Last Friday marked the first Wisconsin Badgers home football game of the 2020 season. It was one for the history books, and not because of what happened on the field: It was the first game the team played during the coronavirus pandemic, with the stadium virtually empty, and pastimes like tailgating heavily restricted. And just days later, the team had to hit pause on its season because a growing number of team members and staff have tested positive for COVID-19.

The historic season is just the latest chapter for Camp Randall, a site that already has a storied past.

One WPR listener wanted to learn more about the story of Camp Randall — not just the sports stadium, but the Civil War army camp that preceded it. They wanted to learn more about where the name Camp Randall came from, and whether there was any Native American history associated with the grounds.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

John Hanson of Madison submitted a question to WPR’s WHYsconsin: “I would like to know more about early Camp Randall history at the UW: as a Civil War troops training ground, the person it was named after — Gov. Randall — and any other interesting history events, up to its modern version. Thanks. Go Bucky!”

To answer Hanson’s question, WPR’s “Central Time” reached out to Daniel Einstein, the historic and cultural resources manager for the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Einstein is in charge of campus structures and landscapes; archeology, including effigy mound sites; public art, like university commemorative objects and statues; and the campus art collection.

Einstein pointed out that “all cultural landscape stories really begin with the Indigenous people who occupied this area since 12,000 years ago, after the retreat of the last glacier.” European settlers migrated to the Madison area in the early 1800s, he said, while the Ho-Chunk people were already well-established there.

The grounds of what is now UW-Madison’s campus do show traces of human occupation going back 12,000 years, Einstein said.

“This area in particular was a node,” he said, “a hotspot for human habitation. We have a whole lot going on here that would make life plentiful: the lakes, so you can have rice; fish, beaver, muskrat, transportation routes. Of course people were living here.”

Specifically in the Camp Randall area, Einstein isn’t aware of any evidence of early significant Native American activity. However, Einstein said there are archeological sites all around the Four Lakes region. And about 1,000 years ago, in the “Woodland Period,” he said we do know there was a lot of ceremonial activity, associated with a burial ritual — the construction of effigy mounds.

“We really haven’t embraced the specialness of this culture,” Einstein said.

The Ho-Chunk Nation say their ancestors built the mounds, he said.

