The first illness that Jennifer Hebl’s now 9-month-old daughter Emelia ever got was COVID-19.

“There was one day where I was just sitting with her in my room. She was crying, you could tell she was feeling just terrible, and I started crying with her because this is the only way we can really communicate — she can’t tell me how she’s doing other than crying,” Hebl said. “It was just really hard to see that and not be able to do anything about it.”

Jennifer, her husband and Emelia all got sick in April, after her husband returned from a trip to New York. He’d traveled before during the pandemic, and they’d been extra cautious about isolating when he returned.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We’ve been very, very cautious through this whole thing. We really don’t go anywhere, we do things outside, we make people wear masks around Emelia,” she said. “This time, we kind of let our guard down, thinking that numbers were low, and we got very unlucky and we all got it.”

The family made it through without hospitalizations, though Hebl said there was a terrifying period when Emelia had a fever of nearly 103 degrees, and she was on the phone with an after-hours nurse weighing whether her baby needed emergency care.

After the omicron wave of cases in the winter subsided and mask mandates around the state dropped, many families resumed more of their pre-pandemic activities, often without masks.

“I think in the beginning, we really protected children, because we didn’t know, and they were very isolated. And then we saw the adverse consequences of the isolation,” said Dr. Laura Cassidy, an epidemiologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “I think it all blends together — that if people aren’t taking as many preventive measures as they were, children are interacting more and the strains are more contagious, then it’s more likely that kids will get sick.”

According to state Department of Health Services data, cases of COVID-19 are relatively low now, compared to the omicron-driven peak and the wave of delta variant cases around the start of the school year. However, experts caution that state case numbers are a very limited picture, as at-home tests have become more widely available, and many people have ceased testing altogether. Community levels — calculated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention based on the number of cases and hospital capacity in a community — are low in most Wisconsin counties, medium in 20 counties and high in 11 counties.

“Reporting has been so hit or miss, as far as people not testing, or maybe they’re just home testing and not being reported,” said Dr. Amy Falk, a Wisconsin Rapids pediatrician who also headed a study that showed school COVID-19 spread was low with proper masking and distancing. “We’re kind of winding into whatever this next (pandemic) phase is, and we may not know what true incidence is.”

