Charles Yu tackles racism through the lens of a fictional cop show in his novel, “Interior Chinatown.” Also, musician/author Will Birch gives us the lowdown on one of England’s greatest songwriters, Nick Lowe. And the doctor will see you now — Jonathan Katz on the return of his professional therapist character, Dr. Katz.

Featured in this Show

-

Charles Yu's Novel 'Interior Chinatown' Explores Racism Through The Lens Of A Cop TV Show

Charles Yu is probably best known for his critically-acclaimed novel, “How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.“

Yu has also worked as a writer for the FX series, “Legion” and the HBO series “Westworld.” This experience in television likely came in handy for “Interior Chinatown” — structured like a television script, the novel explores racism through the lens of the TV cameras that shoot the show.

Yu’s parents are immigrants from Taiwan who have lived over two-thirds of their lives in the United States as naturalized citizens. Yu has two children who are “reaching an age where they can ask questions” and “talk about things with classmates.”

“They have questions around their identity both in terms of where do their families come from, but also are they real Americans?” Yu told WPR’s “BETA“. “They see the news. They see questions about immigration and questions about race and ethnicity as well. I certainly think there are very important, weighty ways to write about race … but I wanted to at the same time have a different kind of approach. And I wanted to tell a good story that I hope is also entertaining.”

Curious what “Interior Chinatown” is about? Yu has come up with an elevator pitch for the novel:

“We’ve all seen ‘Law and Order.’ Every few seasons it seems they have a special episode set in Chinatown and you’ve got the two leads and they’re cops and they’re discussing the case. And they’re in the foreground and way in the back, almost out of focus is an Asian guy unloading a van. And I wanted to tell a story about that guy — van guy who doesn’t usually get a lot of lines and doesn’t usually have a name. But in my book he does have a name and his name is Willis Wu,” he said.

Wu lives in a single-room occupancy (SRO) building above a Chinese restaurant. Every morning, he goes downstairs to the Chinese restaurant where the procedural police show, “Black and White” is filmed. Willis portrays Generic Asian Man No. 3, but he dreams of playing Kung Fu Guy because that’s the ultimate position he can aspire to be in the world of “Interior Chinatown.”

It’s a very clever premise because it allows Yu to explore the racism that Asian Americans have experienced over the past 200 years through the lens of the TV camera that shoots “Black and White.”

Yu’s taken it a step further and even written the novel in the form of a teleplay script, complete with the standard screenplay font, Courier, which was initially created for IBM typewriters.

“Interior Chinatown” opens with an epigraph from Bonnie Tsui’s book, “American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods“: “If a film needed an exotic backdrop … Chinatown could be made to represent itself or any other Chinatown in the world. Even today, it stands in for the ambiguous Asian anywhere.”

Yu said he wanted to use that quote because while doing research for his novel, he discovered that Los Angeles’ Chinatown has a history of doubling as authentic Asian locations for many films.

Pedestrians walk under the rain in the Chinatown Plaza in Los Angeles on Friday, April 8, 2016. Damian Dovarganes/AP Photo “But really, what Bonnie Tsui’s getting at here in this quote is that it doesn’t stand for any specific location, it stands for kind of the idea of an Asian exotic locale. And the point being that as viewers of the thing that’s being filmed, we don’t care so much where that is. We just know it’s other,” Yu said. “I thought that was the perfect way in to describe what the Chinatown that Willis Wu lives in is like.”

Throughout writing the novel, Yu had the chance to explore his own cultural identity.

“My parents are immigrants from Taiwan and I have grown up listening to their stories and have tried in my own way to pass along some of that to my own kids. But as an American who was born and raised here, I have a really limited capacity to do that as a dad … my cultural knowledge is 80’s sitcoms and video games, among other things. And so it was about trying to explore cultural identity, but the specific cultural identity that I think I have as an Asian American.”

He continued, “In creating this character, I almost started to have a dialogue with a fictionalized version of someone that I could imagine knowing or someone that is drawn from parts of me. It is personal in some ways that I have often felt not part of the action or pushed into stereotypes. And until I wrote this book, I couldn’t quite articulate exactly what that feels like or why it matters.”

But in writing the book, Yu was able to articulate to himself why it matters.

Yu extends the screenplay approach in his novel to the acknowledgements section which he presents in the form of the end credits of a film. In these credits, Yu mentions the influence sociologist Erving Goffman’s book, “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life” had on his book.

“The framework that Goffman lays out is basically of the self as a kind of performance. And he talks about rules and he talks about communication out of character and regions,” he said. “If you imagine a stage, front stage and backstage, and how even in interactions as simple as like going to get coffee, waiting for an elevator or passing someone on the street, there’s a kind of performative aspect to what we show to people and what we hide from people.”

