More people in immigrant and minority communities are getting vaccinated against COVID-19 in Wisconsin. That’s in part the result of focused outreach efforts, involving places you might not expect, such as literacy classes for immigrants, and also more likely locations, like free health clinics.

The efforts are geared toward those who want the vaccine or are on the fence.

Trying to get the vaccine in the arms of people who have no interest isn’t a primary focus, says Joe Agoada, CEO of the nonprofit Sostento, which is working with nearly 100 free and charitable clinics across 15 states, including Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We’re talking about the unvaccinated but willing,” Agoada said. “We’re not looking at anti-vaxxers or folks that talk about conspiracy theories and will never have their position changed. We are looking at individuals who, because of logistical reasons, or they haven’t been approached in the right manner, have not yet gotten access to the vaccine.”

One of them is HealthNet of Rock County in Janesville where Yolanda Orosco-Arellano got vaccinated against COVID-19. Many of the clinic’s case managers and outreach workers speak Spanish, and one speaks Arabic.

Her case manager and one of the clinic’s interpreters, Alicia Alvarado, related how Orosco-Arellano wanted to get the vaccine even though she has other family and friends who are “too scared” to get a shot. Some wrongly believe a myth that getting vaccinated involves implanting a microchip, a persistent falsehood that health officials encounter.

Orosco-Arellano got the vaccine as soon as she was able, concerned her diagnosis of anemia might make her more susceptible to a bad case of COVID-19 if she were infected. Research has shown iron deficiency can weaken the immune system.

Alvarado drove Orosco-Arellano to her first dose in May.

Her three children, age 24, 21 and 12, are also protected against COVID-19, a process that began for the family in May and ended in mid-August.

The clinic’s flexible hours allowed Orosco-Arellano to get both shots without missing work as a hotel housekeeper in Janesville, where she lives after moving to Wisconsin from Oaxaca, Mexico.

For other workers, though, that can be a big barrier, says HealthNet of Rock County CEO Ian Hedges.

“Folks who come to our clinic are working labor-intensive jobs on a shift schedule. Farming. Factory work. They have a hard time missing work not only to get the shot but what happens if they get sick afterwards,” as immunity starts to kick in, Hedges said.

HealthNet of Rock County has worked with large employers like MacFarlane Pheasants in Janesville. The company made sure workers had time off and transportation to vaccination sites.

“They were incredibly proactive,” Hedges said of MacFarlane Pheasants, the largest pheasant producer in North America, according to its website.

Earlier this week, the state announced that people who haven’t gotten a COVID-19 vaccine yet can receive $100 for getting the first dose of a vaccine from an in-state provider. The money will help provide support to people who want to get vaccinated but can’t get transportation, child care or time off of work to do so, according to the governor’s office.

But time and transportation are just two factors. Equally important is trust.

“It’s not about ‘We will provide access, and they will come,’” explained Hedges. “It’s about making a true investment and having those conversations. That sounds silly, but for years health care institutions and city governments may not have been making those relationships. So when they opened up to the vaccines and wondered, ‘Why are folks not coming?’ Well, it’s because those relationships weren’t there. That trust wasn’t there.”

Statewide, nearly 42 percent of the Hispanic community is vaccinated. That’s lower than the state overall but higher than the share of Black residents who are vaccinated.

HealthNet of Rock County is one of a dozen free clinics in Wisconsin that is part of a national effort called Project Finish Line that aims to get 1 million shots into the arms of the country’s hardest-to-reach individuals by the end of the year. It’s overseen by Sostento, a New Jersey nonprofit that says it works to “alleviate public health workers’ toughest challenges so they can save more lives.”

Young, Healthy, And Now Vaccinated

Eight months after COVID-19 vaccines first became available, the protections provided against the disease remain uneven, but some racial and ethnic gaps are narrowing in Wisconsin.

While the rate of white residents getting vaccinated has dropped off, the rate of Asian, Hispanic, Native and Black residents getting vaccinated has remained higher than white residents since June, according to state data.

In absolute numbers, the share of shots given overall reflects the state’s demographics, with white residents rolling up their sleeves the most. But Asian communities now have the largest share of vaccinated people at 54 percent, the data shows.

A woman who was born in South Korea and moved to Madison learned about the vaccine in a rather unusual way: during a literacy class. In addition to teaching students English, the instructor also answered questions about the COVID-19 vaccine.

During an online education session this July, the woman, who asked to remain anonymous, relayed how she had friends who didn’t want to take the vaccine because they wanted to have a baby and were going to wait. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says pregnant women are at higher risk of severe disease if they get COVID-19 and recommends vaccination for people who are pregnant, breastfeeding, trying to get pregnant now, or might become pregnant in the future.

Another classmate explained how a co-worker did not want the vaccine but later changed her mind as more people were vaccinated. As for himself, 29-year-old Miguel Marquez initially thought he didn’t need the vaccine because he was young and healthy. But then the Venezuela native changed his mind after seeing younger people hospitalized, with some even dying.

“At that moment, I knew it’s bad. It’s actually happening. So I was worried,” said Marquez, who came to Madison in 2019.

He doesn’t understand why some people in the United States are resisting getting vaccinated when people in his homeland and other countries are begging for COVID-19 shots that are hard, if not impossible, to get.

