Wisconsin hospital leaders are sounding the alarm as the state endures another COVID-19 surge. The seven-day average of new infections is over 3,500 — the highest it’s been in a year.

During a roundtable discussion hosted by Wisconsin Health News on Tuesday, hospital leaders said they have reached a crisis point.

“We are full. Period,” said Eric Conley, CEO of Milwaukee’s Froedtert Hospital. “It’s really impacting, impeding care for those patients who are not COVID that need the care getting in because getting to our beds is just very, very hard.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

According to the Wisconsin Hospital Association COVID-19 dashboard, there were 1,630 people in the state hospitalized for COVID-19 as of Tuesday afternoon — an increase of 212 over the past week. More than 400 of those patients are in intensive care units, which are in short supply.

“Unfortunately, it’s not looking good and I don’t think it’s looking good for anybody across the state or even across state lines. Our ICUs are pretty much full,” said Dr. Imran Andrabi, CEO of ThedaCare.

As of Tuesday, hospitals in the Fox Valley and north-central Wisconsin regions reported having only one or two intensive care unit beds available. Hospitals in the northwestern and western part of the state reported having zero ICU beds available. And in southeastern Wisconsin, the number of available beds was cut in half overnight — from 30 on Monday to 15 on Tuesday.

“The hardest part of this is that the delta surge is accelerating while we’re still thinking about what other variants might exist and how they’re going to impact our organization,” said Sue Turney, CEO of Marshfield Clinic Health System.

At Froedtert, Conley said COVID-19 patients make up about 13 percent of occupied beds, but that number is as high as 40 percent in some hospitals.

Every leader at Tuesday’s panel said the vast majority of new COVID-19 patients are unvaccinated — from 74 percent at Marshfield Clinic to 88 percent at Froedtert.

And this surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations is sending shock waves through the hospital systems.

“Not only does it affect patients with COVID, it also affects all the other patients that we have to take care of, with strokes and heart disease and cancer diagnoses and diabetes and all of those kinds of things,” said Andrabi.

With limited beds and staff capacity, hospital leaders said they have had to turn some patients away even when they needed emergency care.

“We are in a crunch in really taking care of other patients that really need medical care,” said Turney. “And we now are again delaying (elective) procedures, delaying screening and other types of routine care because we just don’t have enough capacity.”

And the situation is the same at nearly every hospital in the state.

