This November, something will happen that Wisconsin politicians and advocates have been fighting over for more than a decade: the state will host its first major election with a voter ID requirement in place.

Wisconsin voters will also be able to participate in the earliest and most extensive in-person absentee voting the state has ever seen.

While this won’t be the first test of the state’s new voter ID law, turnout in other elections typically pales in comparison to what Wisconsin sees in presidential races. In 2012, for example, roughly 70 percent of eligible Wisconsin voters cast ballots in the race for president, which was among the highest turnout in the country. As many as a million voters could encounter Wisconsin’s photo ID requirement for the first time.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The evolution of Wisconsin’s voter ID law from 2011 until today is a vastly complicated series of court challenges, appeals and decisions. The same can be said of early voting. In both instances, courts shaped the laws as they’re known today.

As days of early voting tick by and the general election draws nearer, it seems an appropriate, and perhaps essential time to retrace the evolution of the law in Wisconsin, from the very beginning.

Interactive timeline by Scott Gordon, Shawn Johnson and Laurel White

2011 – The Law Is Signed, Lawsuits Are Filed

When Republicans take control of state government in the GOP wave election of 2010, there’s little doubt they’ll pass a voter ID law. After all, they’d tried and failed repeatedly under Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle, who vetoed one voter ID bill in 2003 and two more in 2005.

But nobody knows how strict the latest version will be until Republicans start discussing the details in 2011.

“This version of the bill is more restrictive than any bill we’ve had in the past,” warns David Canon, a University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor, at a public hearing on the state Senate’s version of the bill in January 2011. “Indeed, if this bill passes, it would be the most restrictive in the United States.”

The bill undergoes changes before it’s ultimately passed by the legislature in May 2011, but election observers say the final product makes it more challenging for poor people, senior citizens, and students to vote in Wisconsin. It lets people get a free, state-issued ID for voting if they don’t have one, but in some cases, residents must first secure another document, like a birth certificate. The new law is silent on what to do if people can’t get those documents, or can’t afford them. The law also requires for the first time that people live at a Wisconsin residence for 28 days before they can vote there.

Gov. Scott Walker signs the voter ID law on May 25, 2011, telling reporters there’s no excuse not to have a photo ID.

“We need it for public assistance, we need it for just about everything else in life,” Walker says at his Madison signing ceremony. “This is a logical requirement.”

Asked whether the law will survive a legal challenge, Walker doesn’t flinch.

“Absolutely, I have no doubt about it,” he says.

Just a few months later, groups that oppose voter ID start to take action.

The Wisconsin League of Women Voters files the first lawsuit in Dane County Circuit Court on Oct. 20, 2011, arguing in its complaint that voter ID violates the state constitution. The league’s reasoning? The constitution lets the state ban felons from voting, but it says nothing about excluding voters who don’t have IDs. Compared to other lawsuits that will follow, this one is short and straightforward, asking the court to declare Wisconsin’s photo ID requirement unconstitutional on its face.

The ACLU files its lawsuit next on Dec. 13, 2011 in federal court, marking the beginning of the Frank v. Walker lawsuit, which continues today. It’s named for Ruthelle Frank, who is 84 years old in December 2011. The ACLU’s complaint states that Frank has voted in every Wisconsin election since 1948, but she lacks the necessary identification to vote in Wisconsin under the new photo ID requirement.

A few days later on Dec. 16, 2011 the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP files its lawsuit, and like the League of Women Voters case, this one is also in Dane County Circuit Court. But while the league’s lawsuit is a fairly simple challenge, the NAACP lawsuit is replete with real-world examples of voters who lack the necessary IDs to vote.

Wisconsin election officials test out the voter ID law with “soft” enforcement during the recall elections of 2011, asking voters to show a photo ID but not requiring it. Other provisions of the law take effect immediately, such as the new 28-day residency requirement.

2012 – First Courts Block Voter ID

Wisconsin’s voter ID law is scheduled to be in effect for the entire 2012 election cycle, including the high-turnout presidential election. Instead, it gets held up in multiple courtrooms.

