In this Wisconsin Public Radio series, “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” WPR reporters explore how the state’s 1849 abortion ban came to be and how Wisconsinites have lived with and without it since.

__________________________________________________________________________

On a Saturday in September 1969, a 23-year-old grad student walked into an office inside the Majestic Building in downtown Milwaukee. She had been there once before, for a consultation with Dr. Sidney Babbitz.

Babbitz was 59 years old and had mostly retired to Florida. But he was known in whisper networks as a doctor who was willing to perform illegal abortions back in Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The woman handed Babbitz a stack of 18 $50 bills — $900 total — and Babbitz gave her an abortion.

On their way out of the office, Babbitz saw a police officer in the hallway. He told the woman to go back into his office and gave her some pills he said he had forgotten. When they thought the coast was clear, Babbitz took the elevator with her down to the building’s lobby. Another police officer was there waiting for them.

What happened next led to a yearslong legal battle, one that eventually upended more than a century of abortion law in Wisconsin.

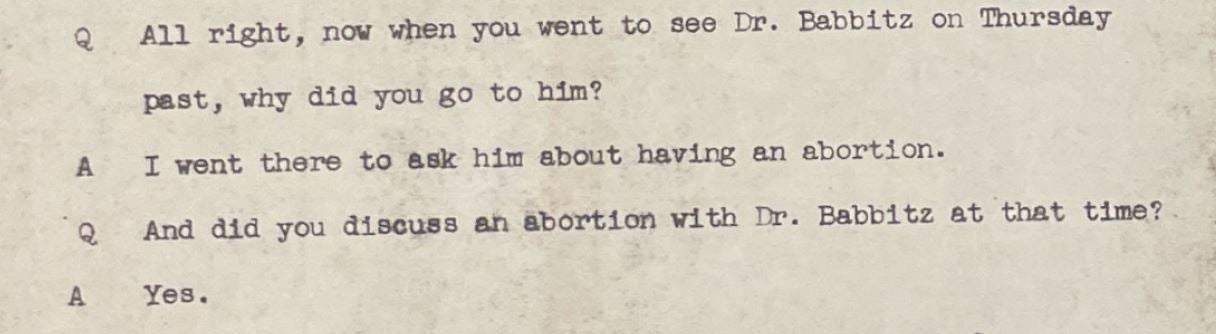

Only hours after her abortion, prosecutors got the woman to appear in a Milwaukee County courtroom. Initially, she declined to answer questions. At several points, a transcript shows, officials had to ask her to speak up.

After the judge gave her immunity from prosecution, she described how Babbitz used dilation and curettage to terminate her pregnancy at about nine weeks. Her testimony was enough for a judge to grant a warrant to search Babbitz’s office.

That led to the doctor’s arrest, which would spiral into a lawsuit. In 1970, that suit led a federal court to strike down much of a Wisconsin law that had banned abortions.

A few years later, the Babbitz verdict was overshadowed when the U.S. Supreme Court established federal protections for abortion through Roe vs. Wade in 1973.

But, now, more than a half a century since the court decision, the Babbitz case may have new relevance.

Clinics across the state stopped performing elective abortions after Roe was overturned in June 2022. That’s when the state reverted to a long-dormant 19th-century law that’s widely interpreted as banning abortions unless they’re done to save a pregnant patient’s life.

Just days after Roe was overturned, Wisconsin’s Democratic Attorney General sued to try and block prosecutions of abortions under that law, which is the same law used to prosecute Babbitz more than half a century prior.

The AG’s ongoing lawsuit briefly references the Babbitz case, noting that a federal court has previously found the law to be unconstitutionally overbroad.

For newly elected prosecutor, opposition to abortion is personal

When a U.S. District court issued a declaratory judgment in Babbitz’s favor in 1970, the ruling was a watershed victory for Wisconsin’s growing abortion-rights movement.

