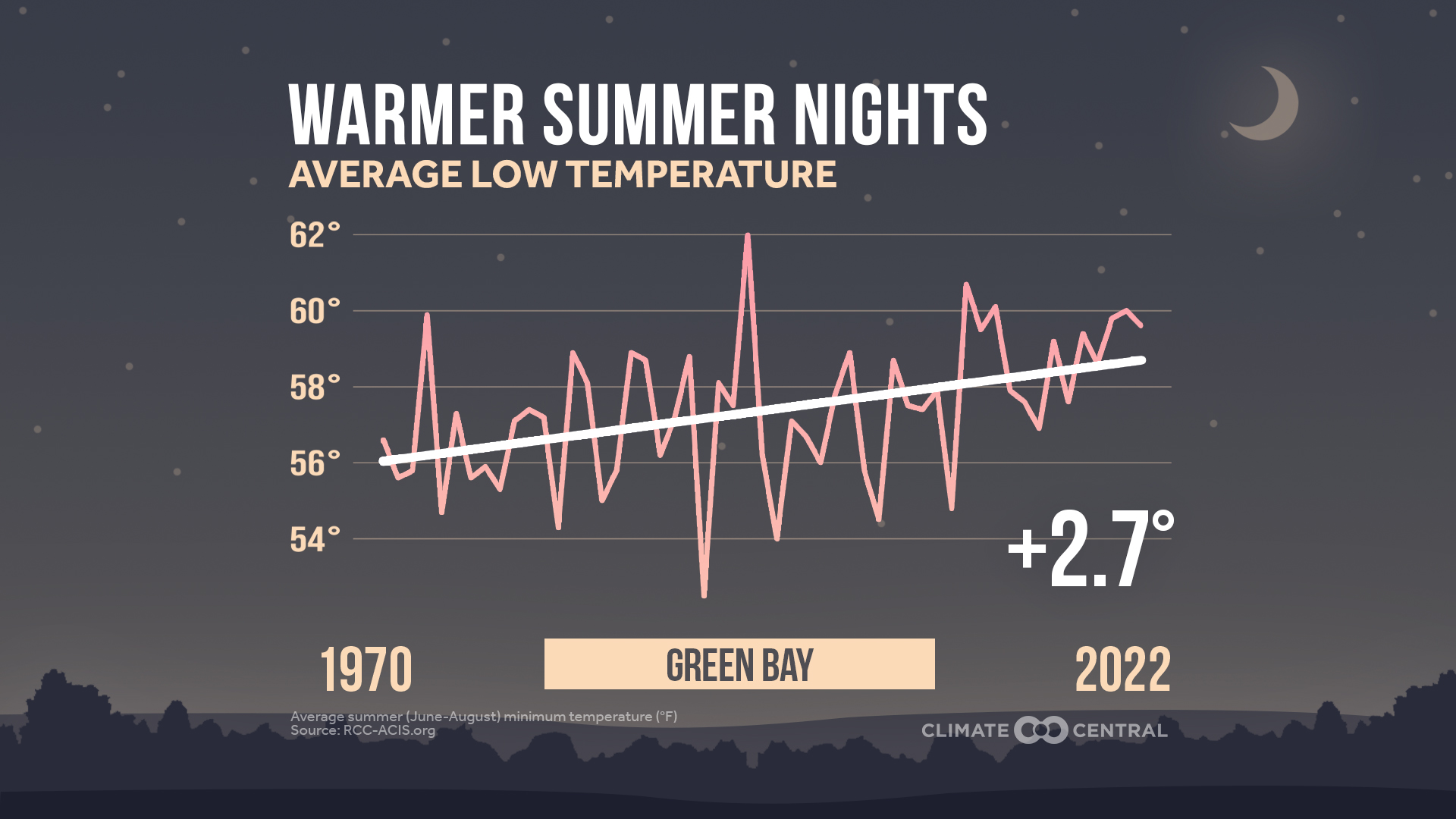

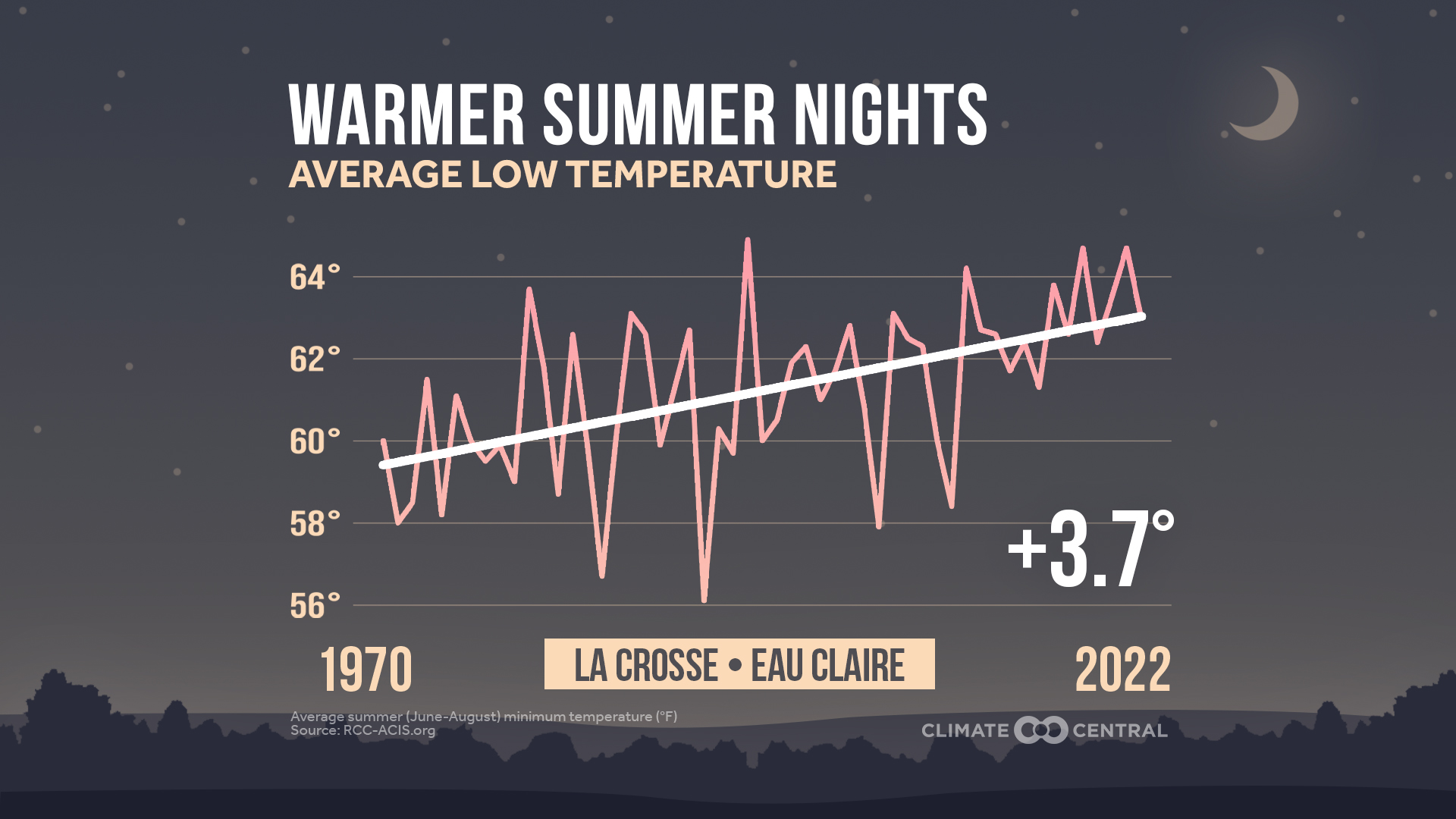

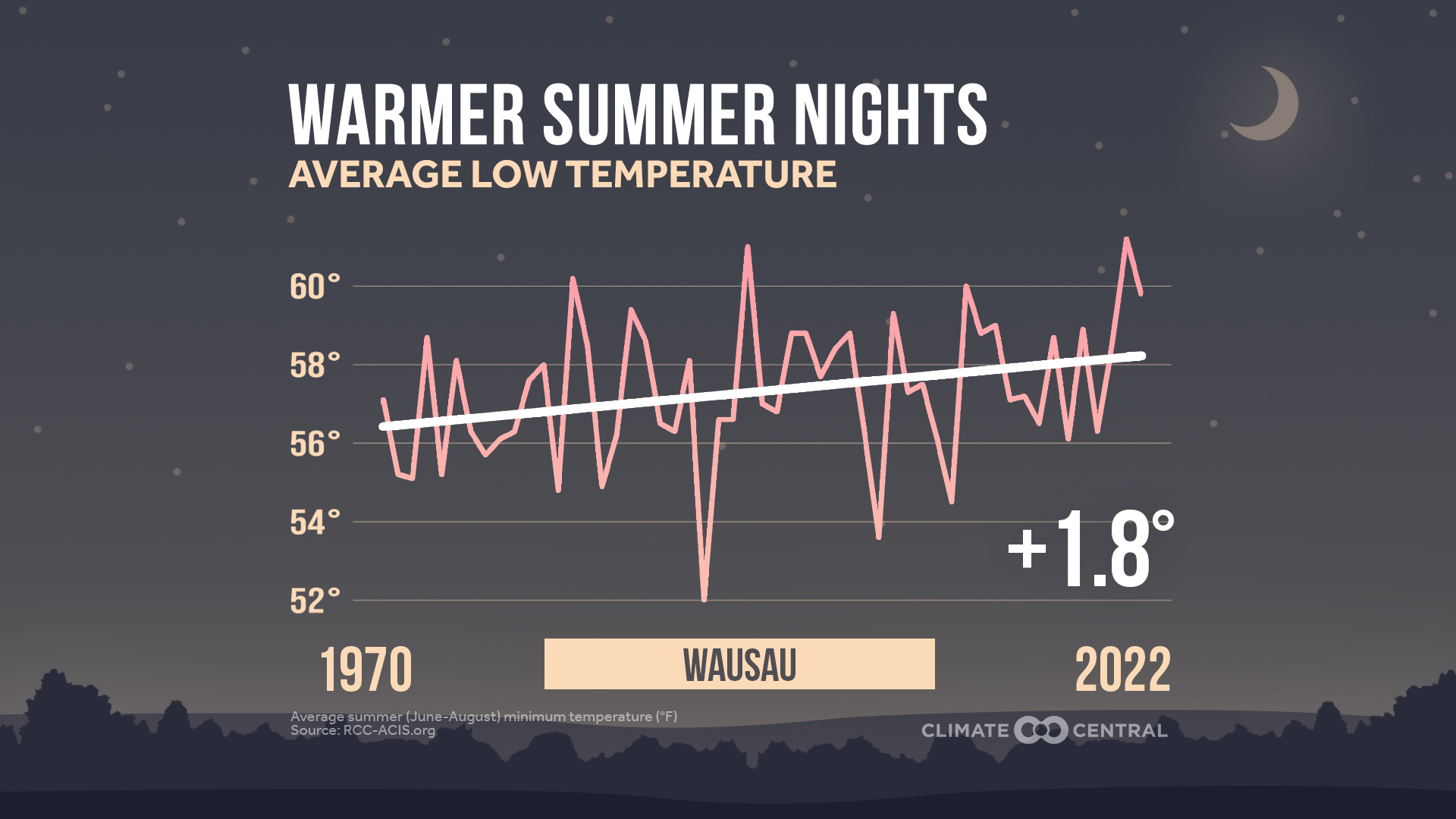

Nationally, average summertime lows have climbed 2.6 degrees Farenheit since 1970, according to the nonprofit Climate Central, which analyzed 230 locations across the U.S.

Warmer nights are just one consequence of climate change, as humans burn more fossil fuels that produce greenhouse gases, said Steve Vavrus, who leads the Wisconsin State Climatology Office.

A hotter atmosphere holds more water vapor, which in turn traps more heat, he said.

“When we have more water vapor in the atmosphere, that means the heat that would normally escape from Earth’s surface out to space at night in a dry atmosphere is less able to do so,” he said. “So it’s almost like throwing an extra blanket or two on ourselves at night.”

In Madison, average nighttime lows rose during the summer by 5.4 degrees, Climate Central found. That compares to a jump of 4.3 degrees in Milwaukee and a 2.7 degree increase in Green Bay.

Warmer nights can be especially concerning because the body no longer has a chance to cool down, said Elizabeth Berg, a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies the effect of heat in urban environments.