The voter ID law does make its debut on Feb. 21, 2012, although the overwhelming majority of Wisconsin residents don’t vote in that election. It’s a non-partisan contest for a handful of local judge races.

On Feb. 23, 2012, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) of Wisconsin joins other groups in filing another federal lawsuit against the voter ID law, calling it “a voter suppression law that burdens African-American and Latino voters most heavily.” Plaintiff Bettye Jones is an African-American who has been a regular voter since the 1950s and lived most of her adult life in Cleveland. The LULAC lawsuit states Jones lacks not only a state-issued photo ID but also a birth certificate or other document needed to get one. Jones dies in 2012, but her lawsuit continues. The LULAC case is combined with the Frank v. Walker case in U.S. District Court Judge Lynn Adelman’s courtroom.

On March 6, 2012, Dane County Circuit Court Judge David Flanagan blocks Wisconsin’s voter ID law as he awaits testimony in the NAACP’s lawsuit. It’s the first in a string of court orders that would effectively keep the law shelved until 2016. Flanagan issues a final order later that year.

Dane County Circuit Court Judge Richard Niess, presiding over the League of Women Voters lawsuit, becomes the second judge to block voter ID in state court. “A government that undermines the very foundation of its existence – the people’s inherent, pre-constitutional right to vote – imperils its legitimacy as a government by the people, for the people, and especially of the people,” Niess writes in his permanent injunction. “This is precisely what 2011 Wisconsin Act 23 does with its photo ID mandates.”

Republican Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen appeals both decisions, but neither appeal proceeds quickly. The voter ID law remains blocked for Gov. Walker’s historic recall election in June of 2012 and the high-turnout November 2012 presidential election between President Barack Obama and Republican Mitt Romney.

2013 – The Law Remains Shelved

There’s no quick resolution to the voter ID lawsuits in 2013, and by the end of 2013, some Republicans wonder whether the law needs changes to survive in court.

GOP authors of the law get some good news in May of 2013 when the Wisconsin Court of Appeals upholds voter ID, ruling against the League of Women Voters in one of the state lawsuits. But practically speaking, the ruling doesn’t matter much. Voter ID remains blocked by the NAACP lawsuit, which has yet to work its way through the state appeals process.

The Frank lawsuit, which is now joined with the LULAC case, proceeds even more slowly in federal court. It goes to trial in November, but there’s no firm timeline on when District Judge Adelman might rule.

Some had speculated that the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s conservative majority might grant requests for expedited appeals, much as they had in 2011 for one of the lawsuits challenging Gov. Walker’s collective bargaining law. But for most of 2013, the Wisconsin Supreme Court remains silent on voter ID.

By November 2013, the Wisconsin Assembly decides to take matters into its own hands, passing a bill that’s aimed at helping voter ID prevail in court. It would loosen restrictions on voting, letting residents cast ballots without photo IDs if they sign sworn statements saying they’re poor and can’t obtain a photo ID without paying a fee. Senate Republicans are unconvinced. They don’t even debate the bill, deciding instead to wait out the legal fight.

On November 20, 2013, the Wisconsin Supreme Court finally gets involved in the voter ID legal battle, but not in a dramatic way. It issues an order announcing it has taken jurisdiction over the League of Women Voters and NAACP cases.

2014 – A Year Of Chaotic Legal Twists

The Wisconsin Supreme Court holds oral arguments in the League of Women Voters and NAACP cases on Feb. 25, 2015, and Justice Patience Roggensack raises issues that leave some questioning whether she might rule against the voter ID law.

Roggensack, a member of the court’s conservative majority, says she’s concerned someone who doesn’t already have a photo ID would need a birth certificate to get one. And if they don’t have a birth certificate, they’d have to pay the state to get a copy.

“I’m troubled by having to pay the state to vote,” she tells an attorney for the Wisconsin Department of Justice during arguments. Her question hints at a central complaint raised by lawyers for the NAACP: that the voter ID law in its current form amounts to an unconstitutional poll tax.

