Brent Sinkula has been operating the Irish Acres dairy farm for 12 years. Before that, it was his father’s farm, and his home.

“Since I was 5 years old, I was out there feeding calves and helping out,” Sinkula said.

As president of the Manitowoc County Farm Bureau, Sinkula understands the challenges Wisconsin dairies are facing. The changing dairy market has made it more difficult for small and mid-sized farms to continue.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Small dairy farms with fewer than 200 cows can survive, Sinkula said, because a single family can run them without the expense of hiring outside labor. And large farms, those with more than 1,000 cows, can afford to hire help because their size means more profit.

At around 400 milking cows, Irish Acres falls somewhere in between.

“That middle seems to be kind of falling out,” Sinkula said, “and that’s kind of where I am.”

Without plans to expand the dairy, Sinkula was looking for another way to maintain the family farm. In 2018, an energy company approached him interested in renting 500 acres, about a third of his land, to install solar energy panels.

For Sinkula, hosting solar panels on his land provides a financial safety net for the farm. He’s not the only farmer to make similar arrangements. Farmers have what solar energy companies need: land. Across the state, partnerships between dairy farms and energy companies are increasing, changing the landscape and providing farmers extra revenue in a sometimes unpredictable market.

That unpredictability can take the form of a yearslong dip in milk prices, or unfortunate weather. Wisconsin had record-setting rainfall in 2018 and 2019, increasing the challenges farmers faced.

“We were just fighting to get the crops off, getting stuck, breaking axles on wagons, I mean, all kinds of problems,” Sinkula said. “And then you get off a crop that’s lower quality that you have to spend more money to dry.”

That’s when lawyers for NextEra Energy offered Sinkula and his father, who owns adjoining property, a 30-year lease for use of their land.

