In this Wisconsin Public Radio series, “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” WPR reporters explore how the state’s 1849 abortion ban came to be and how Wisconsinites have lived with and without it since.

__________________________________________________________________________

Last summer, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the legality of abortion was sent back to states — immediately reviving Wisconsin’s pre-Civil War abortion ban.

Few if any states reverted to laws as old as Wisconsin’s. Over the nearly 50 years the ban was unenforceable, why had lawmakers never revoked it?

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In some ways, the answer is simple: There was never the political will. And in the years immediately following the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the political lines when it came to abortion were blurred. It would take nearly a decade for the major parties in Wisconsin, and the nation, to begin to adopt unified stances on abortion.

And even as those stances coalesced, Democrats never amassed the legislative majorities they would need in Wisconsin to revoke the ban.

The first significant post-Roe abortion legislation in Wisconsin was a bipartisan bill to restrict the procedure.

Rep. Joanne Duren of Cazenovia was a Democrat, a devout Catholic and a passionate abortion opponent. She shepherded the 1978 proposal, which would prevent people from using Medicaid to pay for abortions, through months of legislative wrangling.

“This will move the state from an economic policy of killing human life to a policy which favors child-bearing and childbirth,” Duren told colleagues during one of the lengthy debates on the bill.

Democrats held two-thirds supermajorities in both the Assembly and the Senate — but they were deeply divided on this issue. Nevertheless, Duren was optimistic the proposal would pass.

Religious organizations and church leaders supported the plan, calling and writing lawmakers and showing up to testify at hearings. A sizable majority of lawmakers, it appeared, was ready to listen.