Less than a month later, Walker sounds worried that the law will fail, urging the state Senate to pass the changes to voter ID that the Assembly passed in late 2013. Walker says DOJ lawyers told him that the legislature should revise voter ID so it has better chances of holding up in court.

On April 29, 2014, U.S. District Judge Lynn Adelman issues the first federal ruling blocking Wisconsin’s voter ID law. “It is absolutely clear that Act 23 will prevent more legitimate votes from being cast than fraudulent votes,” Adelman writes in his 71-page order. The U.S. Department of Justice weighs in later in the year, underscoring the national significance of Wisconsin’s Frank case.

On July 31, 2014, the Wisconsin Supreme Court upholds the state’s voter ID law, but with a catch: Justice Roggensack writes what’s known as a “saving construction” into her NAACP decision. It “requires the issuance of DOT photo identification cards for voting without requiring documents for which an elector must pay a fee to a government agency.” Justice Patrick Crooks dissents, writing that the majority opinion either “fails to guarantee constitutional protections against poll taxes” or infringes on the duties of the legislature. The Wisconsin Supreme Court also upholds the law in its League of Women Voters decision.

Roggensack’s ruling proves critical to voter ID’s survival in federal court, too. During oral arguments in the Frankcase on Sept. 14, 2014, Judge Diane Sykes references the decision, asserting that the Wisconsin Supreme Court already addressed the voter ID law’s potential poll tax. Lawyers for the ACLU sound concerned, and for good reason. The 7th Circuit acts swiftly, issuing an order just hours after oral arguments that reinstates Wisconsin’s voter ID law for the first time in more than two years. Joining Sykes are Judges John Tinder and Frank Easterbrook, who would author the final decision now known as “Frank I.”

Moments after the 7th Circuit issues its order, Republicans celebrate, and Wisconsin’s Government Accountability Board announces its plans to enforce voter ID in the upcoming election. What happens next is a chaotic exchange of rulings from judges on the 7th Circuit, and a last-minute appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

While federal appeals are heard by panels of three judges — in this case, Easterbrook, Sykes and Tinder — there are 10 judges on the entire 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. On rare occasions, the entire court will hear a case or issue a decision, which is known as an “en banc” appeal.

In the Frank case, the full 7th Circuit splits 5-5 on whether to reconsider the case en banc. It then reaches an identical 5-5 vote on whether to rehear the case. The tie votes mean voter ID is again upheld.

But the efforts carry symbolic significance. The dissenting opinion on whether to reconsider is written by Judge Richard Posner, the author of the 2007 appeals court decision upholding Indiana’s voter ID law. Posner writes that in the years since Indiana’s ruling, states with conservative governments –like Wisconsin–have passed much stricter voter ID laws, despite little to no evidence of fraud. “Some of the ‘evidence’ of voter-impersonation fraud is downright goofy, if not paranoid,” Posner writes. Posner wants Wisconsin’s law invalidated.

The U.S. Supreme Court has the final say in 2014, less than a month before Wisconsin is scheduled to hold its first major election with a photo ID requirement. It issues a brief order that again blocks the law. While the court offers no explanation for its ruling, legal observers say it was likely a matter of timing. The U.S. Supreme Court has typically warned against courts making major changes to election laws so close to an election.

The ruling means Wisconsin holds its 2014 gubernatorial election without voter ID.

2015 – The Law Is Restored, A New Lawsuit Is Filed

The next order from the U.S. Supreme Court on March 23, 2015 is short, but significant. It denies the ACLU’s appeal of the Frank case, which restores voter ID as the law of the land in Wisconsin.

While the voter ID law is restored, it doesn’t mean the ACLU’s Frank lawsuit is dead. On March 26, it files a new motion with Judge Adelman on much narrower grounds. Whereas the initial Frank complaint sought to overturn voter ID for all voters, this latest version seeks to change the law for voters “who lack photo identification and face legal or significant practical barriers to obtaining photo identification.” Judge Adelman denies the motion. In his decision, he references his 2014 ruling that overturned voter ID, but indicates that he believes his hands are tied in this case. “I continue to believe that my decision was correct,” Adelman writes, “but the Seventh Circuit disagreed and I am bound by its decision.” The ACLU appeals to the 7th Circuit for a second time.

