Beth Mullen-Houser’s household gets their flu shots every year before the holidays. The La Crosse family keeps up to date on all their other vaccines, as well.

Mullen-Houser is a clinical psychologist with a science background, so she’s well-versed in the public health benefits of vaccines — not just to her family, but to everyone they come in contact with.

“I think it’s always a pretty big risk to not vaccinate when you could, physically,” she said, “especially to the people who are most vulnerable, who can’t vaccinate.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Many discussions on a true return to “normal” — not just the phased, socially-distanced reopening of bars, restaurants and summer camps that’s started in Wisconsin and around the world, but an actual rooting out of the virus — revolve around a vaccine that could be several years away.

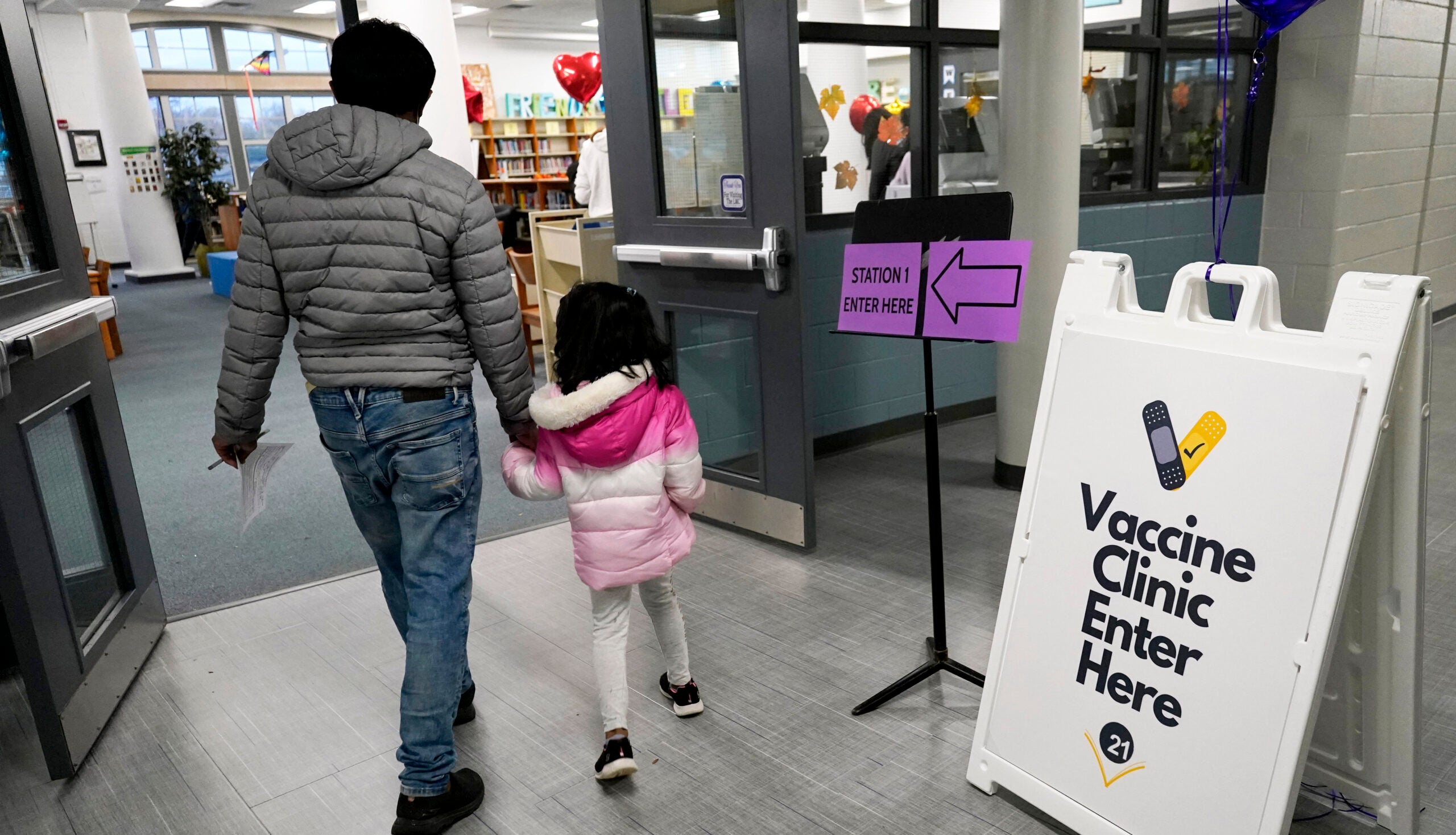

That got Mullen-Houser thinking about what happens when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available. She wrote into WPR’s WHYsconsin asking whether it would be required in public schools, like DTaP, measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), and tetanus are now — and what that process would look like.