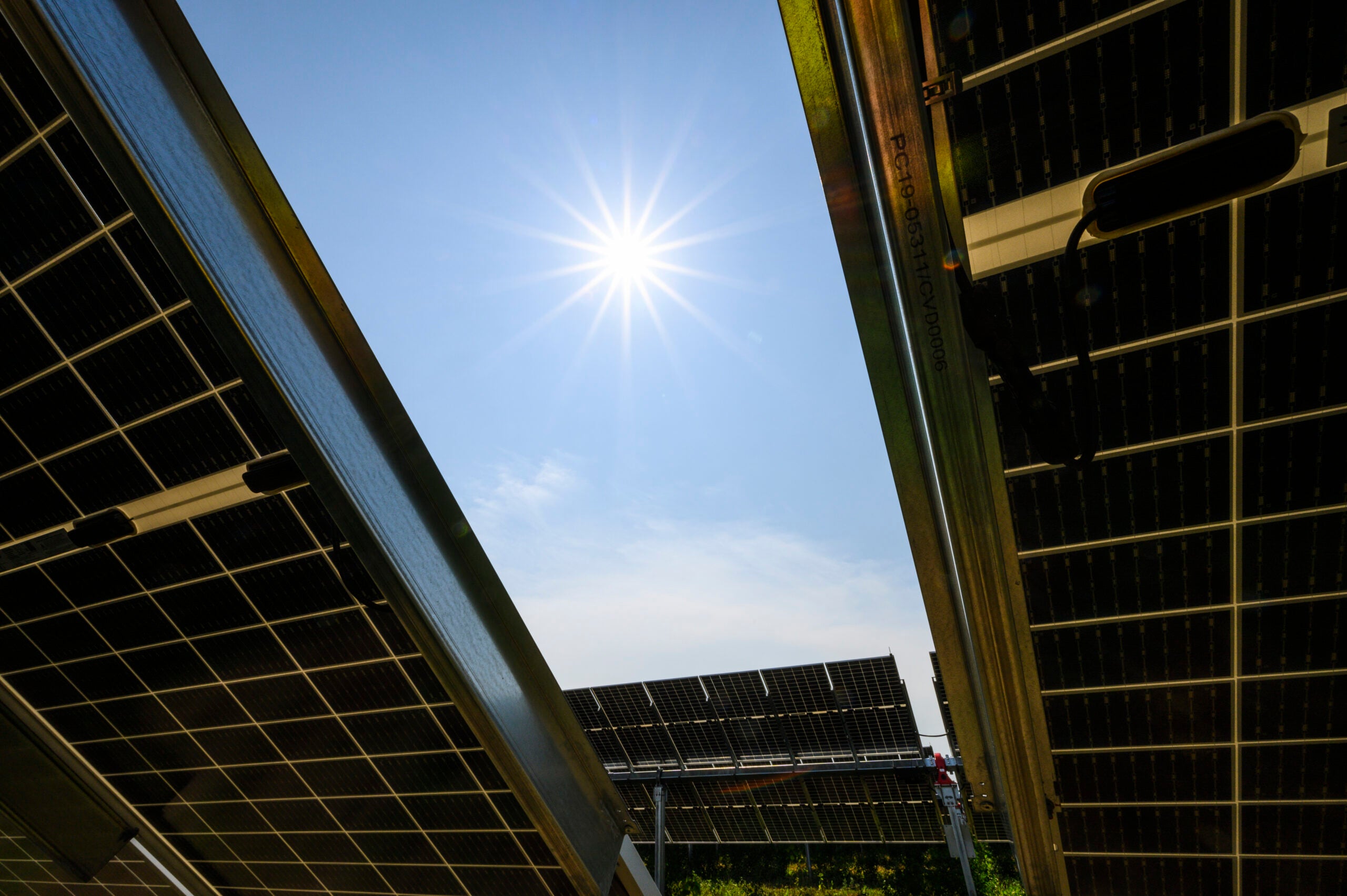

Four years later, the cows on Irish Acres dairy graze right next to rows and rows of glistening photovoltaic panels absorbing the sun’s rays.

Solar farm growth along Wisconsin’s lakeshore part of a national move toward renewable energy

Sinkula’s farm is located in the small, lakeshore town of Two Creeks, nestled between Manitowoc and Door County.

After the Sinkulas began working with the solar developers, at least four other landowners followed. NextEra Energy has developed two large-scale solar farms in Two Creeks.

The growth of renewable energy is not just a statewide trend; it’s nationwide. The U.S. recently reached 20 percent renewable energy generation, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. And in Wisconsin, due to advanced technology and declining costs, most of that growth is happening in solar.

“A lot of the companies in the United States that practice in the renewables area have shifted a lot of their efforts to large-scale solar design,” said James Tinjum, who researches environmental sustainability and renewable energy at the University of Madison-Wisconsin. “The economics has, in the last decade, made it possible.”

According to Wisconsin Public Service, which along with Madison Gas and Electric now owns the lakeshore solar farm, the Two Creeks Solar Park contains approximately 500,000 solar panels spread across 800 acres capable of producing 150 megawatts of energy, enough to power 45,000 homes.

A second project came online from Two Creeks last year. The Point Beach Solar Energy Center spans over 450 acres and has the ability to produce 100 megawatts of energy, the amount approximately 25,000 homes require.

Despite new projects in Two Creeks and elsewhere, Wisconsin significantly trails neighboring northern states like Michigan and Minnesota in renewable energy development.

Tinjum said it’s partly because Wisconsin’s farms tend to be divided into smaller plots of land. In states like Iowa and Minnesota, vast, thousand-acre farms growing corn or grains are more common than Wisconsin’s smaller dairy farms, which can make large-scale leasing easier.

Energy infrastructure can help communities pay the bills

Lee Engelbrecht has been Two Creeks town chairman for over a decade. He’s been a public servant for his tiny hometown for over 40 years.

“Two Creeks is only half the size of a regular town,” Engelbrecht said. “The other half, I always say, is out in Lake Michigan.”

Since the 1970s, Two Creeks has also been home to the Point Beach Nuclear Plant. Large-scale transmission lines cut across the northeast Wisconsin communities. Many of them were installed decades ago to connect to the power plants along the Great Lake.

The town and the county receive utility tax payments for hosting energy facilities. The influx of revenue from the nuclear power plant in the 1970s allowed the town to fund a fire department, give residents a property tax break and provide them cable television.

Tinjum said there are three things that make a community ideal to develop energy facilities: transmission capacity, willing landowners and a power purchase agreement.

“You got those three things, you’ve got a project,” Tinjum said.

Existing infrastructure like transmission lines to move the energy is a big reason why energy companies are attracted to Two Creeks, he said.

The town receives around $230,000 annually in tax benefits for the nuclear plant. Now, due to the two large-scale solar farms, it will bring in about $400,000 more.

Engelbrecht hopes the additional money can be used to help maintain the town roads.

“I think it’s good for the town. It’s good for the county,” Engelbrecht said. “We need energy. Everybody wants to go to that light switch and expect it to go on when they flip it on.”

New energy facilities sometimes receive pushback from residents

Not everyone is happy the solar farm has been built in Two Creeks. Sinkula has gotten some negative responses from neighbors.

At a local farm bureau meeting, he was asked by another farmer if he could put a price on the cost of the negative feelings the solar projects spurred.

“I told him point blank, there’s no dollar value you can put on that. I said, just prepare for some backlash,” Sinkula said.

Sinkula said at state Farm Bureau conventions, members put forward proposals both in support of and against farmers collaborating with solar developers. Opponents think it creates competition for farmland and can raise prices.

Around 2000, an energy company approached farmers in Two Creeks about hosting wind turbines on their land for a wind farm.