Yu gives an example of workers at a fast food restaurant rolling their eyes at a customer.

“Here’s Taco Bell, here’s the front stage of it. And then here’s the backstage of it. And that as a framework was I think the background of what ‘Interior Chinatown’ is trying to do is saying, ‘Yes, self is a kind of role.’ And then on top of that, what about an Asian American consciousness? On top of that and then where it got more exciting to me was not just that Willis is playing a role, but that all of these characters, black, white, Willis’ parents, even the children are playing roles,” he added.

While exploring the Asian American experience in the U.S. for his book, other forms of pop culture highlighting Asian characters began gaining traction.

“Crazy Rich Asians” was a huge hit at the box office when it came out in 2018.

And this year, Awkwafina won a Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Comedy or Musical for “The Farewell,” making her the first woman of Asian descent to win a Golden Globe in a lead actress category.

“BETA” asked Yu if he thinks these are signs Hollywood is finally giving Asian Americans the opportunities they deserve?

“I feel like there’s real progress being made,” he said. “I do wonder though … with ‘Crazy Rich Asians,’ that’s really a movie about Asians, not Asian Americans, you know. And they’re very rich. And so it’s this beautiful fantasy. And I was very entertained by the movie. But that’s a different kind of story.”

“With ‘The Farewell,’ which I loved that movie, … again, it’s an American going to China. And the movie takes place in China,” Yu explained. “What I’m curious to see, are there going to be stories where Asian Americans can be part of the actual reality we see on screen the way they are in actual reality?”

-

The Many Lives Of Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist

Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist — the character that Jonathan Katz made famous and vice versa — has gone through several permutations over the years.

Co-created with late-night legend and comedy writer, Tom Snyder, Katz’s premise has gone from a standup bit to the hit mid-90s Comedy Central animated TV show to a podcast to a live stage show and has now settled into the medium of audiobooks.

“There has been all kinds of iterations of Dr. Katz,” Jonathan Katz tells WPR’s “BETA.” “To me, when we did the cartoon it always seemed like this wonderful radio show.”

That’s why the leap to audio was such a seamless transition.

“Dr Katz: The Audiobook” carries on with the simple, but brilliant premise of a celebrity therapist, voiced by Katz, with a patient list full of problem-ridden comedians.

“We started with the biography of Mr. Katz, which was also fun, but it’s just me doing my act and talking to a biographer voiced by this woman named Julianne Schapiro, who played Julie in the Dr. Katz TV show,” Katz said. “That had kind of a limited potential, we realized, and so we settled on the idea of therapy, because you have traffic passing through your office and especially (if) there were comedians, that could be wonderful.”

The Comedy Central animated series became a hit for the network. Known for its improvisational tone and trademarked squiggly animation, it featured a Who’s Who of popular comedians and actors of the time including: Ray Romano, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Dave Attell, Joy Behar, Wendy Liebman, Steven Wright, Jim Gaffigan and Dom Irrera.

There’s something inherently organic about comedians populating a therapist’s office.

“I think that they’re very vocal about their unhappiness, often on stage,” Katz said.

Essentially the show served as another vehicle to showcase their material, but it was fleshed out by the playful banter between Dr. Katz and his talkative and aimless son, Ben, who was voiced by H. Jon Benjamin.

The role would launch Benjamin’s career as he would go on to take lead voice roles in the animated hits “Archer” and “Bob’s Burgers.” Katz insists that Benjamin remains one of the funniest people on the planet.

“He comes at comedy from a totally different angle than me. And nobody can write for Jon Benjamin because he’ll just say something funnier,” Katz said. “Any rules you think that exist in improv don’t exist for him. We spent so much time just laughing out loud, so hard.”

In fact, Benjamin is one of the only people to make Katz faint. Katz said they were in a Japanese restaurant in Los Angeles. Katz was attempting to enjoy a nice bowl of miso soup when Benjamin made him laugh so hard the next thing he remembers is waking up to his worried wife.

“The combination of soup and laughing doesn’t work,” joked Katz.

The two reconnect for the audiobook, which again features many familiar faces (or voices) and some new “patients” like Jon Hamm, Jen Kirkman and Demetri Martin.

“Boy is (Martin) funny. He’s so wonderful. He says he’s not superstitious, he thinks he has the regular amount of stish,” laughed Katz.

While Katz has had no issues procuring comedic patients/guests for the various versions of Dr. Katz, he does still have a wish list.

“I was thinking about Lily Tomlin the other night, that she would be fun to have on the show,” he said.