While the state and federal court systems have already upheld Wisconsin’s voter ID law by this time, a group of plaintiffs led by the liberal One Wisconsin Institute file a new lawsuit in Western District Court that casts a wider net than anything that came before it. It claims Wisconsin’s voter ID law, and more than a dozen other election-related laws, place a disproportionate burden on certain populations that tend to vote for Democratic candidates, including young people and minorities.

“We saw there were lawsuits filed from other organizations related to voter ID, but those weren’t the only issues,” says One Wisconsin Institute director Scot Ross. “We felt that there were enormous implications to allowing those pieces of legislation to go unchecked in the courtroom.”

2016 – Voter ID Proceeds Even As Lawsuits Succeed

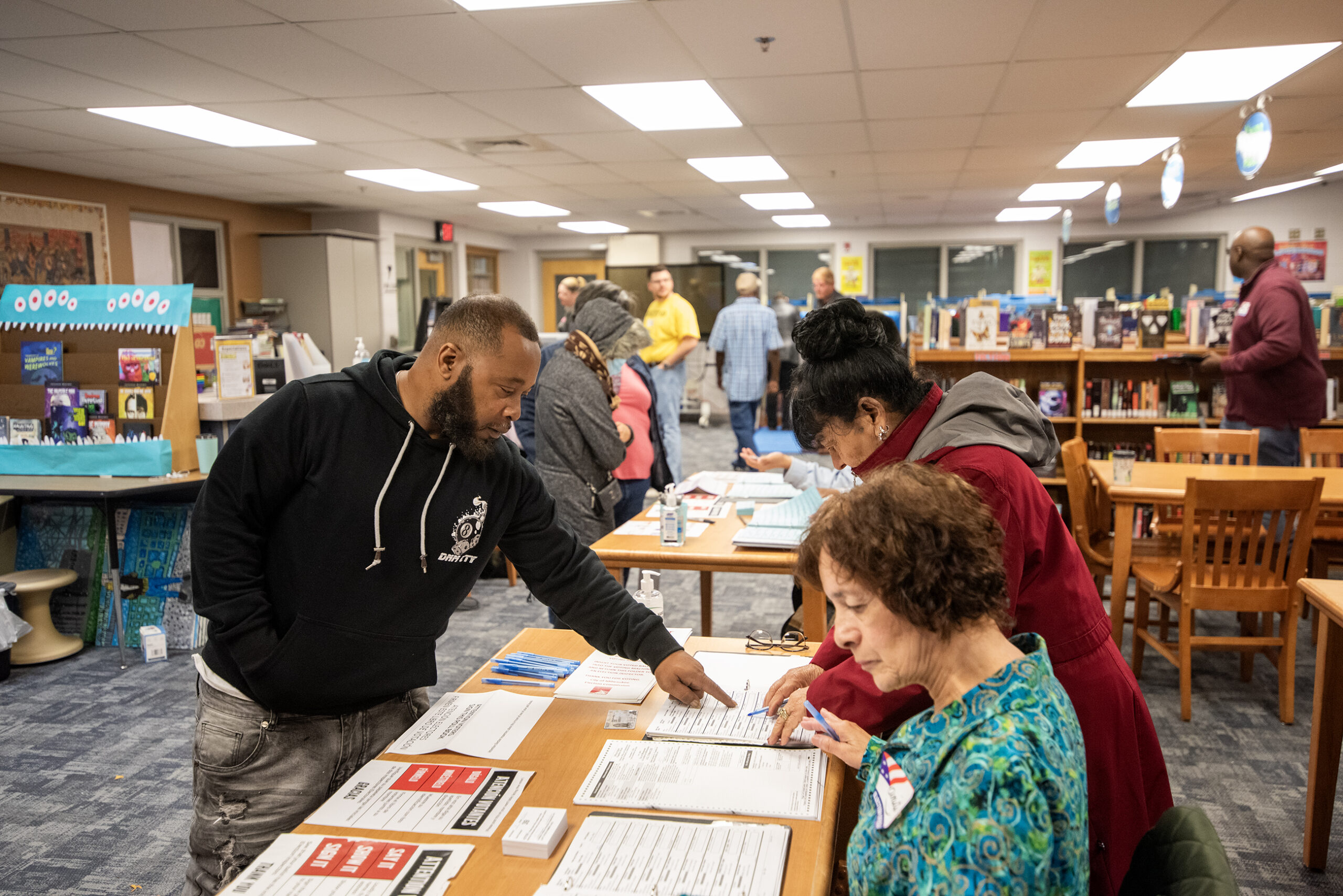

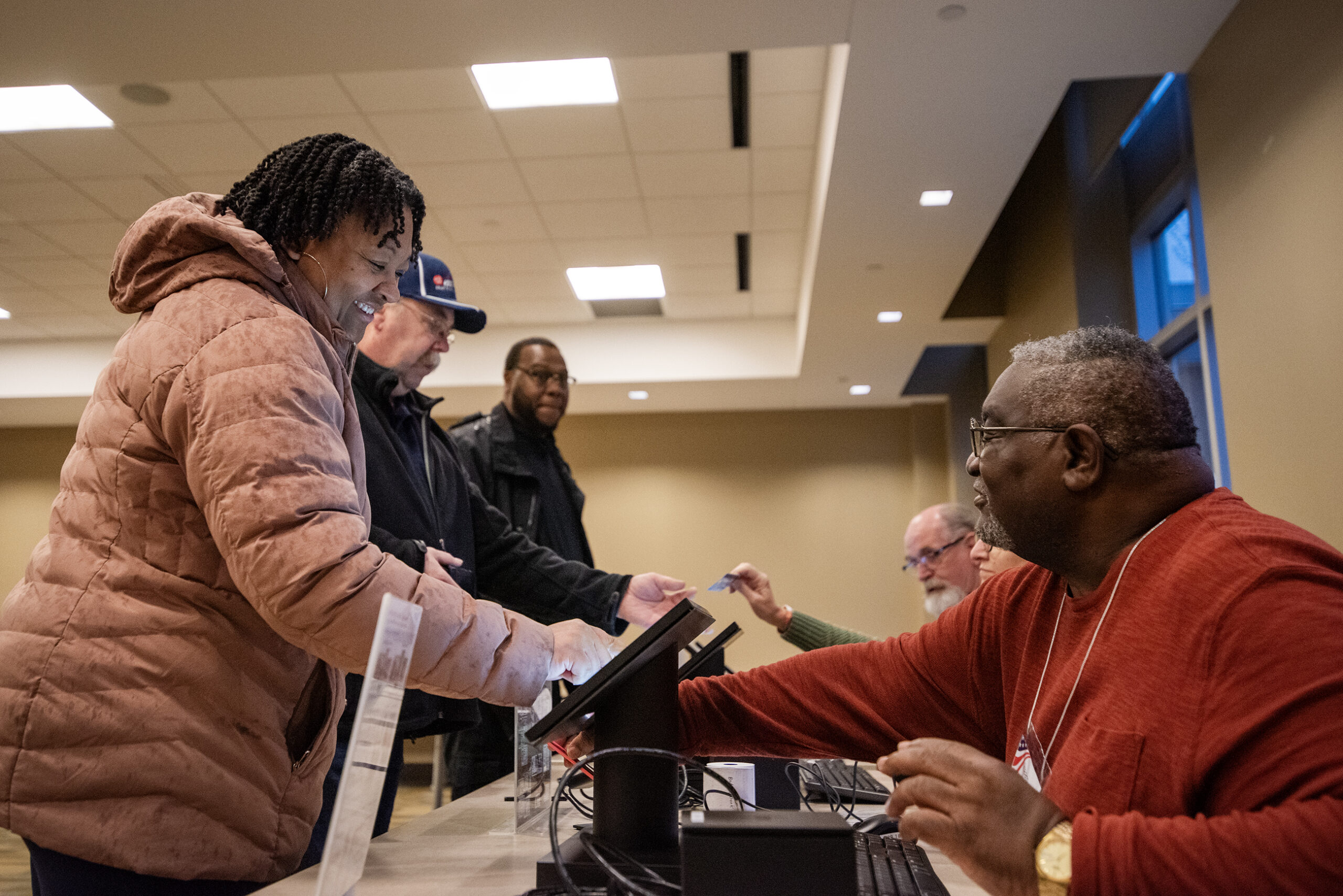

More than four years after it was passed, Wisconsin’s voter ID law returns for the February primary. While turnout is low — just 13 percent of eligible voters cast ballots–it marks the first election for statewide office with voter ID in place.

April’s election marks an even bigger test for the new law. Thanks to competitive Republican and Democratic presidential primaries–not to mention a State Supreme Court race — nearly 48 percent of eligible voters cast ballots. Republicans say the higher-than-usual turnout shows the voter ID law works and concerns that it would depress voter turnout were overblown. But there are reports in the April election of long lines throughout the state. “We know that voter ID is going to create longer lines because it takes longer,” says Government Accountability Board Director Kevin Kennedy. “A poll worker has to do more things when a voter comes in.”

