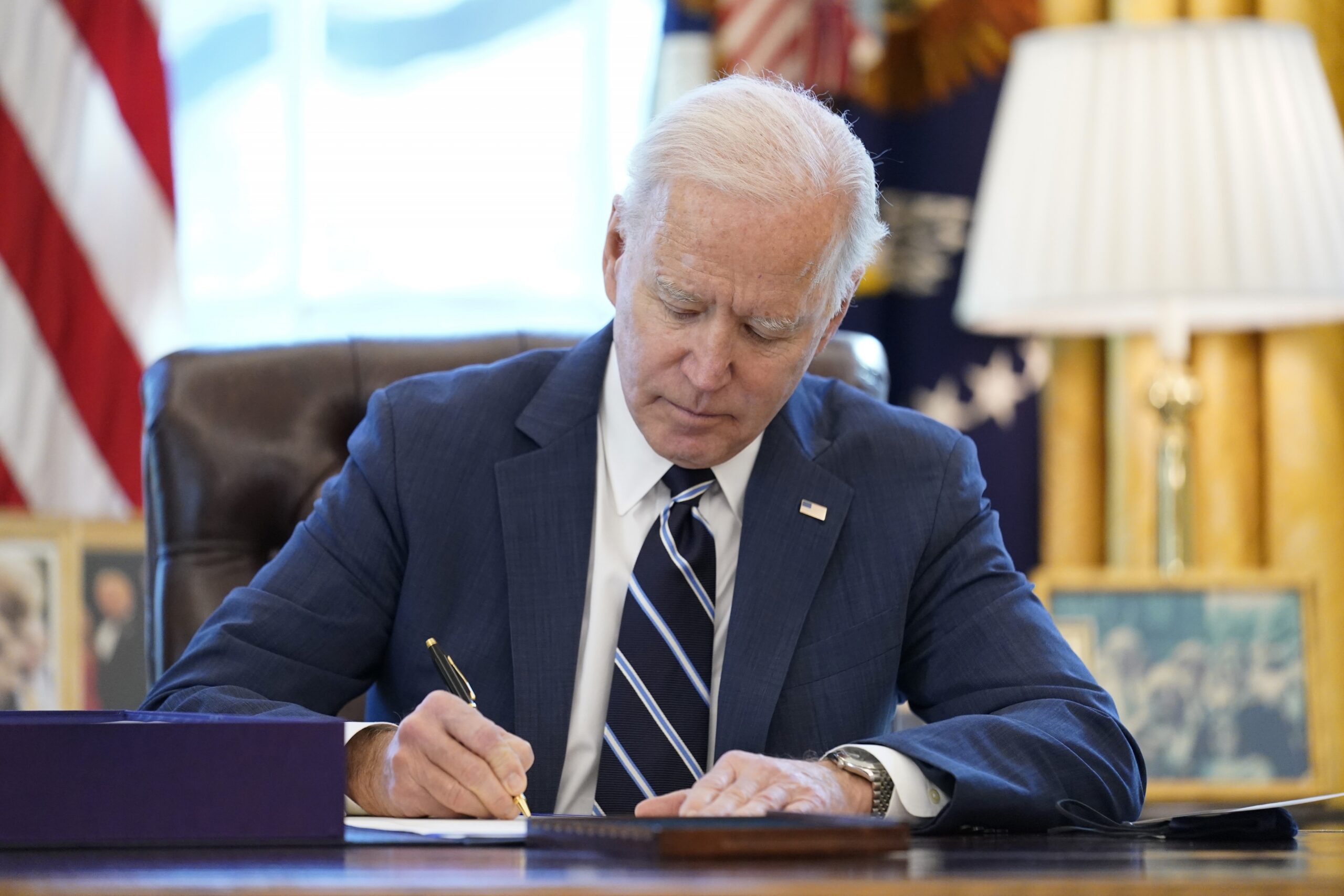

Last week, President Joe Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act, the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package.

Included in the recovery bill is an increase in the child tax credit, where many families could receive $3,600 for children under 6 years old and $3,000 for children between the ages of 6 and 17. Researchers say the legislation could reduce poverty by a third, bringing 13 million Americans out of poverty.

Dr. Sarah Halpern-Meekin, a professor of human development and family studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who specializes in social and welfare policy and families living in poverty, recently spoke with WPR’s “Central Time” host Rob Ferrett about the legislation.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rob Ferrett: What does this child tax credit do in comparison to the existing tax credits?

Sarah Halpern-Meekin: In the child tax credit that’s currently in existence, families were eligible to get up to $2,000 as a tax credit, and it was partially refundable. So if you didn’t owe any money and they owed you money, they’d send you a check.

There are some key changes from that old policy to this new policy.

So first, it expands the availability of that policy to families that were excluded or limited from that maximum benefit before. So if your earnings were not above a certain level before, you weren’t eligible for any or part of that $2,000 credit. So there are more families that are going to be eligible. Previously, families of about a third of American children were excluded from getting at least that full benefit.

In addition, the payments are larger than the existing tax credits, and there is one other key difference, which is that this legislation has directed the Treasury to figure out a way to make these payments periodic, so that families will get checks monthly from July through December, as opposed to just getting that one big check at tax time.

RF: President Biden addressed the nation after signing it into law, and he talked about the anti-poverty impacts of a lot of the different measures, not just the child tax credit. What do you see as the impact when it comes to poverty of not just the child tax credit, but the overall recovery act?

SHM: The poverty line for, let’s say, a family of three is just below $22,000 a year. And so when we’re looking to see, do these policy changes lift people out of poverty, we’re asking, will this difference in income lift them above that threshold?

And the simulations that I’ve seen show that we would expect that the policy changes that we have here to cut child poverty by 40 to 50 percent by raising the incomes of families who are below that poverty line so they end up above that poverty line.

But I think there’s also one other important thing to pay attention to. There are going to be families who aren’t lifted above the poverty line who might be lifted out of extreme poverty or deep poverty, so they might still be in a difficult financial position, but they’re going to be doing a lot better than they would have been in the absence of this money.

RF: The tax credit is this year only because of the nature of the bill, does the fact that at present this is a nonrecurring thing, does that make a difference?

SHM: Absolutely. I would expect that the changes to child poverty will likely be similarly temporary if the policy isn’t extended.

We’ve seen families experience an increase in their income over the past year in response to different congressional acts. Previous stimulus checks, previous increases in unemployment insurance have lifted families up during this tough economic time. But when those go away, the help that they offer the families goes away, too. And so unless we see a continuation of it through new legislation, I would expect that we would see child poverty rates rise once again.

RF: One criticism of this kind of measure is, OK, if people are getting these kinds of credits now, is it a disincentive for them to seek out jobs even as the economy recovers and hopefully jobs continue to come back?

SHM: So when I look at the research, it doesn’t show that payments of that size are likely to lead a lot of parents to leave the workforce. The money’s not nearly enough to live comfortably in our society. And we also want to keep in mind that people work for reasons other than financially having to, as we see many dual-income, high earner parents that could get by on one income and choose not to.

But I think this question we also want to think really hard about is whether we want to frame it as, is it always bad if parents work less? We should think about whether we want to consider parents spending more time with their children, by maybe cutting back on working hours as not necessarily bad. We tend to, in our society, view less employment as inherently bad. But that’s because we define all the time that parents spend taking care of their own kids as not being work. And as any parent knows, it certainly is work, and it’s a whole different kind of work.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.