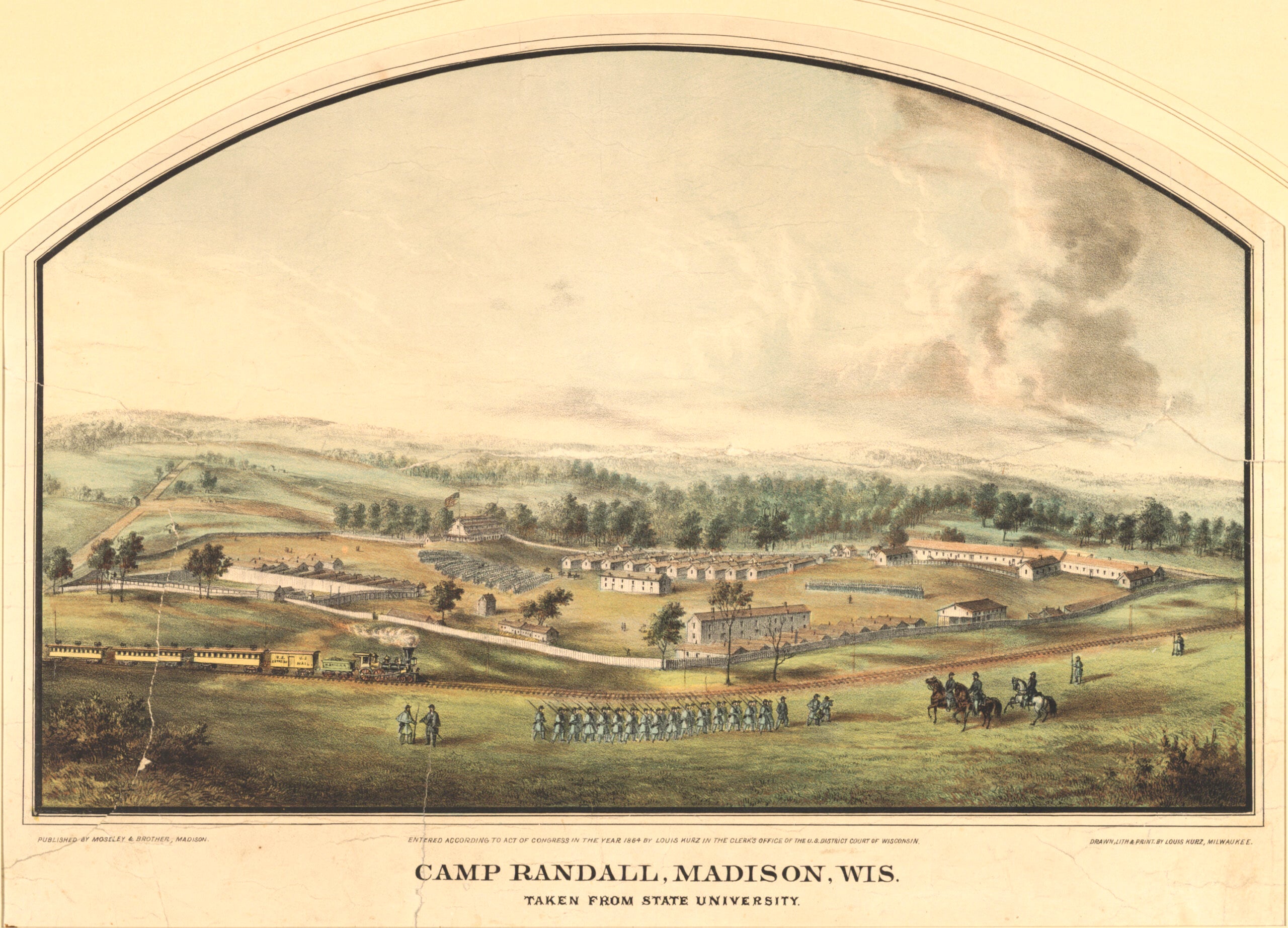

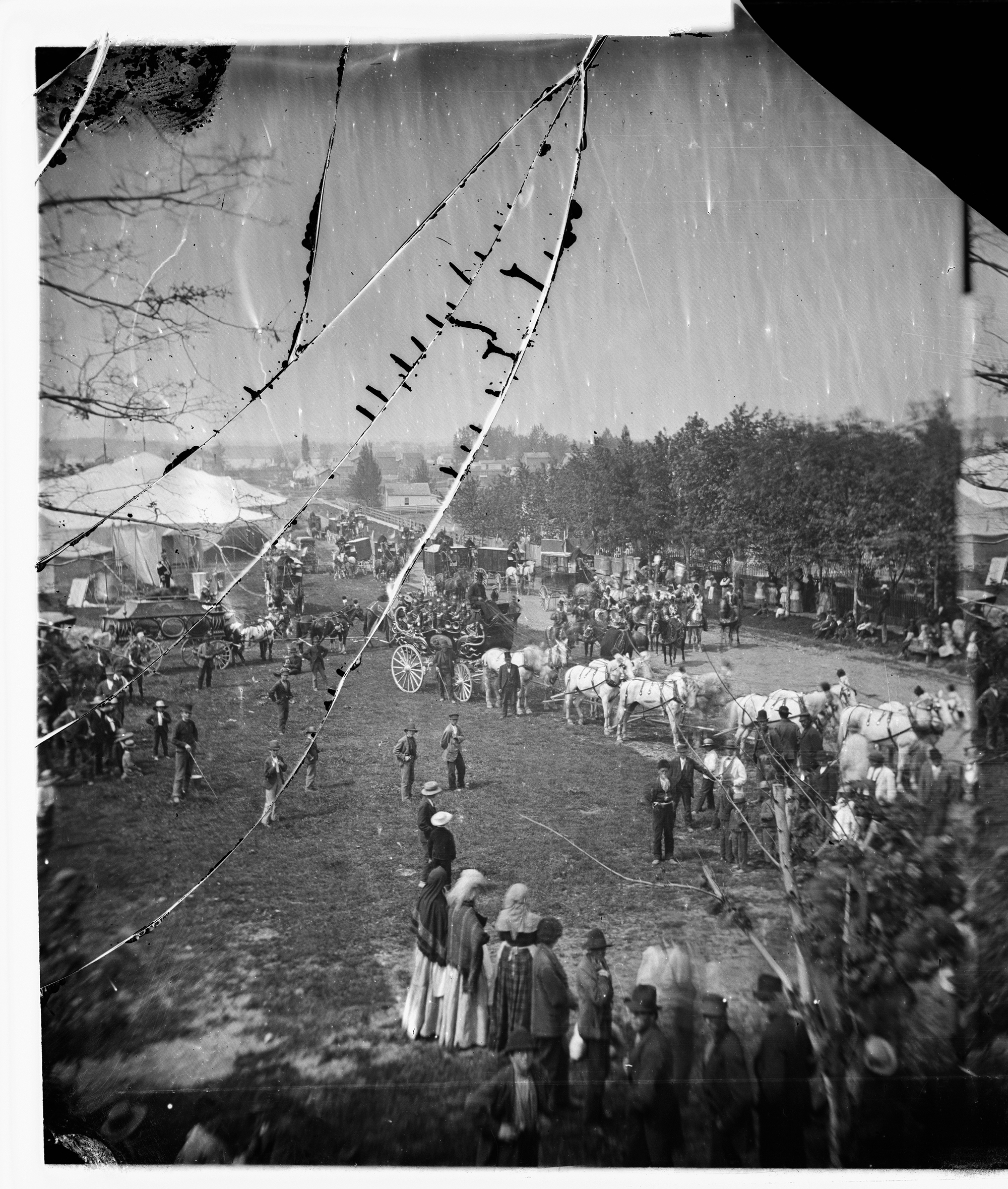

After Europeans arrived in the early 1800s, the grounds where Camp Randall now stands began to be used by the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society to host the Wisconsin State Fair, with the first one taking place in 1858, Einstein said.

Activities at the fair included plowing contests, equestrian cavalcades, and exhibitions that included inventions from naturalist John Muir.

In 1861, the federal government requested soldiers from northern states to help fight for the Union Army in the Civil War. Wisconsin Gov. Alexander Randall chose the fairgrounds as a place to train these recruits, and the camp would bear his name as a result. It was a 53-acre plot of land that covered “a pretty big chunk of what is now the UW-Madison campus,” said Einstein.

Einstein said more than 70,000 Wisconsin troops prepared for war at Camp Randall until the end of the war in 1865.

“That was fully three-quarters of all the soldiers that Wisconsin provided to the Union Army — a really significant military establishment here in Madison,” he said.

To accommodate up to 5,000 people at a time, the camp included 40 barracks, a hospital, officer quarters, stables and a commissary.

For one month in 1862, Einstein pointed out that 1,200 Confederate prisoners of war were taken to Madison and held at Camp Randall. Disease and wounds caused 140 deaths among that group. Those soldiers were buried in Forest Hill Cemetery on Madison’s west side. It was the northernmost burial site for Confederate soldiers in the U.S., Einstein said.