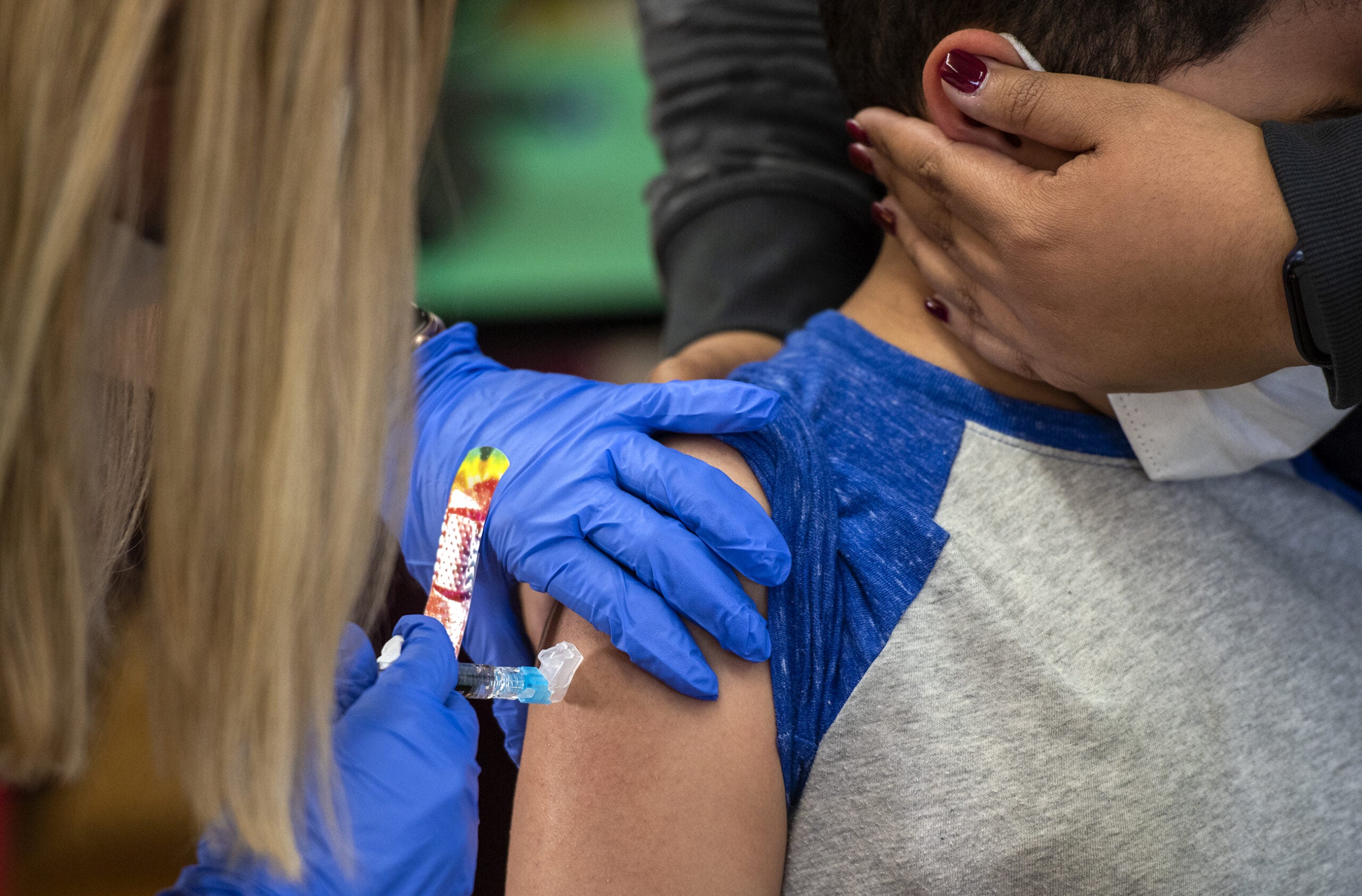

Falk’s children got COVID-19 about six weeks ago and passed it on to her. The older two, ages 5 and 8, had been vaccinated, but her 2-year-old is still too young. Fortunately, everyone’s cases were mild; she said they may not have noticed if Falk hadn’t been testing for work.

Children under 5, like all age groups in Wisconsin, saw a spike in positive cases of COVID-19 that peaked around May 8. Unlike the other age groups, though, the youngest Wisconsinites aren’t yet eligible for a vaccine — though the White House said last week that children under 5 may be able to get their vaccines beginning June 21.

“My 2-year-old will get it when it’s approved. I don’t have any qualms about it, truly. It’s had great safety profiles in those older kids and it’s an even lower-dose, and I think it can overall help provide another level of protection,” said Falk. “If they do get it, they’ll be less symptomatic, so that’s good. They’ll feel better faster, most likely, because their immune system will jump on it, and they won’t end up in the hospital or dead.”

For families whose kids under 5 just got sick, it can be frustrating to know the vaccine that could have added a layer of protection against severe illness is coming too late to shield their little ones from several miserable days of fatigue, pain and fever — or worse.

Hebl said that now that they made it through Emelia’s first illness, she’s glad a COVID-19 vaccine will be available soon to protect her. Infection-based immunity from the more recently circulating COVID-19 strains has shown signs of waning more quickly than previous ones. She said they’re still a little worried about symptoms of long COVID, which is believed to have lower incidence in children but may be as high as 1 in 4 among symptomatically infected kids.

“The one thing we really don’t know yet is what the long-term effects of COVID are in children,” said Cassidy, the epidemiologist. “That’s one of the long-term concerns.”

Cassidy and Falk say overall rates of illness in children — and adults — are up, especially as masking is down. Falk’s pediatric practice in Wisconsin Rapids has had a steady wave of infections, some from COVID-19 and some from other respiratory illnesses like the flu and respiratory syncytial virus that resurged this year after a quiet 2020.

“Usually, early summer is a fairly lull time, but I’ve been booked every day. Our number of walk-ins is high and there’s a high level of child illness,” Falk said.

Families whose youngest children are showing symptoms of COVID-19 are also dealing with that after two years of quarantines, day care closures and school shutdowns have eaten up their sick and vacation time – if they had any to begin with – and tested the limits of employers’ willingness to be flexible.

“I have a lot of families — and I get it, practically speaking — they’re like, ‘We can’t have you test them today because I cannot miss work,’ and they decline testing,” said Falk. “It’s like, ‘I will lose my job and there’s no more COVID forgiveness if we end up having to have them out and it runs through our family.’ It’s one of those reality versus the textbook answer things.”

Hebl said that among her circle of friends who have been similarly careful throughout the pandemic, she’s heard of more testing positive than at any other point during the past two years.

“It is no fun seeing your baby sick ever, but especially for the first time. We had her sleep in our room every night that she was sick just so we could make sure she was breathing OK,” she said. “I wish people would take that more seriously — that they’re not vaccinated, and just because you’re not afraid of it doesn’t mean us with kiddos that can’t be vaccinated aren’t terrified.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.