Although the Waukesha School District Board reversed course from June and opted into a temporary federal program that’s providing free meals to all students, several questioned the need for any federal school lunch programs in Waukesha schools — and promised they would revisit the issue.

The emergency meeting Monday night was set to address whether Waukesha should start the school year using the National School Lunch Program, the tiered free, reduced and subsidized lunch program schools have used since 1946, or whether it should join every other eligible school district in the state in using the Seamless Summer Option, a pandemic relief program that offers free lunches to all students through the end of the school year regardless of their ability to pay.

Universal Programs As A Safety Net

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Karen Tredwell, director of the Waukesha Food Pantry, said she was heartened by the board members’ highlighting of all the community’s resources for hungry families — from her own and other food pantries, to the Blessings in a Backpack nonprofit that sends children home with food for the weekends, to other federal programs.

However, she said, her organization supported Waukesha continuing with the universal free lunch program because it makes it more likely that children’s needs will be met, especially in a time of higher need.

“My contention is that very few of those resources can do it all,” she said. “We really do want to make sure that there are different options for the families that we serve, so that they don’t have to worry about not paying utilities, rent and so forth.”

She said that when students had to apply for free and reduced options, she found that families who were eligible for reduced-price meals still couldn’t always pay for students’ lunches.

“It’s still hard to come up with the funds to pay for those reduced meals,” she said.

Andrew Ruis, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of a book about the origins of school lunch, said universal lunches are good for families as well as children even beyond providing meals to students who need them.

“One of the things that school meal programs have always done, going back to the turn of the century, is that they’re extremely beneficial for parents and in particular for mothers, who tend to bear a larger portion of the child care burden,” he said.

Food Service Without Federal Assistance — Or Regulation

Although a narrow majority voted to go with the Seamless Summer Option, several board members questioned whether Waukesha should participate in any federal lunch program at all.

Board members and officials said the School District of Waukesha has a $1.75 million budget surplus, but because of the restrictions on how federal funding can be used, the district is limited in how it can spend down that surplus. Board members also said they didn’t appreciate the way the federal plan set prices and factored in price increases that they said weren’t necessary.

Michael Gasper, director of the Holmen School District’s nutrition program and former president of the Wisconsin School Nutrition Association, said under the federal Free and Reduced Lunch program, if a school district finishes the year with a positive fund balance, they can sign a waiver so they don’t have to raise their prices to students.

“We’ve enacted that in Holmen, I think, for the last four years, because we’ve had a positive fund balance,” he said. “We haven’t raised prices.”

Given Waukesha’s large budget surplus in school nutrition, several members suggested the school district set up its own food service program independent of federal money and federal regulations.

Ruis said it’s an option wealthier districts have tried elsewhere. However, he noted, most did so because they had such low participation in the National School Lunch free and reduced program that the tradeoff of extra paperwork for limited federal funds didn’t make sense.