After the war ended, Einstein said, the Camp Randall grounds once again became state agricultural fairground. We also know, he said, the Barnum Circus held many events on the grounds before, during and after the war. And there are reports of a Native American lacrosse game being played on the fairgrounds in 1885.

[[{“fid”:”1371771″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EConfederate%20prisoners%20of%20war%20who%20died%20while%20being%20held%20at%20Camp%20Randall%20were%20buried%20in%20Forest%20Hill%20Cemetery.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20the%20Wisconsin%20Historical%20Society%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EConfederate%20prisoners%20of%20war%20who%20died%20while%20being%20held%20at%20Camp%20Randall%20were%20buried%20in%20Forest%20Hill%20Cemetery.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20the%20Wisconsin%20Historical%20Society%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”,”title”:”Confederate soldier graves at Forest Hill Cemetery”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

Twenty-eight years after the end of the war, in 1893, the state of Wisconsin purchased the property from private business owners. There had been talk of opening the grounds up to residential development. But “veterans approached the state and said that wouldn’t be right.” Einstein said, “To convert these hallowed grounds, this place where so many union soldiers were both mustered in and left military service.”

After buying the land, the government gave the property to UW-Madison for exclusive use. Starting in 1909, Einstein said, that use included a pharmaceutical garden that looked at the medicinal values of plants, such as cannabis.

Football players first took the field in the area next to the old fairgrounds grandstand in 1895, said Einstein, where the campus’s Engineering Hall is now located.