“If temperatures stay above a certain threshold overnight, that’s when it’s … constant stress on your system,” she said. “And that’s when things get dangerous.”

That stress on the body can lead to problems like heat stroke and heat exhaustion. Last year, Wisconsin tallied 14 heat-related deaths, according to preliminary data from the state health department.

But those deaths are “notoriously underreported,” Vavrus said, noting that extreme heat was often a factor even if it wasn’t listed on someone’s death certificate.

“If you look at the number of deaths over an average day during a heatwave, you see that the numbers are much greater,” he said.

He says extreme heat can impair judgment, making someone more likely to injure themselves if they’re working with heavy machinery.

And some Wisconsinites, including people of color and those who are elderly or low-income, are more vulnerable than others.

Outdoor workers are exposed to extreme heat for longer. So are those who live in what’s known as urban heat islands, where’s there’s less cover from heat-dissipating trees and other types of vegetation.

The heat island effect is particularly pronounced at night, Berger said.

“During the day, the sun is a bit more of an equalizer (because) so much of our temperature is dictated by what’s what’s coming down from the sun,” she said.

But at night, she noted, “a lot of the temperature is dictated by upwelling of warmth from asphalt roads, buildings, bricks — everything that was already storing heat. … So you’ll just feel a much greater difference between a single street that has a lot of greenery, versus a street that might just be asphalt and paved sidewalk.”

For people without air conditioning, options for escaping nighttime heat islands are limited, said Daniel Vimont, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at UW-Madison.

“We can go somewhere during the day like to a coffee shop, or to a cooling center or community center,” he said. “At night, we’re we’re going to be at home and trying to sleep.”

Fitful sleep can in turn exacerbate health problems, Vimont said. But unless the current trend reverses, Wisconsinites have many more warm, possibly sleepless, nights in their future.

The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts projects that, by 2060, the state will see about four times as many nights with lows above 70 degrees.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.