Though high school Advanced Placement courses are touted as a way to give teens a leg up in college, a new analysis of AP exams shows students of color and low-income students in Wisconsin score lower on the tests on average or decide not to take them at all.

Some experts say that’s because the tests aren’t designed to help all students succeed.

According to analysis by the Wisconsin Policy Forum, in the 2017-18 school year, 32 percent of all Wisconsin students who took at least one AP course didn’t take the AP exam. But that gap, said Researcher Betsy Mueller, is disproportionate.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Statewide, about 50 percent of Black students were enrolled in an AP course, but didn’t take an exam,” she said.

That’s compared to 25 percent of Asian students, 30 percent of white students and 43 percent of Hispanic students.

One reason is the heavy weight placed on AP exams, said Sheboygan Area School District Assistant Superintendent Jake Konrath.

“A lot of kids have test anxiety,” he said. “They don’t want to do the test, or they don’t feel that they’re prepared for the test.”

Unlike typical final exams, which are weighed against the whole semester, earning college credit from an AP class hinges on a single exam, which he said dissuades some students from even attempting the test.

Sheboygan schools are helping students prepare through guided study halls and tutoring, he said, and they’re moving away from the high-stakes testing classes to alternative college-level courses when possible.

And in Wisconsin, the fee for taking the test is subsidized by the state for low-income families.

Still, students of color and low-income students in Sheboygan and across the state who take the exams earn lower scores on average.

In the 2020-21 school year, 61.6 percent of students in Wisconsin scored 3 or above on their AP exam, which is considered a passing grade. White students passed at slightly above the statewide average, whereas 30.8 percent of Black students and 45.8 percent of Hispanic students scored 3 or higher.

Race, though, is just one indicator of a more complex issue, said Jon Boeckenstedt, vice provost of enrollment management at Oregon State University, who analyzes AP test data on his website.

“Students who come from families with college-educated parents, students who come from wealthier families, students who come from school districts where there’s more investment in educational and instructional items, tend to score better on the exams,” he said.

In Wisconsin, 43.6 percent of economically disadvantaged students passed their AP exams in 2020-21, compared to 64.2 percent of other students.

While the AP test is promoted as a measure of hard work, Boeckenstedt said a score depends more on the student’s starting point.

“It’s not necessarily a function of innate ability or natural talent,” he said. “It’s a matter of how much time and effort has been put into educating the student, how much support there is in the community for educational expenditures.”

Wealthier schools can send teachers to workshops and invest more resources in their students, he said, and that disparity has implications for college admissions at schools that consider AP scores in the application process.

“Sometimes the admissions process, frankly, can exacerbate inequalities in socioeconomic opportunities and racial barriers,” he said, then cited a phrase used by UW-Madison Professor Harry Brighouse, who pointed out that “there’s a difference between merit and achievement, but in America, we tend to think of those two as the same thing.”

Despite being widely spread in traditionally underserved schools, the AP program wasn’t created with underserved students in mind, said Kristin Klopfenstein, the director of the Colorado Evaluation and Action Lab at the University of Denver.

“Back in the 1950s, when the AP program really took off, it was designed for typically privileged students who were bored in the last years of high school, to give them a jump start on college,” she said.

But in the 1990s, the program expanded across the U.S, Klopfenstein said, bringing the same rigor and tests into schools with less resources.