Katz didn’t base his popular character on one specific therapist from his life, but he did invite several real therapists on to the show often as consultants. Additionally, he jokes that his hometown was no stranger to psychiatry.

“I was living in Newton, Massachusetts, which has the highest number of therapists per capita of any city in the country. In fact, in Newton, if you run outside and scream, ‘You have issues,’ somebody will toss you a bottle of Prozac,” he said.

And while Katz didn’t base his character on a real life persona, he did incorporate some of his familial issues into the show and audiobook. Like, how he handled his daughter’s inquiries about being an only child, which he reworks and develops for a bit with his son Ben.

“She was the only child in her class for many years, and she asked me why that was. And I said, ‘Look, Julie, you have a sister, but you’re always missing her by about five minutes.’”

Spending a bulk of your career playing a fictionalized character who is known mainly for his voice and animated avatar might lead to some identity issues that you couldn’t be blamed for wanting to vent about to someone like, well, Dr. Katz.

“I do have a certain envy of Dr. Katz, even though you could argue that he is me, he’s so much better known than I am,” Katz said. “I think that’s the experience most cartoon characters have, is that nobody recognizes them, but it’s painful — the difference between the popularity of Dr. Katz and Jonathan Katz.”

Outside of the celebrity arena, it’s a bit of a different story.

“On the other hand, when my grandchildren see me, they are thrilled that it’s me and not Dr. Katz,” Katz said.

You know what that music means. Our time is up.

-

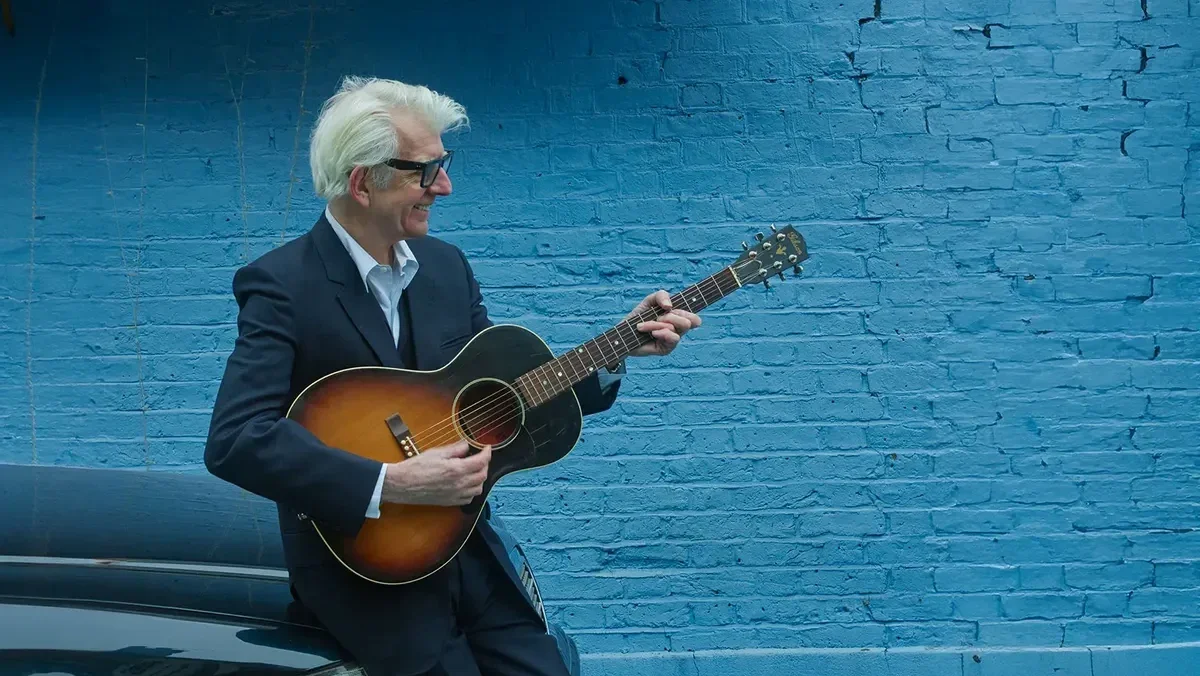

Why Singer-Songwriter Nick Lowe Reinvented His Sound

During the 1970s, Will Birch was a drummer for The Kursaal Flyers and The Records. He later became a record producer. Now, Birch has written the definitive biography of Nick Lowe.

Lowe pioneered pub rock, power pop and new wave. He’s best known for his songs “Cruel To Be Kind” and “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love and Understanding.”