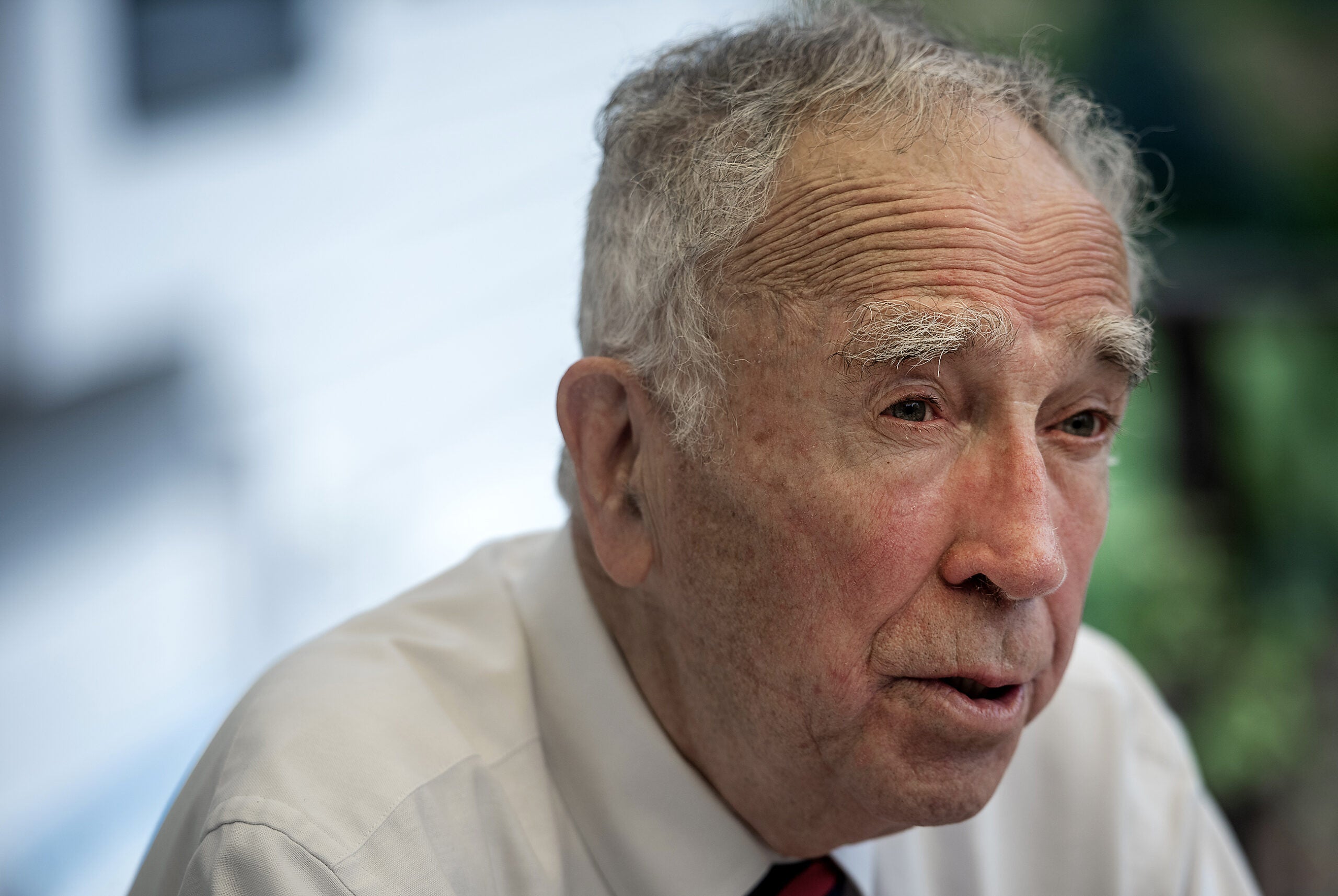

But for E. Michael McCann, it was a blow that was both professional and personal.

McCann had been Milwaukee County District Attorney for less than a year when he got a tip that Babbitz would be performing an abortion at his office. That led to the stakeout at the Majestic Building, the questioning of the young woman and to McCann charging Babbitz with a felony.

McCann, now 86, is a lifelong Democrat and a devout Catholic. He’s open about how his faith informs his politics — everything from his opposition to abortion and the death penalty to his support of social programs that assist the poor.

“I have, I guess, a deep respect for human life,” McCann said in an interview at his home, “and a suspicion that … whenever human life is diminished, there’s a price paid for it.”

For McCann, the case against Babbitz was straightforward. Abortion had been mostly or entirely illegal in Wisconsin since the state was less than a year old, with the first law restricting abortion passed in 1849. McCann had ironclad evidence that Babbitz had performed an abortion.

“We were not thinking we would find some brand new case law coming up, some new theory of law,” McCann said.

Babbitz died in 1984. Members of his family declined to speak with WPR or did not respond to requests for comment.