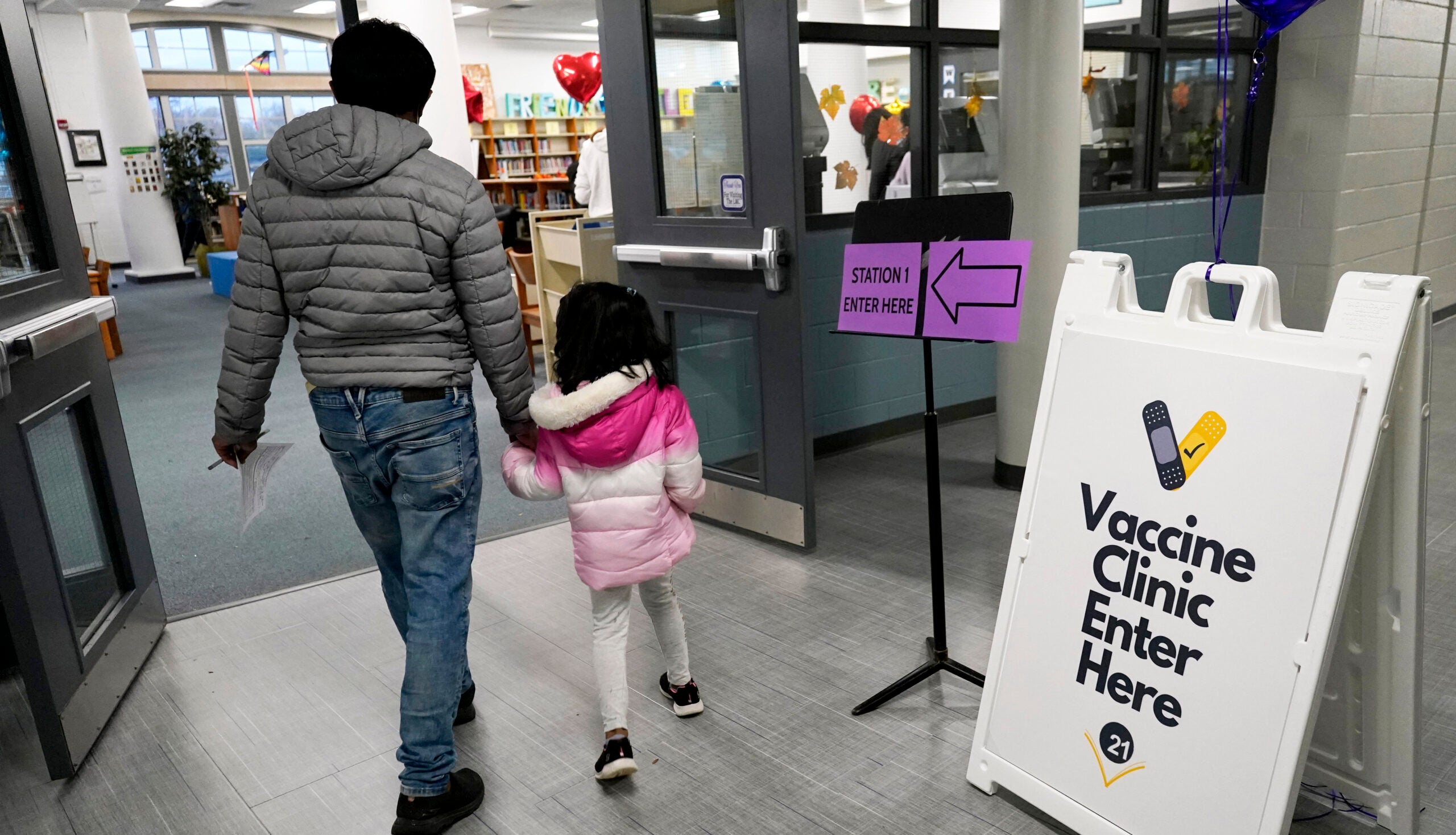

“You can’t call out to anybody else to help because they’re all in the same situation. So the only way to sort of help this situation is we get vaccinated so we have fewer people coming into the hospital and emergency rooms,” said Andrabi. “Whether it’s omicron, or it’s delta, or it’s anything else, we know that the COVID vaccine is a good way to go.”

In fact, every panelist at Tuesday’s discussion urged vaccination.

“I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t advocate for the COVID-19 vaccine and its booster as they have proven to be the safest and most effective way to prevent and lessen the severity of COVID-19,” said Conley.

What makes the situation worse is that health care — like most industries — is experiencing a staffing shortage. But panelists said this is especially acute in hospitals where health care workers are burned out after a grueling 21 months.

According to Andrabi, 15 to 18 percent of health care workers have left the industry since the pandemic.

“You know, call it the Great Resignation. I call it the pandemic of the pandemic,” said Bernie Sherry from Ascension Wisconsin.

But the demand for health care workers has only risen, and Sherry said hospitals have increasingly been forced to rely on short-term fixes like traveling nurses who are often from out of state.

“That’s not really where we want to be in delivering health care, is third-party agencies,” said Sherry. “Over time, we have to address that from a health care systems standpoint.”

Every panelist agreed that this latest crisis points not only to the crucial role of vaccines, but to a need for broader, long term changes within the health care system that extend beyond COVID-19.

“These challenges are not going away,” said Andrabi. “We are not going to be able to hire out of this situation. So let’s just put that truth out there, at least from our perspective, and then say, ‘Okay, then what has to be true?’”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.