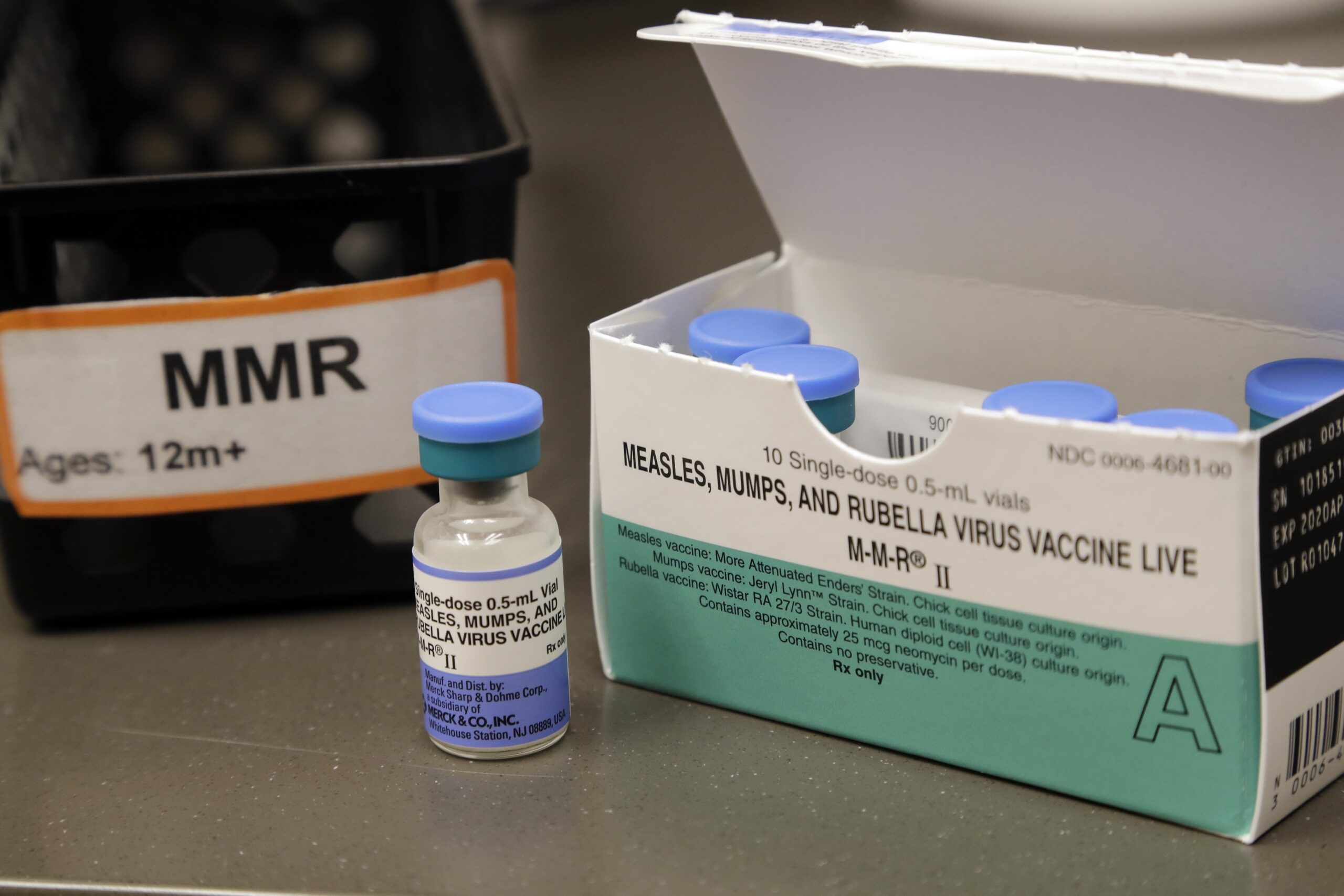

At present, Wisconsin law and administrative rules include immunizations against a dozen illnesses for kids going to schools, day cares and nursery schools — everything from whooping cough and measles to tetanus and Hepatitis B.