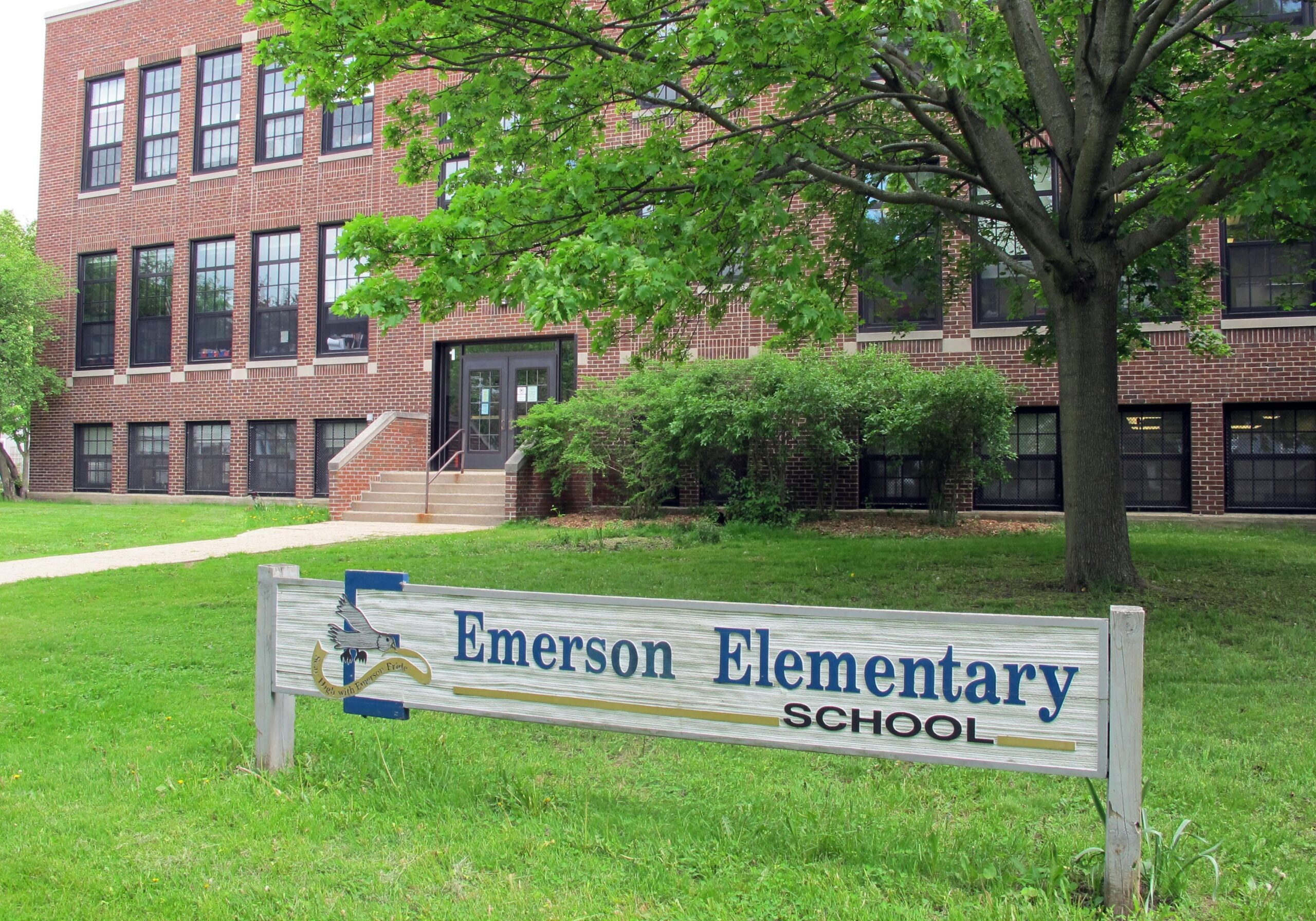

In Waukesha, by contrast, nearly one-third of students were eligible for free or reduced lunch in the 2018-19 school year and several schools had such a high proportion of eligible students that they already had universally free lunches before the pandemic under the 2012 Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act.

Ruis said the districts that eschewed federal funds and regulations in favor of setting up their own lunch program — and subsidizing low-income students themselves — served less-healthy meals.

“In these wealthier districts that had opted out of the national school lunch programs, the nutritional quality of the lunches was worse because they didn’t have to meet the nutritional standards of the USDA,” he said.

Gasper, in Holmen, said the nutrition guidelines are a key piece of the federal program.

“The amount of sodium per meal, the amount of fat per meal, the amount of calories per meal, the whole grains,” he said. “If you leave the federal program, you wouldn’t have to certify your menus that they meet the nutritional requirements, so the potential is there for a meal that’s not as healthy anymore.”

Tredwell, of the Waukesha Food Pantry, said one high school in the county that set up its own meal program saw costs increase.

“The idea of that is appealing in some ways because a district could have greater autonomy,” she said. “But the reality is that the meals are going to be much, much more expensive.”

School Nutrition Programs As Data Collectors

One of the perks of the Seamless Summer Option for nutrition programs has been that they don’t require families to fill out forms to apply for free or reduced-price meals, which Gasper said makes it easier for nutrition directors to focus on the food.

“It doesn’t make sense for us to be spending all our time on paperwork,” he said. “Every school nutrition director needs to be in the kitchen, because that’s where the rubber hits the road.”

However, without that form, which asks about a family’s income, board members worried they would have a harder time identifying students from low-income families who need other kinds of support. The data on how many families meet certain low-income thresholds also determines how much federal Title I funding a district receives to support financially needy students.

Tredwell said her organization has offered to work with the school board to help collect that income data.

“The pantry will do what we can to assist the families in filling out those forms, and coming up with some additional strategies that may help the school district in getting the information that they need,” she said.

Gasper said there have been far fewer applications for free and reduced lunch filled out as a result of the universal free meal program, but that he’s not convinced those income forms should have been in the domain of food service in the first place.

“I don’t understand why a school nutrition program needs to be the gatekeeper for all that information,” he said. “You can’t tell me that there isn’t another way to get that information.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.