It’s no secret that friendships are more difficult to maintain as we age. Whether it’s careers, kids, family — you name it — good intentions and plans to actually see and connect with friends on a regular basis often fall short.

But neglecting friendships can have dire consequences. Loneliness in the United States — particularly among men — is a widespread problem. More than one-third of Americans over the age of 45 suffer from chronic loneliness, and in 2017, the then-Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared it a public health epidemic.

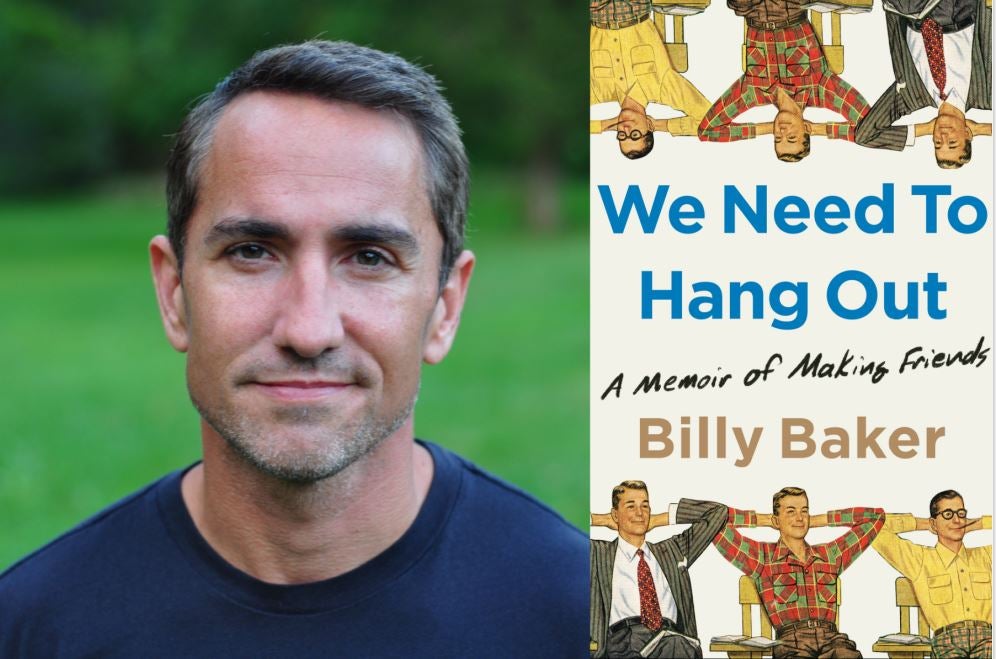

Despite how widespread it is, talking about loneliness can clear a room, said journalist Billy Baker. And that’s part of the problem. Data shows loneliness can have dramatic impacts on health, mentally and physically — ailments like heart disease, diabetes and early death are sharply increased by loneliness.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Baker never thought of himself as lonely until an editor assigned him a story about loneliness among middle-aged men. At first he resisted the assignment, rationalizing that as a middle-aged dad with a wife and kids it was normal not to see friends.

“My first thought was … I have plenty of friends,” he said. “But it really took just a short walk back to my desk to realize … these people I think of as my best friends, it was like I haven’t seen that person for a couple of months, I haven’t seen that guy in years.”

Baker’s article was so popular, he’s now written a book about his experience reviving old friendships and making new ones. He recently spoke with WPR host Kealey Bultena about his book, “We Need to Hang Out.”

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kealey Bultena: One thing that resonated with me was the waves of outreach you describe. You wrote the article, people reached out to you, you wrote a follow up, and experienced another wave. Something happens in our lives that generates conversation, and then it creeps back to silence again. Tell me more about that.

Billy Baker: In the original article, I kind of raised my hand and admitted to being a little bit of a loser, I didn’t have any space in my daily life for friendship. And then everyone I knew bent over backwards to reach out.

What was interesting was by raising my hand, I kind of created a safe space for others to raise their hands. The reaction was never wanting proof that there really was this cancer, it was more like, what’s the cure? And in a weird way, it’s like the easiest cancer in the world, right? Like the cure for loneliness is friendship.

At first my reaction was to try and reconnect with friends from the past and I had some success. But if I really wanted to have the benefits that come with friendship, what I needed to do was build friendship into my daily life and do one of the most awkward things, which is to make new friends.

I was guilty of thinking this would just happen naturally, but everyone was kind of, it seemed, locked into the same cycle of commitments. Ultimately, I tried to find ways to connect over an activity. Things like weekly book club or weekly adult sports league or a Fantasy Football league. Whatever it was, I needed to define those with each of the people that I really wanted to connect with.

KB: To make new friends you had to go through some things that felt really embarrassing to you, talk about that.

BB: I got to this point where I was like, I’ve done a lot of work, but I still don’t have anyone to hang out with on a Wednesday night. So I tried to start this club that meets in a bar. And it was the simplest thing in the world. I invited a bunch of guys and I went there a little early, and it was like I was back in sixth grade again, like afraid to walk into the school dance, the nerves. Vulnerability is the only word for it.

It’s like when you reach out to an old buddy and say, ‘Miss you, we should hang out.’ They’re thinking the same thing, it’s just for some reason we’ve been trained to think that that’s just not a thing to do. It was a barrier in a lot of my friendships and thankfully, those barriers are falling.

KB: You’ve done so much reaching out, put so much intention into inviting people to do things. Honestly, it sounds exhausting. Is it worth it?

BB: 100 percent. The person I am at the end of this journey as opposed to where I began … I feel like I’m faking it a little bit as I’m talking about like, this lonely person that I was, because I don’t feel that way anymore.

There were so many things that were so illuminating. When science studies the way people interact, there is a clear difference in the ways that men interact versus the way women interact. Women talk face to face and men talk shoulder to shoulder. And when we think about that idea of shoulder to shoulder, it goes back to this idea that men tend to bond over an activity.

Before all this, when I’d see an old friend we’d say we should get together to get some coffee or something like that, it didn’t sound all that appealing. But if the same person had said, ‘Hey, do you want to come over and help me chop down this tree in my backyard?’ I would have been there at 6 a.m. I used science to hack my friendships, and it worked.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.