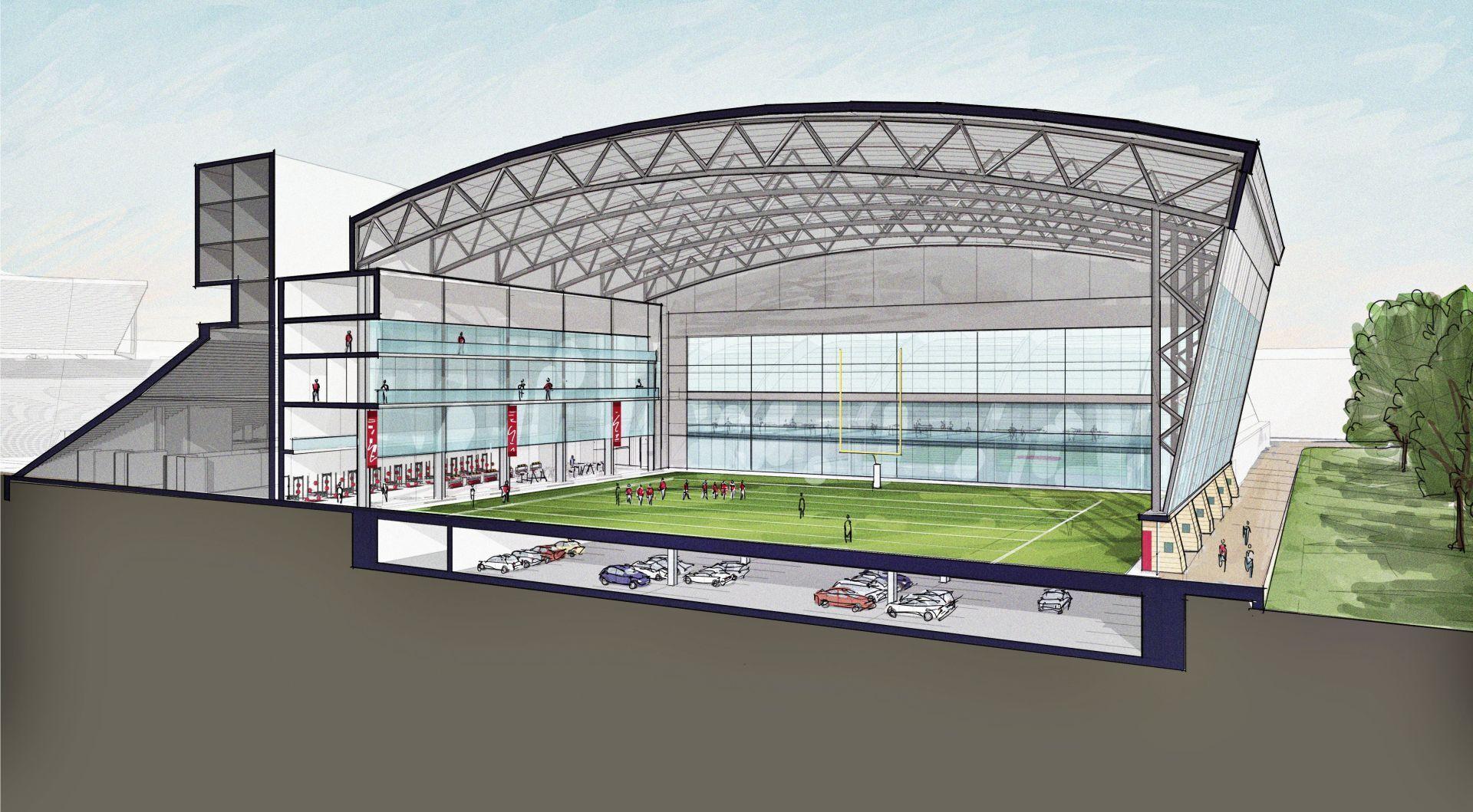

“The old grandstand had problems,” Einstein said. And after the bleachers collapsed, “in 1917, money was allocated to create a new stadium.”

With that new funding, the university built the first concrete seating structure into the side of Breese Terrace. That would be the western side of the new stadium. Einstein said since the first concrete bleachers, the stadium has been essentially evolving and morphing continuously — with additions in 1923, 1940, 1951, 1955, 1958, 1966, 1994, and 2005.

This story came from an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it in a future story.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify information regarding the grandstand and when the state purchased the property.