The woman who went to Babbitz for an abortion did not respond to requests for comment; she was never charged with any crime and WPR is not naming her.

Legal historian Mary Ziegler, who has written extensively on abortion and the law, said the women who received abortions weren’t typically the ones prosecuted. But prosecutors sometimes used the threat of legal trouble to pressure women into testifying against medical providers.

“Instead of actually prosecuting women, they would say, ‘We won’t prosecute you if you turn state’s witness,’” Ziegler explained.

It’s not clear from the hearing transcript whether the woman had a lawyer during the hearing that took place on the same day she had her abortion — the one where a judge granted a warrant to search Babbitz’s office.

She did have an attorney by the time she testified at a preliminary hearing in December 1969, so that the judge could establish probable cause for the charge against Babbitz.

Before that court appearance, she visited another doctor at the urging of prosecutors, where she underwent a vaginal examination. That doctor testified about his clinical observations during the hearing, so that prosecutors could establish the woman was no longer pregnant and had likely had an abortion.

These facts were never disputed. But in the end, the case became about a broader constitutional question. Babbitz sued and a panel of three federal judges took up the case. That forced the state to defend the abortion law itself.

“The issue became, you know, what were her rights?” McCann said. “Did she have a right to have an abortion? If she had a right to have an abortion, then Babbitz had not violated the law by giving her an abortion.“

As grassroots activism takes off, a Milwaukee-area housewife joins the fight

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, campaigns to legalize abortion were growing all over the country. But compared to today, views on abortion were less aligned with political parties. Historian Dave Garrow says abortion-rights groups were mostly grassroots.

“Opposition to abortion was by no means a Republican issue, nor was abortion rights a unanimously Democratic issue,” said Garrow, whose book “Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe v. Wade” looks at the legal and cultural movements for abortion rights. “These local efforts were surprisingly uncoordinated at any national level or by any nationwide organization.”

In Wisconsin, one of those local leaders was Edith Rein.

Rein was a stay-at-home mother of two young daughters in suburban Milwaukee’s Whitefish Bay when she watched the 1965 documentary “Abortion and the Law,” which delved into the risks faced by women who had illegal abortions.

Already active in the Milwaukee chapter of the American Humanist Association, which advocates for a separation of church and state, Rein discussed with the group how they might push for abortion rights.

“Everybody was very happy to do something, except nobody wanted to do it publicly,” Rein said. “Everybody was so afraid. So I said, OK, I’ll do it.”

She founded the Wisconsin Committee to Legalize Abortion, appearing on radio and TV to debate the issue. She organized demonstrations in support of legalizing abortion, and urged support for the efforts of liberal state Rep. Lloyd Barbee, D-Milwaukee, who introduced bills to legalize abortion in Wisconsin in 1968 and 1969.

Something else happened once when Rein became a public advocate of abortion access: Her phone started ringing.

“I started getting phone calls from people asking if I knew where to get an abortion,” she said. “And I didn’t know. And then one day I got a phone call from somebody anonymous who gave me a phone number and said, ‘You can give this phone number and people can get abortions.’”

Soon, Rein was part of the underground network connecting women to abortion services. She took calls at all hours, from sometimes-desperate people.

“You hear every story on earth,” said Rein, now 89. “I would get so emotional hearing some of these stories. … A lot of the women who called would say to me: ‘I have so many kids, I can’t deal with another one. And my husband will not use birth control.’”

Selling birth control to unmarried people was illegal in Wisconsin until 1974. Even married women could have trouble getting it without their husbands’ permission.

When she was interviewed by the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1970, Rein told a reporter she never gave women instructions for doing anything illegal.

But, now, Rein readily admits that wasn’t true. She used to send women to Babbitz and other doctors, many of whom did abortions secretly.

More than 50 years later, Rein has few memories of Babbitz himself. But her group submitted an amicus brief on his behalf in the 1970 case and she remembers being in the courtroom during oral arguments. She was unimpressed by Babbitz’s lawyers, but said it became clear during the hearing that the judges would side with them.

“The judges actually helped them,” she recalled. “They practically put words in their mouths.”

Babbitz’s lawyers tried a number of different approaches. They argued Wisconsin’s law was too vague. They said the ban violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, because rich women could get abortions more easily than poor women. They even raised concerns about overpopulation.