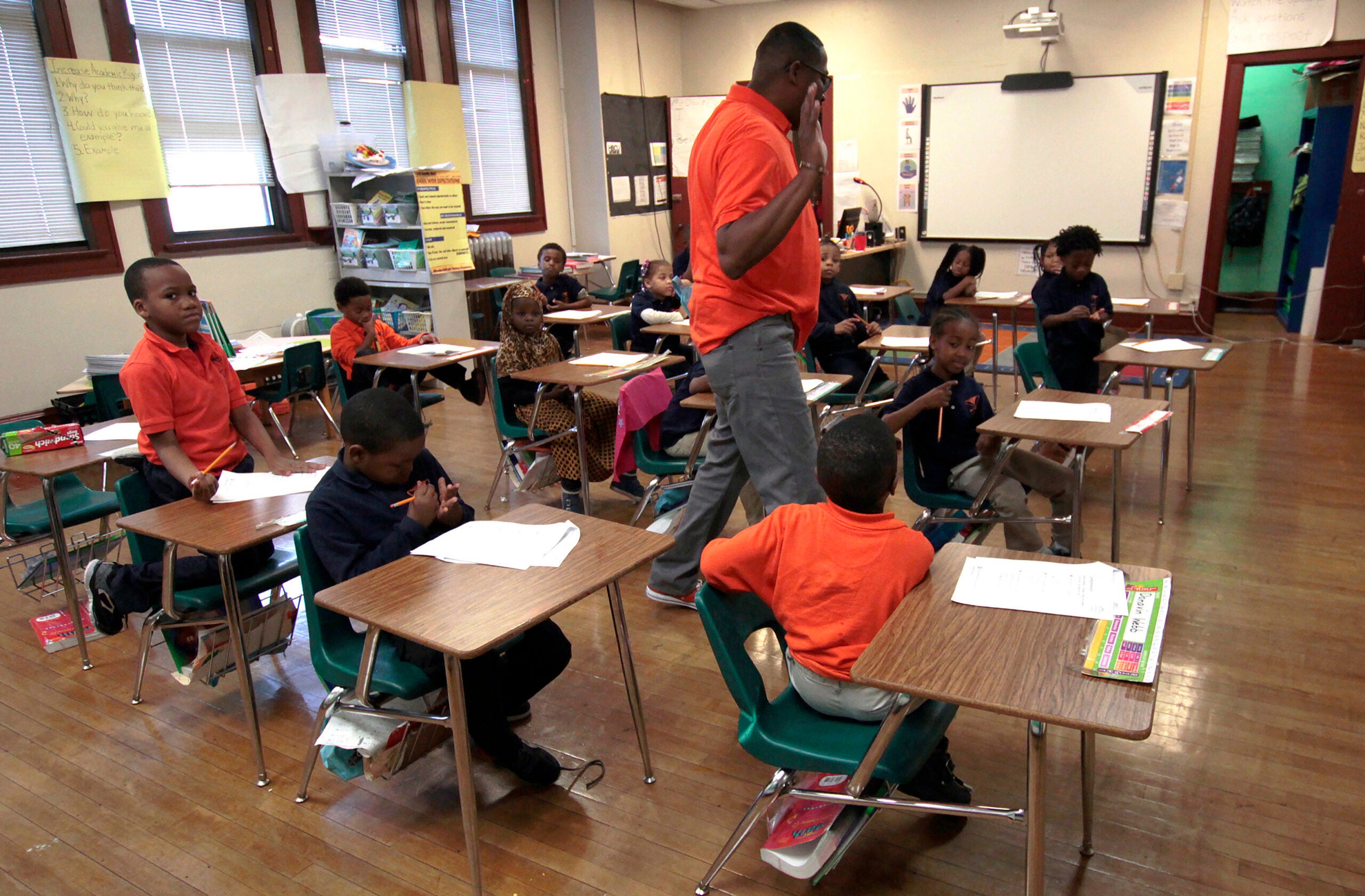

“You can’t just helicopter drop AP courses down in high schools and expect students who have had a subpar education K-8 to suddenly succeed on a college-level course,” she said. “It’s really a structural issue, where the best solution is to start improving the quality of education that traditionally underserved kids receive going all the way back to kindergarten.”

Schools are segregated across the country, Klopfenstein said, leaving low-income, high-minority students with fewer resources, despite often needing more support.

Wisconsin ranked last in the country for racial equality in education in a recent Wallethub study. The state had some of the highest gaps in standardized testing scores among students of color and their white peers. Those gaps are also seen among the share of adults with at least a high school degree.

To truly help underserved students succeed in AP courses, Klopfenstein said schools need to offer extra support, like the Advancement Via Individual Determination program. It offers separate classes devoted to helping students do well in AP classes through tutoring and building study skills.

“I’m not suggesting that these courses shouldn’t be brought in,” she said. “I’m suggesting that these courses should be brought in with wraparound support that’s necessary so that these kids actually have a shot at being successful.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.