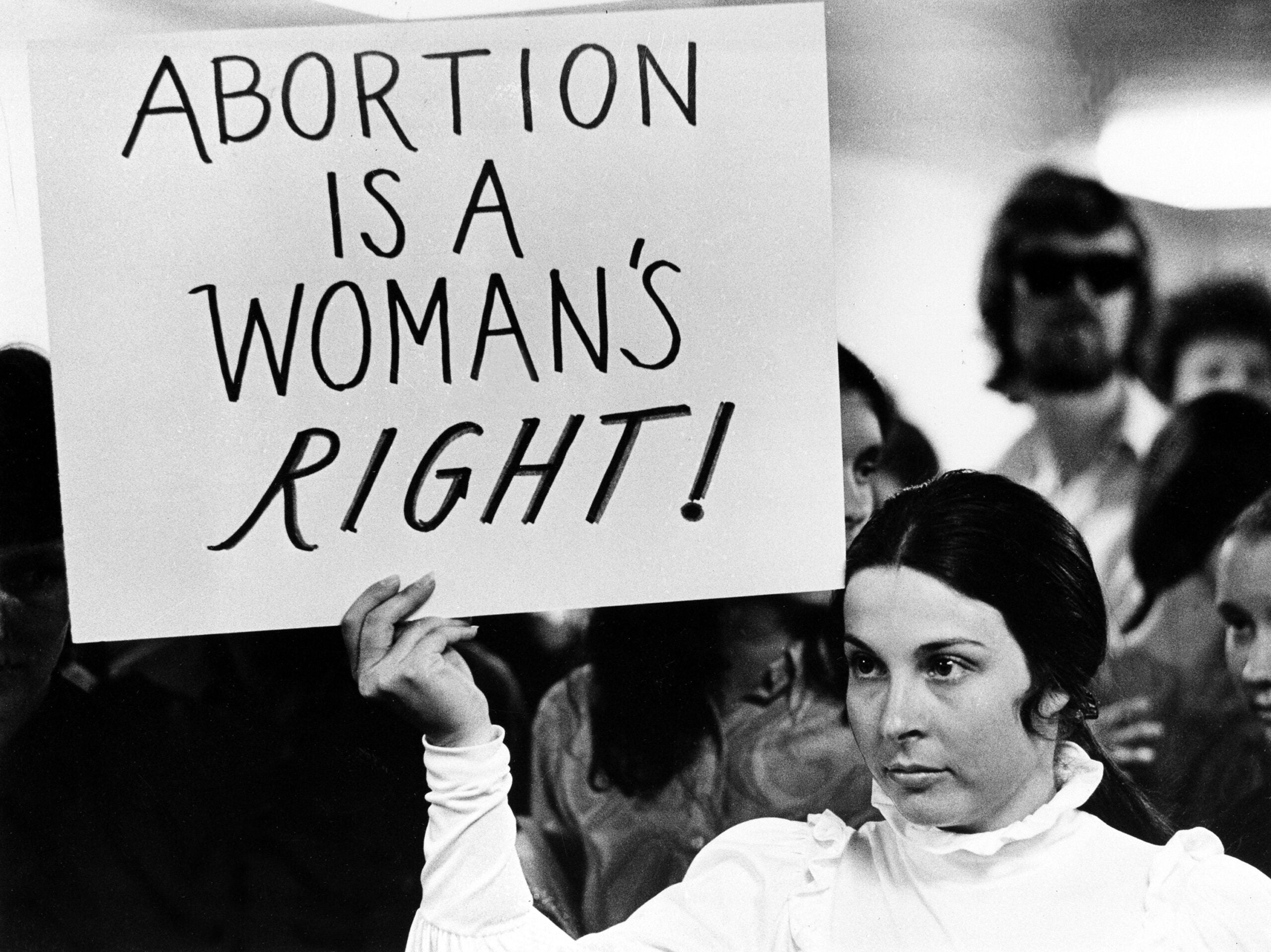

Abortion rights activists hoping to stop the bill descended on Madison, shouting at lawmakers in the Assembly and Senate. They were ejected from the chambers as some threw pipe cleaners shaped like coathangers from the galleries, a reference to a crude instrument sometimes used for dangerous, self-induced abortions.

“You’re killing women,” a protester shouted, according to newspaper coverage of the time.

Down on the floor, emotions among lawmakers also ran hot. One suggested government funded abortions would empower promiscuous women.