Ken Duveneck was then town chairman. He said many folks were opposed to the idea and called it a divisive time. The wind project never materialized.

Current chairman Engelbrecht remembers folks having concerns about the impact on groundwater, sound barriers from the blades and stray voltage. He said it was a different story for the solar development.

“We didn’t hear any pushback on the solar panels like we did with the wind turbines,” Engelbrecht said.

Locating a solar farm in northeast Wisconsin is a bit of an experiment. According to NextEra, the Two Creeks solar projects are some of the most northern developments the global company constructed.

Tinjum thinks that in a climate like Wisconsin’s, renewable energy technologies have the opportunity to complement each other. Solar panels produce less in winter, when wind energy is strongest. Wind production declines in August, when solar energy is peaking.

NextEra doesn’t plan on slowing down its solar energy development, in Wisconsin or elsewhere.

“We’re very excited about the opportunity for renewable energy to continue to grow in this country,” said Jeff Bryce, a senior project manager with NextEra Energy Resources. “We’ve got a lot of current investment in the state of Wisconsin, nearing $2.2 billion.”

For farmers in Two Creeks, working around energy infrastructure has always been part of the landscape. In 1966, the Wisconsin Electric Power Company announced plans to construct the Point Beach Nuclear Power Plant. Tucked in the woods adjacent to Point Beach State Park, the plant began producing energy along the lakeshore in 1970.

Another nuclear power facility came online four years later, just five miles away across the county line in Kewaunee.

Today, about 17 percent of Wisconsin’s electricity comes from nuclear power, said Mike Corradini, an emeritus professor in the Nuclear Engineering Physics program at UW-Madison.

Corradini said power generation facilities, like nuclear plants, need access to large bodies of water for cooling purposes, which make lakeshore communities an ideal location.

“You had something like six or seven or eight power plants, all nuclear plants, on Lake Michigan,” Corradini said.

Despite being awarded permits to continue operating for another 20 years, the Kewaunee nuclear plant closed in 2013 after failing to negotiate a power purchase agreement with utility companies.

The substation at the shuttered Kewaunee power plant is now being used to get the solar energy generated from the new Two Creeks solar farms on the grid.

Duveneck is also a former dairy farmer who signed a solar lease. Both he and Sinkula said they’ve been contacted by other farmers who’ve been approached by solar developers, who want to hear how it went for the Two Creeks farmers.

Duveneck predicts hosting solar panels will become more common for Wisconsin farmers. He’s seen how small dairy farmers now need to generate extra sources of income, whether that be raising beef, or selling strawberries or cheese.

And Engelbrecht said he would have seriously considered renting his land to a solar farm if he had the opportunity before he retired in 2003.

“I see dairying as a very vital part of Wisconsin’s economy,” Engelbrecht said. “It’s one way to hang on to some of these farms that maybe otherwise wouldn’t stay in business.”

Solar contracts provide retiring dairy farmers security

On the eve of his 75th birthday, Ken Duveneck recalls how by 2007 his health no longer made it possible to continue dairy farming.

“I had one knee replaced … and it was just getting to the point I couldn’t hardly do it,” Duveneck said.

Duveneck tried other ways to earn farm income.

“I kept raising heifers after that. I bought them and sold them,” Duveneck said. “That went good for a while, but then that market went out.”

A few years later, he switched gears again, growing corn and soybeans.

The Duveneck farm is located right along State Highway 42, less than a mile from the Sinkula family’s Irish Acres. Past the red barns and gravel driveway, 40 acres of solar panels now rotate towards the sun.

Like his neighbors, Duveneck and his wife Rita signed a 30-year contract to lease their land for solar energy generation.

Duveneck has lived in Two Creeks the same length of time he’s been farming — his entire life. He said the solar contract is an opportunity to keep the land, and farm, in his family. Without a buyer, many dairy farmers have to sell their land, cows and equipment off in pieces to retire.

Ken and Rita Duveneck can pass the solar contract down to their children.

Rita Duveneck said it was a hard decision to temporarily give up the farmland on their fourth-generation farm. However, she’s glad the solar infrastructure enables them to contribute to Wisconsin.

“We farm the sun,” she said.

Across the highway, Two Creeks farmer Laddie Frank found himself in the same position.

“I’m getting too old to farm anymore,” Frank said. “I’m up in my 80s already, so it doesn’t go as easy as it used to.”

Solar panels were also installed on 40 acres of Frank’s land about a year ago. They’re nestled next to the small woods on his property.

The money from the solar contract provides a secure income for Laddie Frank and his wife Lynne in their retirement.

Along with the solar panels, the Franks have a 30-year-strong orchard of apple, cherry and pear trees.

“That’s more than enough for me,” Frank said.

Jana Rose Schleis is a Smith Patterson Reporting Fellow from the University of Missouri School of Journalism. Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.