Democrats fighting the Trump campaign’s efforts to overturn Wisconsin’s election results called the lawsuit “an affront to the voters of Dane and Milwaukee Counties” and a “shocking and outrageous assault on democracy” in briefs filed Tuesday with the state Supreme Court.

But the heart of their case could rest on a much simpler argument: The president’s lawsuit was filed in the wrong place, and at the wrong time.

The Trump campaign seeks to throw out more than 220,000 absentee ballots cast in Dane and Milwaukee counties, including more than 170,000 ballots that were cast in person before Election Day.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Clerks who accepted those ballots relied on guidance handed down by the Wisconsin Elections Commission, some of which had been in place since 2011.

In a brief filed on behalf of Gov. Tony Evers, attorney Jeff Mandell argued that the time to challenge those guidelines was before the election, not after.

“President Trump chose to lie in the weeds for months nursing unasserted grievances with WEC, county, and municipal policies, and even a decision of this Court, only to spring out after the election and invoke those grievances in an effort to nullify the exercise of the right to vote by more than 200,000 Wisconsinite(s) who cast their ballots in good faith,” Mandell wrote. “Nothing could be more damaging to the exercise of a critical constitutional right than retroactively nullifying that right entirely.”

University of California-Irvine law professor Rick Hasen said state and federal courts have typically respected what’s known as the “laches” principle when it comes to election disputes.

Put simply, “laches” prevents parties from retroactively bringing lawsuits for issues that could have been disputed ahead of time.

“I think courts have shown themselves properly to be very skeptical of arguments that voters should be disenfranchised because of a potential problem that could have been called to the attention of the courts well before the election but wasn’t,” Hasen said.

In Wisconsin, Trump is challenging four categories of absentee voters in Dane and Milwaukee counties.