Meanwhile, opponents of voter ID notch a victory in federal court as the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals issues a decision known as Frank II. It’s authored by Judge Easterbrook, who wrote the decision that upheld voter ID in 2014. This time, he strikes a different note. “The right to vote is personal,” writes Easterbook, “and is not defeated by the fact that 99% of other people can secure the necessary credentials easily. Plaintiffs now accept the propriety of requiring photo ID from persons who already have or can get it with reasonable effort, while endeavoring to protect the voting rights of those who encounter high hurdles.”

Soon after, the One Wisconsin Institute case goes to trial. U.S. Western District Court Judge James Peterson hears nine days of testimony as plaintiffs argue more than a dozen election-related laws have a disproportionate effect on populations that tend for vote for Democrats.

The Wisconsin Department of Justice argues Wisconsin’s election laws increase voter’s faith in the integrity of elections. At the trial’s conclusion, Judge Peterson says there’s a good chance his verdict will make both sides unhappy.

Before Peterson can rule, there’s another decision in the other ongoing federal lawsuit. Given the blessing of the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals to revisit the Frank case, Judge Lynn Adelman rules in favor of the ACLU plaintiffs. He orders the state to let people vote if they sign a sworn affidavit declaring that they’re unable to obtain a photo ID. “A safety net is needed for those voters who cannot obtain qualifying ID with reasonable effort,” Adelman writes in his July 19, 2016 order. “The plaintiffs’ proposed affidavit option is a sensible approach.”

Ten days later, Judge Peterson upholds Wisconsin’s voter ID law in the One Wisconsin Institute case, even as he calls the voter ID law “a cure worse than the disease.” But Peterson’s 119-page ruling is a win for plaintiffs as he strikes other Republican-authored election laws passed since 2011, including the 28-day residency requirement and limits on early voting. Peterson also orders changes to a petition process for people who can’t easily obtain a state-issued ID, though he later suspends his own ruling on that provision.

At this point, both the Frank and the One Wisconsin Institute cases are in the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals’ hands. It rules first on the Frank case, blocking Judge Adelman’s decision that would have let voters cast ballots without photo IDs if they sign sworn affidavits. That Aug. 10 decision, issued by Judges Easterbrook, Sykes and Michael Kanne, all but guarantees that an affidavit system won’t be in place for Wisconsin’s November 2016 election.

The same three judges rule on the other federal case just 12 days later, only this time they side with the One Wisconsin Institute plaintiffs and let Judge James Peterson’s ruling stand. The Wisconsin Department of Justice decides not to appeal the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, meaning early voting will be back in place for the November 2016 election.