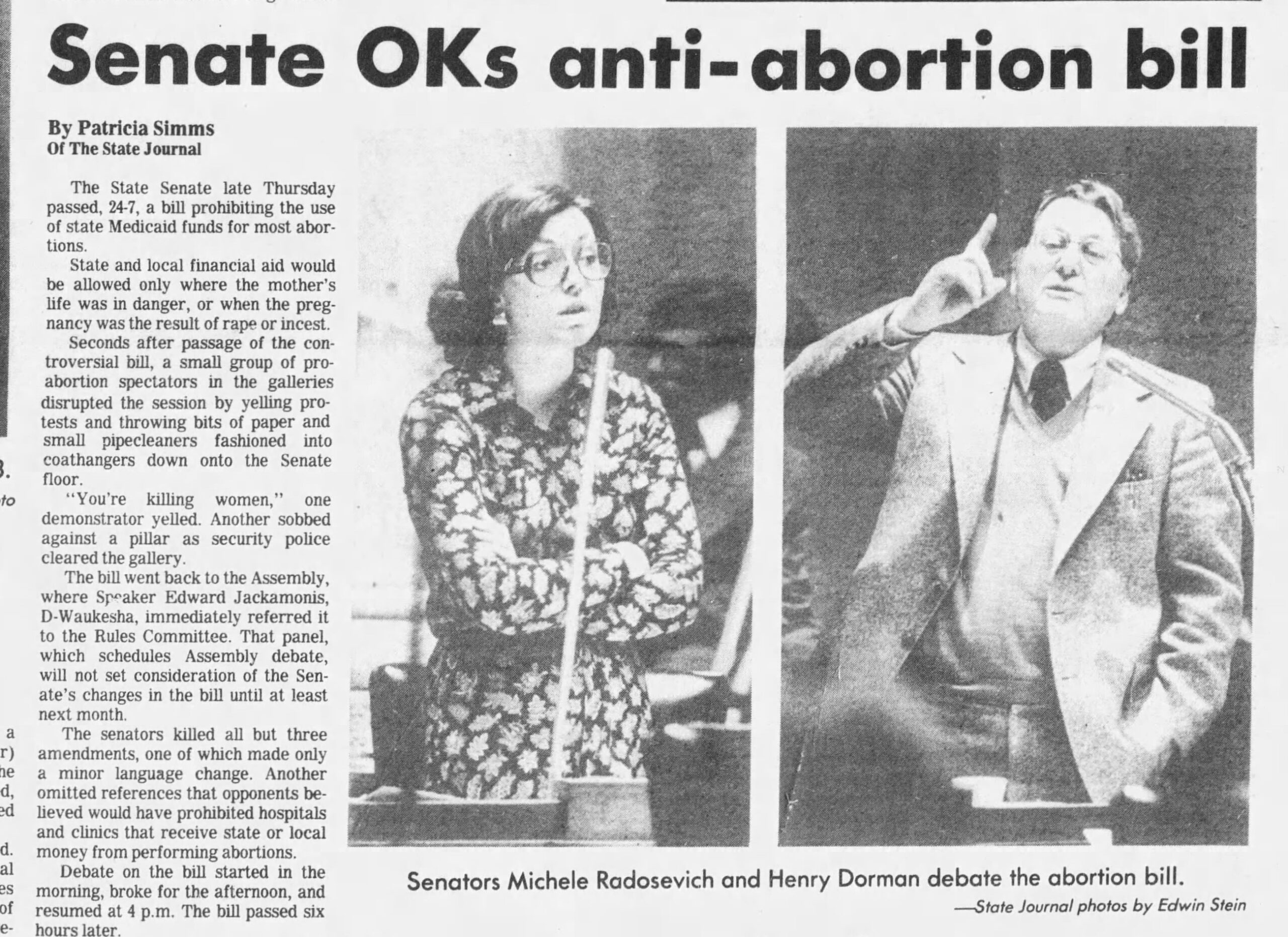

The rhetoric rankled Michele Radosevich, then a freshman Democratic senator from North Hudson. She opposed the bill, which she described as “cruel” because it targeted poor women.

“‘Gentlemen, compassion, please,” Radosevich said at the time. “When you face your God, I wonder what you will tell him.”

The debate lasted days. There were lengthy hearings and dozens of amendments. The bill pinged back and forth between houses before it was finally approved by the Legislature on March 8, 1978.

After all that, Gov. Martin Schreiber, also a Democrat, vetoed the bill the same night.

“I know for sure that a pregnant woman is a human being — a person,” he said when explaining his veto. “I, in my own mind, do not know when a fetus becomes a human being — a person.”

The infighting among Democrats did not end that night. They organized an attempt to override Schreiber’s veto. And they came within two votes of succeeding.

Democrats would have restricted abortion further — if it weren’t for pro-choice Republicans

At this moment in time, the parties were split on abortion throughout the country, said Mary Ziegler, a leading expert on the history of abortion in the post-Roe v. Wade era.

“In the ’70s, the parties didn’t have clear identities yet entirely when it came to abortion,” she said. “The idea that the Republican Party was the party of life, as Ronald Reagan put it, or the anti-abortion party, and the Democrats were supportive of legal abortion wouldn’t really coalesce until the early ’80s.”

That divide played out in the 1978 debate on abortion. Rep. Sheehan Donoghue, a Republican, was instrumental in defeating the bill, not only voting to uphold Schreiber’s veto but also delivering an impassioned speech that at least one lawmaker credited with changing his mind.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Donoghue told her colleagues, “What you do here today, you will have to live with the rest of your lives.”

Today, Donoghue is retired, living in northern Wisconsin. She still remembers the debate and her reasons for opposing the bill.

“This legislation, in my opinion, did damage to the equality of women in control over their own bodies,” she said.

She said she was particularly concerned the bill — while it included exceptions for rape, incest and the life of the mother — did not account for pregnancies that could harm the health of the mother.

“I found a real inconsistency there,” she remembered. “And I thought it was cruel towards women who happened to be on welfare, who had some problem, some physical problem, (if the pregnancy) would incapacitate them but not kill them.”

The veto override failed by two votes, meaning Donoghue and other Republicans who opposed the bill were critical to its defeat.

But it wasn’t a clear-cut victory for abortion rights lawmakers. Days after Schreiber’s veto, the Legislature passed a more limited bill that included protections for the health of a mother. Schreiber — who said he was “personally opposed” to abortion — signed it into law.

As anti-abortion voters organize, the parties split

The bipartisan coalitions that worked for and against the bill would be hard to imagine today, but Radosevich, the Democratic lawmaker who spoke so fervently on the floor, said they were common in the late ’70s.

“It was a very different time in terms of party alignment,” she said.

Still, Radosevich, a freshman lawmaker from a competitive district, knew the power of the abortion issue with voters. She had originally planned to stay quiet during debate and acknowledge that some of her Democratic colleagues were “just a little bit scared of the voters back home.”

Their silence, and the arguments from anti-abortion lawmakers, propelled her to speak up. That landed her on the front page of the Wisconsin State Journal. She said she thinks that public stance, and the ensuing attention, contributed to her losing her next election.

“But, you know, there’s no way I could have voted for the bill and looked at myself in the mirror the next day,” she said.

On the other side of the abortion debate from Radosevich was Gary Goyke, then a Democratic state senator from Oshkosh. He voted in favor of the bill restricting Medicaid funds, telling WPR he viewed it, at the time, as the government removing itself from the abortion decision.

But Goyke described it as a turning point for him, personally. He said he began to move more toward embracing abortion rights, including in his unsuccessful bid for Congress just a year later.

That personal evolution wasn’t without consequence. Goyke, a Catholic, remembers being confronted at church.

“A lady would come sit right in the front row. And at every service that I was at — every Mass I was at — she would stand up and say, ‘Let us pray that Sen. Goyke learns to respect life,’” he remembered. “And then the parish would say, ‘Lord, hear our prayer.’ And I am sitting right in front.”