“You can get the vaccine but in other countries they can’t. And if they can, they to pay money they don’t have,” he said.

How Successful Are Vaccine Outreach Efforts?

In April, the Madison-based Literacy Network surveyed its adult learners to find out how many were vaccinated against COVID-19 and found out less than a third were, 11 percent lower than Dane County as a whole at the time.

Time and discussions that quelled concerns helped boost the rate of vaccinated adult learners in the program to 78 percent by mid-June, said Literacy Network instructor Marie Simpson.

“Students across all of my classes were very engaged with the vaccine lessons, asked a lot of insightful questions in class, and shared their own stories very candidly,” Simpson said. “I think it says so much that when students get one of their vaccine shots, many of them proudly announce it in class. I think our lessons, delivered by trusted teachers and tutors, helped students feel comfortable making a decision about the vaccine.”

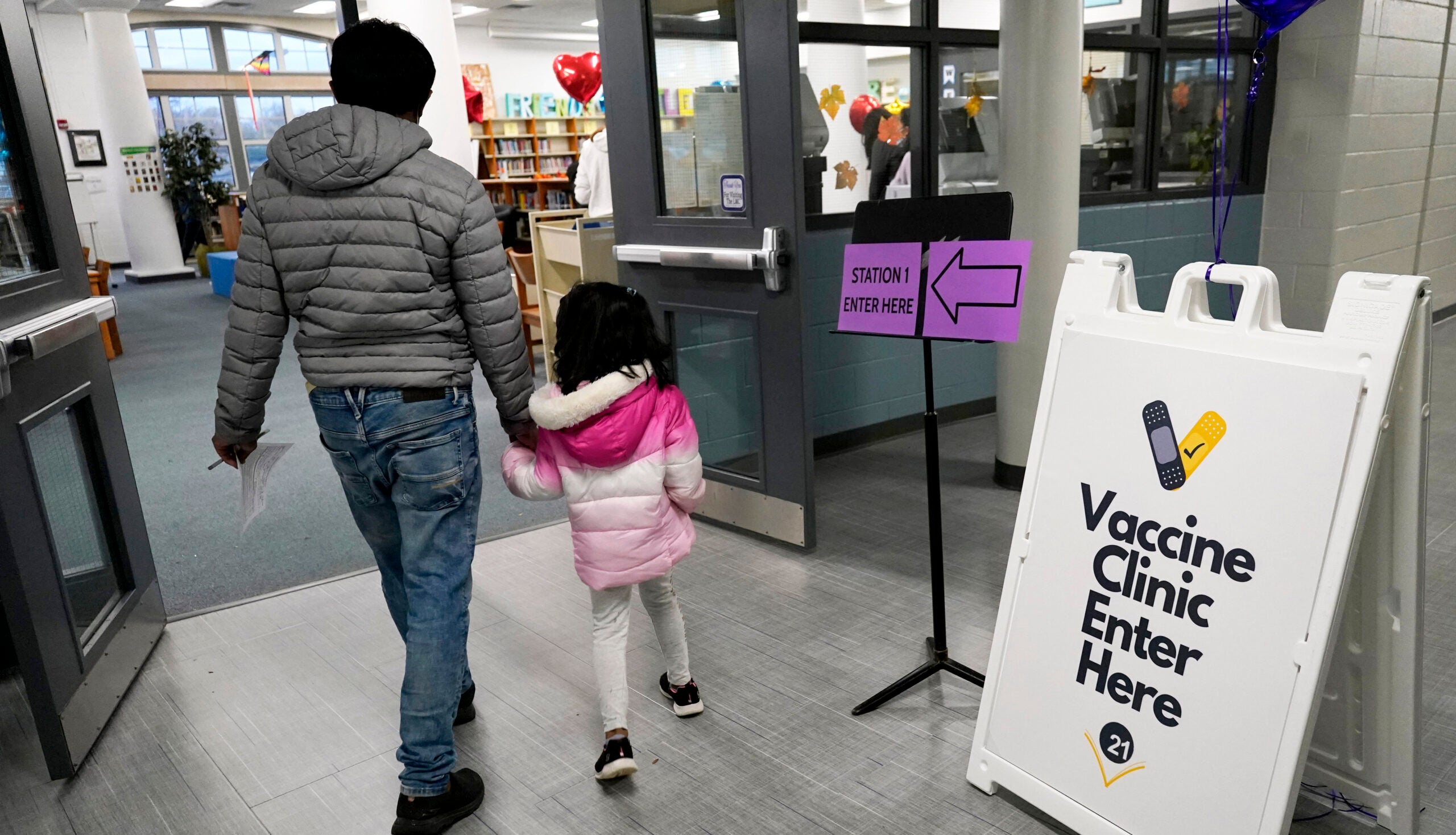

The Literacy Network not only developed vaccine lesson plans, the group created social media posts with accessible, accurate vaccine information. It also hosted two vaccine clinics in partnership with the Fitchburg Community Pharmacy.

The Literacy Network received $13,000 from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services for its vaccine outreach program.

Meanwhile, in Janesville, the free clinic HealthNet of Rock County administered more than 3,200 COVID-19 shots from February to the end of July. That’s more than some federally qualified health clinics and higher than some rural hospitals in the area, Hedges said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.