Wisconsin communities are hesitant to make plans at first, but the Madison City Clerk is quick to announce it will allow early, in-person absentee voting starting Sept. 26, which is earlier than ever before. Milwaukee officials soon announce they’ll start offering early voting the same day. Both communities also expand in-person absentee voting to more polling locations.

Those same clerks are also preparing for Wisconsin’s first presidential election with voter ID.

November 2016 and Beyond: What’s Next?

After years of tumult and partisan back-and-forth over voter ID, the law is poised for its first real test in November.

Will it encourage voter confidence, as Republicans contend? Or will it disenfranchise voters, as opponents argue?

According to one expert, some insight can be gleaned from states that have already implemented voter ID laws.

Barry Burden, a professor of political science at the UW-Madison and an expert witness in Wisconsin’s two federal voter ID challenges, says there have been just two widely accepted studies of the effects of voter ID laws on elections.

“We’re just starting to get good evidence about that,” Burden said. “The laws have been in effect just long enough.”

One of those studies was released in 2014 by the non-partisan Government Accountability Office. The other was released earlier this year by a researcher at the University of California-San Diego.

The Government Accountability Office Study found voter ID laws lead to decreased voter turnout in general, and particularly decreased turnout for young people and African-Americans.

The UC-San Diego study had similar results, but said the law negatively affected more minority groups, including Hispanics and mixed-race Americans.

Data aside, Wisconsin politicians and activists have weighed in with their thoughts on how November’s election will be affected by the new photo ID requirement.

In a September press release, Republican Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald wrote the law is “hardly an onerous one” for voters.

“As Americans, we are regularly required to provide a photo ID for countless everyday tasks: driving a car, cashing a check, purchasing alcohol or tobacco, applying for government assistance, opening a bank account, applying for a job, picking up a prescription, or even purchasing cold medication — the list goes on,” Fitzgerald wrote. “Very few of these ordinary actions are as important for Americans as exercising our right to vote, and even one fraudulent ballot cast lessens the value of each citizen’s legitimate contribution.”

A spokesman for Walker said the governor is working to make sure all voters are prepared to vote in November.

“Governor Walker continues his work to ensure the people of Wisconsin are informed about where and how they can obtain a valid voter ID,” spokesman Jack Jablonski said via email.

At the other end of the spectrum, advocates who have battled against the law in court say it will confuse and alienate voters.

“We are still concerned about people getting an ID,” said Andrea Kaminski, executive director of the League of Women Voters.

Kaminski’s sentiments were echoed by One Wisconsin Institute director Scot Ross.

“There are going to be people who are disenfranchised as a result of the voter ID law,” said Ross. His group’s lawsuit is ongoing.

Kevin Kennedy, the former elections administrator, agreed.

“We will see people struggling,” Kennedy said. “Voter ID is going to work for the vast majority of people, but it’s not going to work for all qualified people.”

The prospect of voter confusion about the law was compelling enough to the state Legislature that it approved $250,000 for a statewide voter ID education campaign this summer. The campaign is running on airwaves, television screens and social media websites across the state in the lead-up to November.

“This summer, it seemed like there was legal news every week,” said Burden. “The fact that the legal decisions are bouncing around so frequently probably makes it confusing for voters.”

Residents with current state-issued drivers’ licenses won’t have much trouble voting. People who aren’t sure whether they have what they need to vote may want to read up on some of the law’s latest changes.

More changes aren’t likely between now and the November 8th election. People are already voting, and they’re showing photo IDs to cast their ballots.

But two of the lawsuits that shaped the law — Frank and the One Wisconsin Institute case — are still alive, and still evolving.

And as federal courts elsewhere strike down voter ID laws, such as North Carolina’s, lawyers targeting Wisconsin’s law say its days may be numbered.

“Frank I,in a lot of ways, seems to be out of step with the state of the law,” says attorney Karyn Rotker of the ACLU of Wisconsin. “The Appellate Court could decide to reverse that decision.”

The ACLU, or another critic of voter ID, may yet bring such a challenge in 2017 or beyond.

In Wisconsin, the fight over election laws never stops.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.