That means Mullen-Houser’s 9-year-old son, a student at School of Technology and Arts 1 in La Crosse, has had to show his school proof he’s up to date on his shots.

“No one is forced to get vaccinated,” said state Assembly Democratic minority leader Gordon Hintz, “but the decision to allow you in our schools — you don’t have the right to jeopardize the lives and health of other children.”

However, families can opt out of vaccination under three exceptions: medical necessity, religious belief, and personal conviction. The last category is the broadest, and is the most common reason parents cite for opting their kids out.

Other states have eliminated their personal conviction exemption. Washington, for example, closed that loophole for MMR in 2019 after a series of measles outbreaks. Wisconsin is now one of only 15 states where parents can opt out because of personal conviction.

Wisconsin lawmakers, including Hintz, attempted to end the personal conviction exemption in 2019, but were unsuccessful.

“A year ago, there were all these rallies, and I was getting attacked, and it seemed to be that people were questioning the value of vaccines,” Hintz recalled. “Everybody’s hopes are now rallying around the very idea of (a vaccine).”

New vaccines can be added to Wisconsin’s list of required immunizations either by the state Legislature or the Department of Health Services (DHS). Each school year, DHS publishes a list of school immunization requirements, which this year included polio, MMR and Tdap.

A COVID-19 vaccine would also have to be approved by the state Legislature or DHS to be added to the list of vaccines required for kids in schools and day cares.

George Morris, president of the Wisconsin Medical Society and a practicing physician at Ascension Columbia St. Mary’s in Milwaukee, said he expects the eventual COVID-19 vaccine to be added to that requirement.

“I do think we absolutely can and we will mandate it,” he said. “The question will be, what do we choose to do about personal exemptions? That will be the test.”

In order to reach effective herd immunity, meaning that enough of the population is vaccinated that people who can’t or won’t get vaccines are also protected, a high percentage of the population needs to not opt out. The percentage of people who need to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity varies based on the disease. For measles, which is particularly contagious, that threshold is high — between 93 and 95 percent.

According to a Pew Research Center study published last month, about 72 percent of Americans said they would definitely or probably get a COVID-19 vaccine if one were available.

For Hintz, the lawmaker, herd immunity isn’t just a political priority, it’s a personal one. He has an 11-month-old baby who may not be old enough to get the vaccine once it’s available.

“We don’t vaccinate to protect ourselves, we vaccinate to protect others and those who can’t,” he said. “It’s a lot of the parallels that we’re seeing in the COVID fight — you know, we don’t wear masks necessarily to protect ourselves, but it’s to protect from the transmission of the virus to others.”

But getting to a point where Wisconsin could require a vaccine might be its own challenge.

The efforts to contain, test for and treat COVID-19 have revealed shortages in everything from the swabs needed for testing to masks to ventilators. Scaling a vaccine up to widespread use, especially with the whole world trying to get enough doses, could be hampered by similar shortages.

Even when it’s tested, approved and available, some people might be skittish about a vaccine whose effects haven’t been monitored for as long as the more familiar measles, chicken pox and mumps vaccine. WHYsconsin questioner Mullen-Houser said she’s a little nervous about having her son get a shot that’s been fast-tracked to approval.

“As a parent, even though I really, really do believe in vaccines, I want to make sure it is a safe one before we would have any of us take it, especially my son,” she said.

Morris, the physician, said he’s confident the vaccine testing and approval process, even if it’s accelerated, will screen out possible vaccines that pose a risk.

“There will be less than a 1 percent risk of something happening, because we will have tested enough individuals to be able to say that,” he said. “These vaccines will be received by hundreds of people, and they’ll be very carefully screened for adverse effects.”

Hintz also feels good about the safety of an eventual vaccine — and is hopeful the COVID-19 epidemic, and an eventual vaccine to address it, could open the door for more vaccine-skeptical Wisconsinites to see vaccines as a safe means of promoting public health.

“If we get it right, and we put it through the traditional course, I think the public will understand that the testing is rigorous and thorough, and hopefully will restore some of the trust in folks that are vaccine-reluctant.”

Editor’s note: Information presented in the timeline above was compiled by Ryan LeCloux, a legislative analyst from the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau.

This story came from an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your questions or concerns about COVID-19 here and we will do our best to answer it.