Across the state, policies in county jails have prevented thousands of people within their walls from voting, according to a new ACLU Wisconsin report.

“Widespread variance across voting policies, practices, and protocols within Wisconsin county jails has led to the continued disenfranchisement of eligible voters that are within the jails of Wisconsin,” said Abby Kanyer, the organization’s deputy director of community engagement.

Among the roughly 13,000 people in Wisconsin jails on a given day, most are eligible to vote, the report said. That includes those who are awaiting trial or serving sentences for misdemeanors. But according to the report, only 50 people voted from jail in the 2020 elections.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Some jails said it’s the inmate’s responsibility to start the process of voting, the report said, including in the Racine County jail.

According to the report, Racine County jail administrators said, “It is 100 percent on the inmate to facilitate this in a timely manner.”

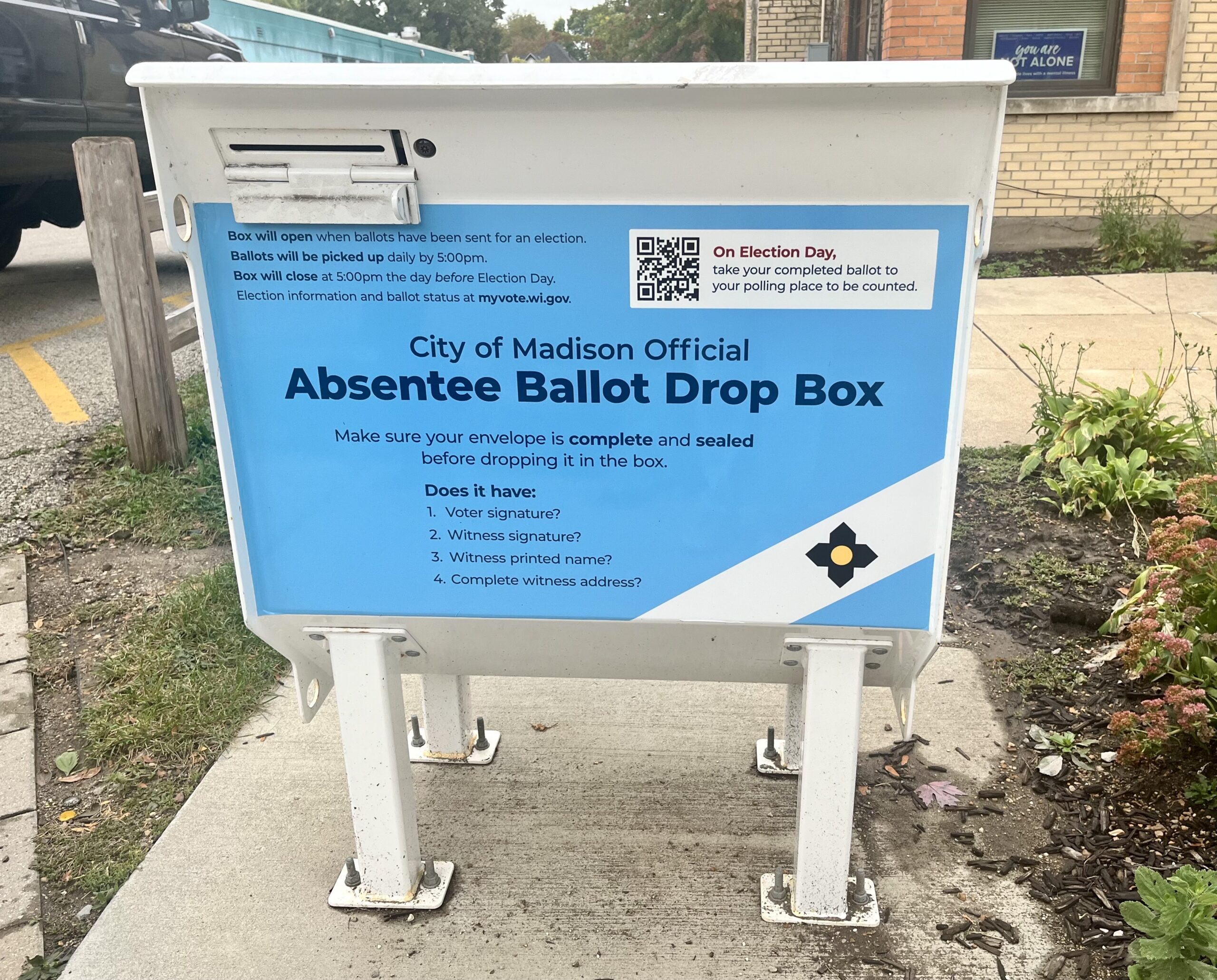

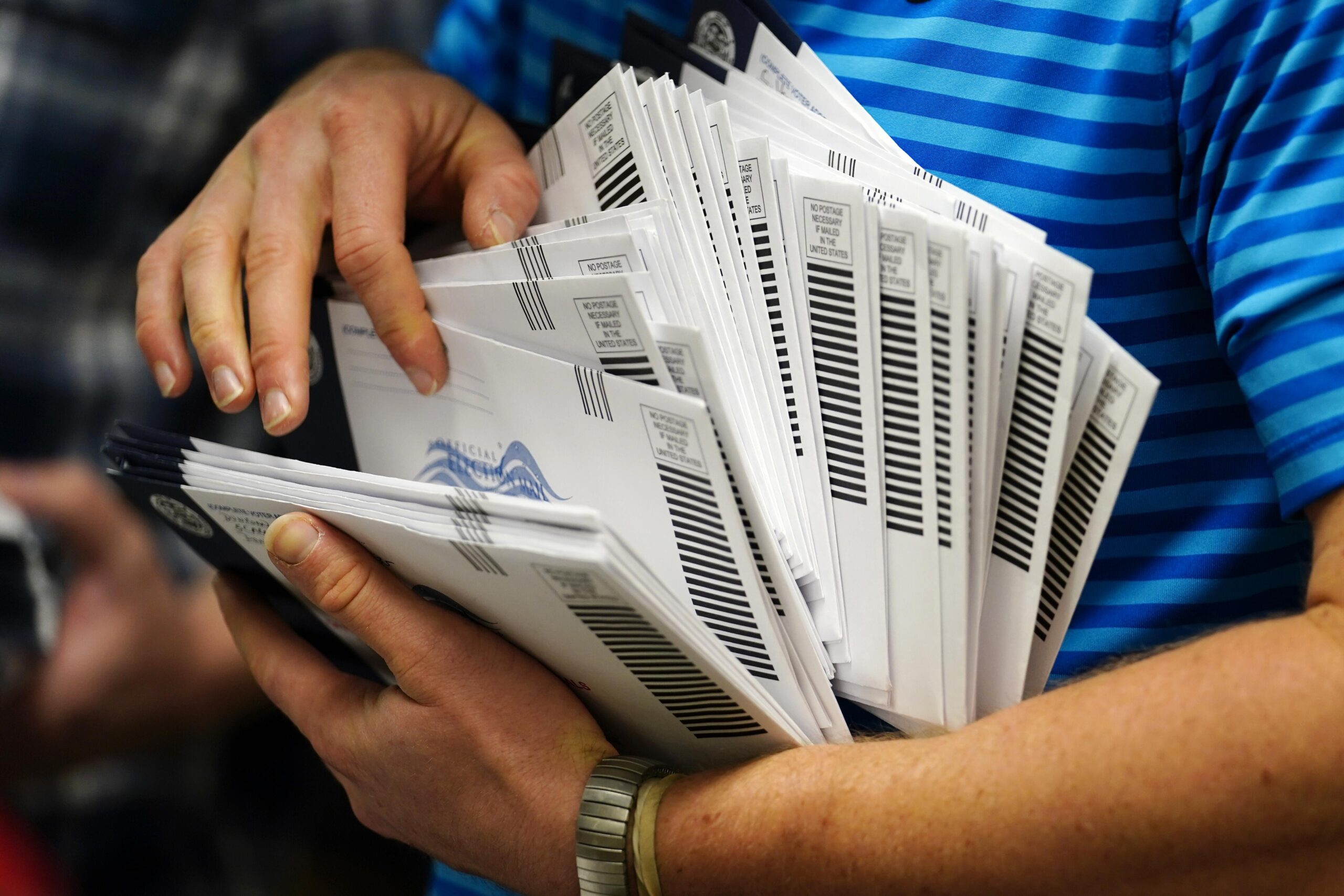

At the jail, the report said, each inmate must fill out their own absentee ballot and pay to mail it, unless they are indigent, but no outside organization can come into the jail to give inmates their ballots or register them to vote.

Lt. Michael Luell of the Racine County Sheriff’s Office confirmed that is their policy, but he said it’s in line with the law.

Luell said the jail gives eligible inmates opportunities to register to vote, get a ballot and vote absentee. He also said the sheriff’s office provides inmates with computer tablets and instructions for absentee voting.

“While the Sheriff’s Office will not allow outside groups within the jail for security reasons, inmates are allowed contact with a wide range of people/professionals, resources, and legal material,” he said.

The Wisconsin Sheriffs and Deputy Sheriffs Association did not respond to a request for comment.

But policies like those at Racine County operate under the assumption that people in jail understand how the process works, according to the report.

“There’s a lack of knowledge or clear information about eligibility and criminal disenfranchisement laws,” Kanyer said, “as well as…a lack of information from an educational perspective on how to register to vote while in jail, how to understand timing and the return of crucial pieces of registration material.”