Dubbed the “Jesus of Cool,” Lowe is also known for his production work for Elvis Costello and his successful turn into a more stripped-down singer-songwriter. Birch chronicles Lowe’s career in “Cruel to Be Kind: The Life and Times of Nick Lowe.”

“I think that Nick’s influences obviously are early country music,” Birch told WPR’s “BETA.” “When he was a boy (in the 1950s), he grew up living to a large extent on Royal Air Force bases in Europe when his father was an officer in the Royal Air Force. So he did a lot of traveling as a child, and he often stayed at air bases where there were American airmen stations.”

Birch explained that the radio stations at these air bases played music for the airmen. Then when Lowe attended school and college, he mixed with the crowd that was interested in mid-1960s soul music, such as James Brown, Sam & Dave, Otis Redding and The Temptations.

“So he was doubly exposed to both black and white American music,” Birch explained. “And as he has said himself, I think some of his aspirations are to sort of fuse those two genres, if you like, to produce something of his own that’s unique.”

Lowe spent nine years as a member of the country, blues-rock band, Brinsley Schwarz. After leaving the band in 1975, Lowe launched a solo career with the release of “So It Goes” backed with “Heart of the City” in August 1976. This was the first single on the indie label, Stiff Records.

Birch said Lowe’s first two songs are very good but quite different in style.

“It’s not too hard to detect the influences,” Birch said. “I don’t want to accuse Nick of stealing, let’s say, some of his tunes, but he’d be the first to admit he is influenced. And in ‘Heart of the City,’ you do hear quite a bit of the influence of Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers’ ‘Roadrunner.’ But Nick made it his own.”

It was around this time that Lowe formed the band Rockpile with Welsh guitarist, singer and producer Dave Edmunds and guitarist-singer Billy Bremner and drummer Terry Williams. One reviewer described the band as being fueled by the same energy source as the punks but being able to play rings around them.

“I would say if you want straight-ahead, fast rock ‘n’ roll with great guitar licks, harmonies and a fantastic, swinging drummer, I still don’t think there’s anybody on the planet who could have beaten Rockpile and probably not today. They were very, very exciting live.”

Lowe’s second solo album, “Labour of Lust,” was released in June 1979, and featured accompaniment by Rockpile.

The album featured Lowe’s hit single, “Cruel to Be Kind,” which ended up being his most successful American single. Lowe had actually written the song with band mate Ian Gomm during their Brinsley Schwarz days. Birch said Lowe has told him the original version of “Cruel to Be Kind” was heavily influenced by the sound of the American soul and R&B group, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. It was record company executive Gregg Geller who suggested Lowe and Rockpile record another version of “Cruel to Be Kind,”

“It really, really benefited from Dave Edmunds’ production skills and vocal harmonies and backing arrangement, whereas Nick might have sort of shied away from putting too much icing on it,” Birch said.

The music video for the song was one of the first videos to air on MTV. It’s a combination of real footage of Lowe’s marriage to Carlene Carter, daughter of June Carter and stepdaughter of Johnny Cash, along with a reenactment of the actual wedding ceremony.

Lowe received a financial windfall after one of his early songs, “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love & Understanding,” was featured on the soundtrack to the 1992 movie, “The Bodyguard,” starring Whitney Houston and Kevin Costner.

It was a cover version by the American jazz singer Curtis Stigers.

“Curtis’s version went on the soundtrack album, and that album went on to sell millions and millions,” Birch explained. “In fact. If you look it up, you’ll find Arista Records claim it sold 45 million units worldwide, So one day the postman turned up with a rather large check for Nick.”

This unexpected payday allowed Lowe to spend much more time writing and recording his songs. The result was a new sound, which combined country and soul influences in a much more intimate manner. One of the most intriguing songs from Act Two of Lowe’s career is a song called “I Trained Her to Love Me.”

“It’s one of my absolute favorite songs of Nick’s,” Birch said. “It was just a fantastic twist on relationships. And it’s quite audacious. It’s quite conceited, really. But with his tongue a little bit in his cheek, but not too far to take it to the level, where, ‘Well, I made her love me so I could then ditch her.’ is quite conceited, but it’s got enough humor in it that he can just about get away with it.”

“I remember the first time I heard that, it was a concert in London. He was singing solo acoustic in a big hall, The Barbican Theatre maybe, a couple of thousand people in the audience,” he continued. “And he put it in the middle of his set and you could hear a pin drop. As you sat there listening to this song being sung to the audience, probably for the first time, there were men and women around, you could feel people like tightening up with, ‘What’s he saying?’”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Doug Gordon Interviewer

- Charles Yu Guest

- Will Birch Guest

- Jonathan Katz Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.