Ultimately, the judges were most persuaded by arguments for a right to privacy in the Ninth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court had determined in Griswold v. Connecticut that privacy considerations protected the right of married couples to use contraceptives without interference from the government. In 1967, the justices again cited privacy rights when they handed down Loving v. Virginia, which made it illegal to outlaw interracial marriage.

By the late ’60s, Garrow said attorneys across the country were citing those rulings to argue for abortion rights in cases including Babbitz and eventually Roe.

“Roe v. Wade was by no means a singular case,” Garrow said. “There were dozens and dozens of these cases, including Babbitz from Wisconsin, from all around the country.“

Authorities raid Madison abortion clinic even after judges protected abortion access until ‘quickening’

The three-judge panel hearing Babbitz’s case in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin concluded the right to privacy protected the right to abortion up until the time of quickening. That’s whenever a pregnant person can feel the fetus’s movement, usually between 16 and 20 weeks into pregnancy. The U.S. Supreme Court would discuss a similar concept in Roe v. Wade when it granted the right to abortion prior to fetal “viability,” defined then as 23 or 24 weeks.

Effectively, the Babbitz ruling made part of Wisconsin’s century-old abortion ban unconstitutional.

Activists like Rein celebrated. The Milwaukee-based counterculture newspaper Kaleidoscope wrote that “the decision itself might as well have been written by a far out women’s liberationist.”

But the victory was complicated. Initially, the federal court declined to order the state to halt its prosecution of Babbitz.

Babbitz’s case was tied up in appeals for years. In the meantime, McCann and then-Wisconsin Attorney General Robert Warren, a Republican, kept moving forward in their attempts to bring Babbitz to trial.

The ongoing legal proceedings created an environment of uncertainty, which had ripple effects across the state.

In 1971, Dr. Alfred Kennan opened the Midwest Medical Center, a clinic that provided abortions in Madison. Just months after it opened, police got a warrant to search the clinic.

Annie Laurie Gaylor was 15 years old and living in Madison when Dane County District Attorney Gerald Nichol charged Kennan and four of his aides with violating Wisconsin’s abortion law.

“That was a scary time,” Gaylor said. “It felt like a police state or something that the DA could raid a legal clinic and take all the records.”

Gaylor’s mother, Anne Nicol Gaylor, was an abortion-rights activist who worked with Rein.

After Kennan’s arrest, Anne Nicol Gaylor spent days standing outside the Midwest Medical Center to let any patients who showed up know the clinic had been shut down. More than 300 patients had appointments pending with Kennan at the time of the raid, and activists tried to help those women get abortions elsewhere, including New York.

Eventually Kennan prevailed, and the charges against him were dropped. His attorneys argued abortion had been legal in Wisconsin since the Babbitz decision in 1970.

Kennan was allowed to reopen his clinic and to keep his medical license, though not before Anne Nicol Gaylor was subpoenaed by Wisconsin’s Board of Medical Examiners about her work referring people for abortions.

Later, when Annie Laurie Gaylor was in her early 20s, she joined forces with her mother to establish the Freedom from Religion Foundation, which advocates for the separation of church and state. Annie Laurie Gaylor said they were motivated, in part, by their encounters with religious opposition to abortion.

Today, Annie Laurie Gaylor is 67 years old. She still has vivid memories from the ’60s and ’70s of following her mom around the country to advocate for abortion rights.

“I would often be left at a pro-choice table and I was 13, 14, 15,” Gaylor remembered. “Invariably, some middle-aged or older man would come over indignant and say, ‘If some 16-year-old tart goes out and gets herself pregnant, you know, she shouldn’t be off the hook. She should have put an aspirin in between her legs.’”

Decades later, Gaylor can’t bring herself to read the full Supreme Court decision overturning Roe. It makes her too angry.

She worries that, in many ways, Wisconsin is headed back to the ’60s.

But, in Wisconsin, abortion-rights advocates hope history will soon be repeated in a different way.

In July, a Dane County judge ruled that AG Kaul’s lawsuit can proceed. The suit is an effort to block prosecutions of abortions under the same law that led to Babbitz’s 1969 arrest. It’s likely the case will make its way to Wisconsin’s Supreme Court, where liberals have gained a narrow majority after newly-elected Justice Janet Protasiewicz took office this month.

Advocates hope judges will toss out Wisconsin’s near-total ban on abortions, just like they did in 1970.

For more from “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” visit wpr.org/1849.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Anne Nicol Gaylor’s name.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.