Around 20 percent of counties have “robust, highly detailed” protocols, Kanyer said. Around 44 percent of counties have short policies with vague language, the report said, and roughly 22 percent have no written policies.

A slew of other barriers also get in the way of people’s ability to vote, according to Shauntay Nelson, the co-director of states at All Voting is Local.

To register in Wisconsin, voters need to show a valid ID, she said, but not all people in jail have access to their ID.

People in jail also can’t go to the polls, Nelson said, so they have to request absentee ballots, which creates an extra challenge, because if they send it to one jail, but they’re transferred to another, the ballot transfer doesn’t follow them.

But these barriers don’t impact communities evenly, Nelson said.

“We all know that…the communities that are jailed more are predominantly communities of color,” Nelson said.

According to the report, Wisconsin has the second-highest ratio of Black to white incarceration, and Native Americans in the state are jailed at seven times the rate of white Wisconsinites.

Low-income people are also jailed at a higher rate, the report said, and the cash bail system keeps people with fewer resources in jails longer.

“This further alienates these communities from the political process, and increases the numbers of individuals who have and can lose their faith in our democracy,” Nelson said.

Right now, she said, the issue is especially relevant.

“Unless we take the necessary steps now to ensure that jails make registration and voting accessible to eligible people, we’re looking at thousands of folks who may not be able to have their voices be heard in less than three weeks,” Nelson said.

Solving the problem, Nelson said, starts with getting jails to write clear guidelines, so that officials have a documented procedure that stays in place even after turnover.

“We are responsible as citizens of Wisconsin to participate in the democratic process,” Nelson said, “and when some are hindered from participating in that process…it impacts our ability to hear the voices of the people of Wisconsin.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.