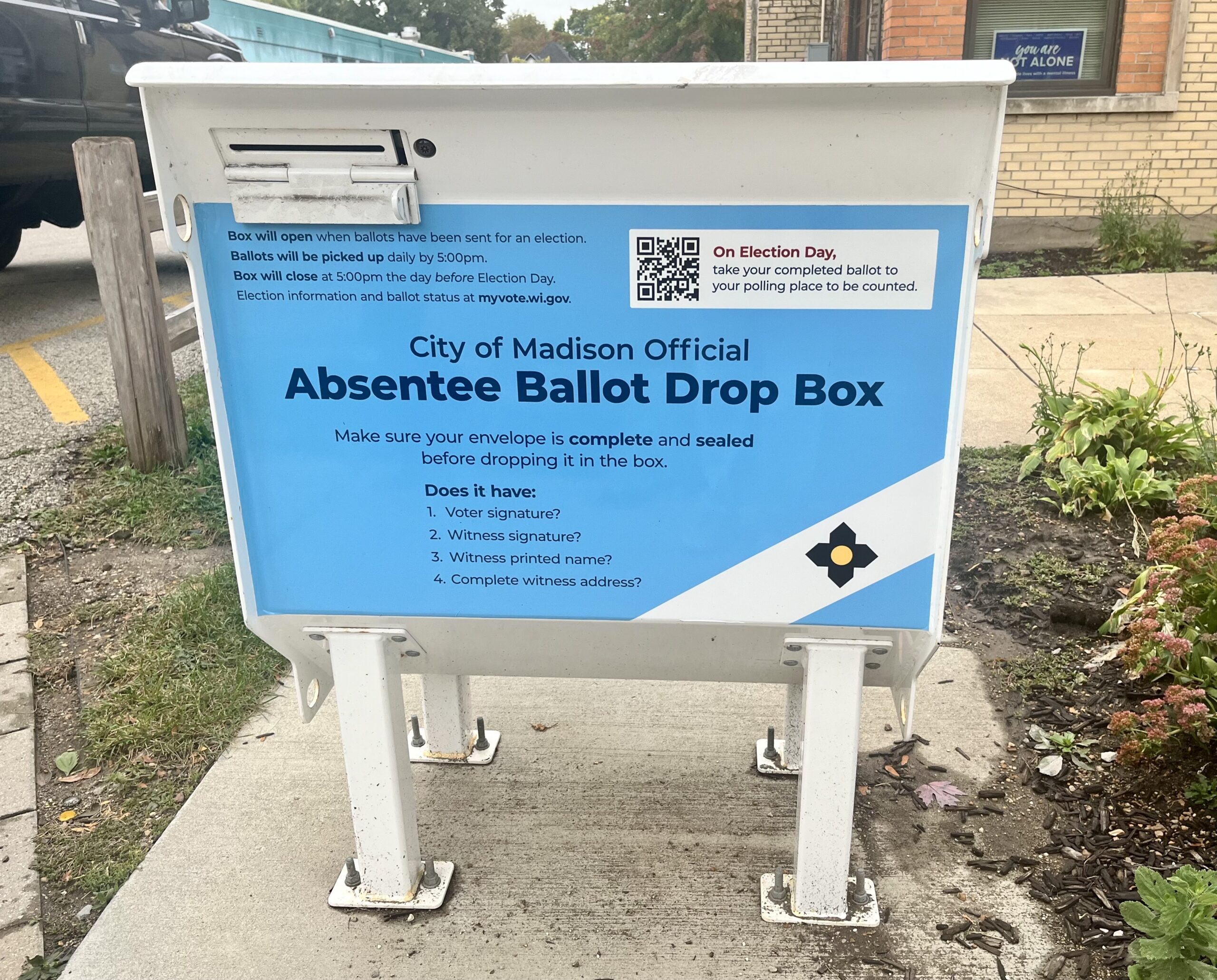

His campaign wants to reject the more than 170,000 ballots cast in person before Election Day on the grounds that voters did not fill out written applications. The Wisconsin Elections Commission has said for years that a separate application is not necessary when voting in-person absentee.

Trump’s campaign is also challenging about 5,500 ballots where clerks completed a witness’ address, which is also allowed under Wisconsin Election Commission guidance.

The campaign is challenging another 28,000 ballots from voters who said they were indefinitely confined. Democrats argue those ballots were cast using guidance from the WEC that was informed by a state Supreme Court ruling earlier this year.

Another 17,000 votes challenged by Trump were absentee ballots collected at “Democracy in the Park” events sponsored by the city of Madison earlier this year. Republicans raised concerns about those events before they were held but never challenged them in court.

Hasen said the problem with challenging those votes now and not before the election is that it punishes voters who did nothing wrong.

“Voters proceeded under the rules that they were given,” Hasen said. “Voters assumed that what they were doing was legal and there’s both federal and Wisconsin authority that says you don’t disenfranchise voters for a fault of someone else.”

While the Wisconsin Supreme Court isn’t bound by precedent set in other states, Hasen noted that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court had rejected one of Trump’s lawsuits, partly on the grounds that it was filed too late.

One of the other arguments from Evers and Democrats is that Trump’s lawsuit should have been filed with a lower court first.

Trump’s lawsuit was filed with the Supreme Court through what’s known as a petition for original action, a process that used to be rare but has become common in recent years under the court’s conservative majority.

Unlike other lawsuits that start at the county, or circuit court level, an original action lets parties bypass the usual appeals process.

What’s different in this case is that Wisconsin’s recount law specifically requires lawsuits to start in circuit court.

“Courts have a duty to follow the plain language of the statute and cannot simply overlook it,” argued Evers’ brief. “The plain language of the statute is unambiguous.”

In addition to Evers, lawyers for the Democratic National Committee and the Wisconsin Elections Commission filed briefs with the Wisconsin Supreme Court Tuesday. So did lawyers for Dane and Milwaukee counties.

The court could rule on the case at any time, but the clock is ticking. Wisconsin’s presidential electors are scheduled to meet to finalize the state’s election on Dec. 14.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.