It was around this time when politically active anti-abortion voters were becoming a force in the Republican Party. But it didn’t happen overnight.

When Barbara Lorman was first elected as a Republican state senator in 1980, she openly supported abortion access.

“I think I’ve always been pro-choice,” Lorman told WPR. “And it’s probably also what led me to be a Republican.”

Lorman said she always viewed her position on abortion as consistent with traditional Republican values, like minimizing government control over peoples’ lives. At the time, she says none of her Senate colleagues objected.

“You know, almost anybody could fit in either party, frankly,” Lorman said.

But by 1994, it was a different story. After the 1990 Census, Republicans redrew her district, making it a lot more conservative — a safe seat for the GOP.

She drew a primary challenge from Scott Fitzgerald — whom she describes as a “darling of the right wing” — and says anti-abortion activists threw their weight behind him immediately.

“Those are very devoted, conscientious voters. And like overnight, yard signs went up and down the highway,” she said. “And I saw that and I thought, ‘Uh oh, this is gonna be a problem.’”

Fitzgerald won and went on to serve in the Senate for decades. He’d later become the Senate’s Majority Leader and now represents the area in Congress.

The win was more than symbolic. In 1997, Fitzgerald was the lead sponsor of a law that banned “partial birth abortion” in Wisconsin, one of several incremental abortion restrictions championed by the anti-abortion movement in the decades since Roe.

Democrats undergo their own shift, but slowly

Democrats were undergoing their own shift toward abortion rights politics. In the 1990 race for attorney general, for example, the Republican incumbent signed on to a legal brief that supported overturning Roe v. Wade. His Democratic challenger, Jim Doyle, used it to campaign against him.

“That was the number one issue,” Doyle said. “That’s how I got elected. So it really was … always a very important issue to me.”

Doyle later became governor and in 2009, Democrats won majorities in the Senate and Assembly. The party once again had complete control over state government for the first time in decades.

Among the Democrats swept into office was Kelda Roys, a Madison state representative who, at 29, was the youngest member of the Legislature. Roys won a Democratic primary for her seat, in part, by touting her work as a lobbyist for NARAL Pro-Choice, an abortion rights group.

“I came in just full of energy and optimism,” Roys said. “Like, ‘Let’s do all the things.’”

One of her most ambitious goals: To overturn the dormant pre-Civil War abortion ban she knew was still on the books.

There were two problems, as Roys remembers. She said some abortion rights Democrats took Roe v. Wade for granted as settled law. And while Democrats held a slim overall majority, when it came to the issue of abortion, they didn’t really have one at all. A handful of Democrats were still staunchly anti-abortion.

“It seemed like something that was symbolic,” she said of taking on the dormant law. “And so there just wasn’t necessarily the big appetite to do it. And we didn’t have the votes in that particular session, because we had all these anti-choice folks in our caucus.”

Bob Ziegelbauer was one of the Legislature’s remaining anti-abortion Democrats. Now the Manitowoc County Executive, he says his stance on the issue was clear to everyone in the Democratic caucus. He doesn’t remember ever being approached about working to lift the abortion ban.

“They wouldn’t even think of asking me that, because it was so clear,” he said. “It didn’t come up, because they knew me and I knew them.”

The cordial relationship came to an end during a debate on the 2009 state budget. Ziegelbauer supported a Republican amendment to restrict abortion, infuriating Democratic leadership. In response, they stripped him of a committee chairmanship. Later, Ziegelbauer left the party.

“That was the only time I crossed that line. And that line is pretty bright,” Ziegelbauer said. “They don’t want you doing that.“

The 2009 session of the Legislature was defined by a difficult state budget and debates on issues ranging from payday loans to global warming to raw milk. Discussions of Wisconsin’s pre-Civil War abortion ban never surfaced publicly.

The ironic twist to Democrats’ new fight

The Democratic majority of 2009 was short-lived. In 2010, a Republican wave election gave the GOP control of the Legislature and brought Scott Walker into the governor’s office.

That Republican coalition was much more willing to use its power to effect abortion law. In just a few years, they passed laws ending state funding for Planned Parenthood, requiring patients seeking an abortion to view an ultrasound first and banning abortion after 20 weeks.

Anti-abortion victories around the country culminated in 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. For the abortion rights Democratic Party, it was the worst case scenario — something advocates like Roys had warned could happen.

Strictly politically speaking, however, that moment had a galvanizing effect for Wisconsin Democrats. Last fall, Democratic Gov.Tony Evers, who was viewed as vulnerable in his bid for reelection, ran hard on the issue of abortion — and won.

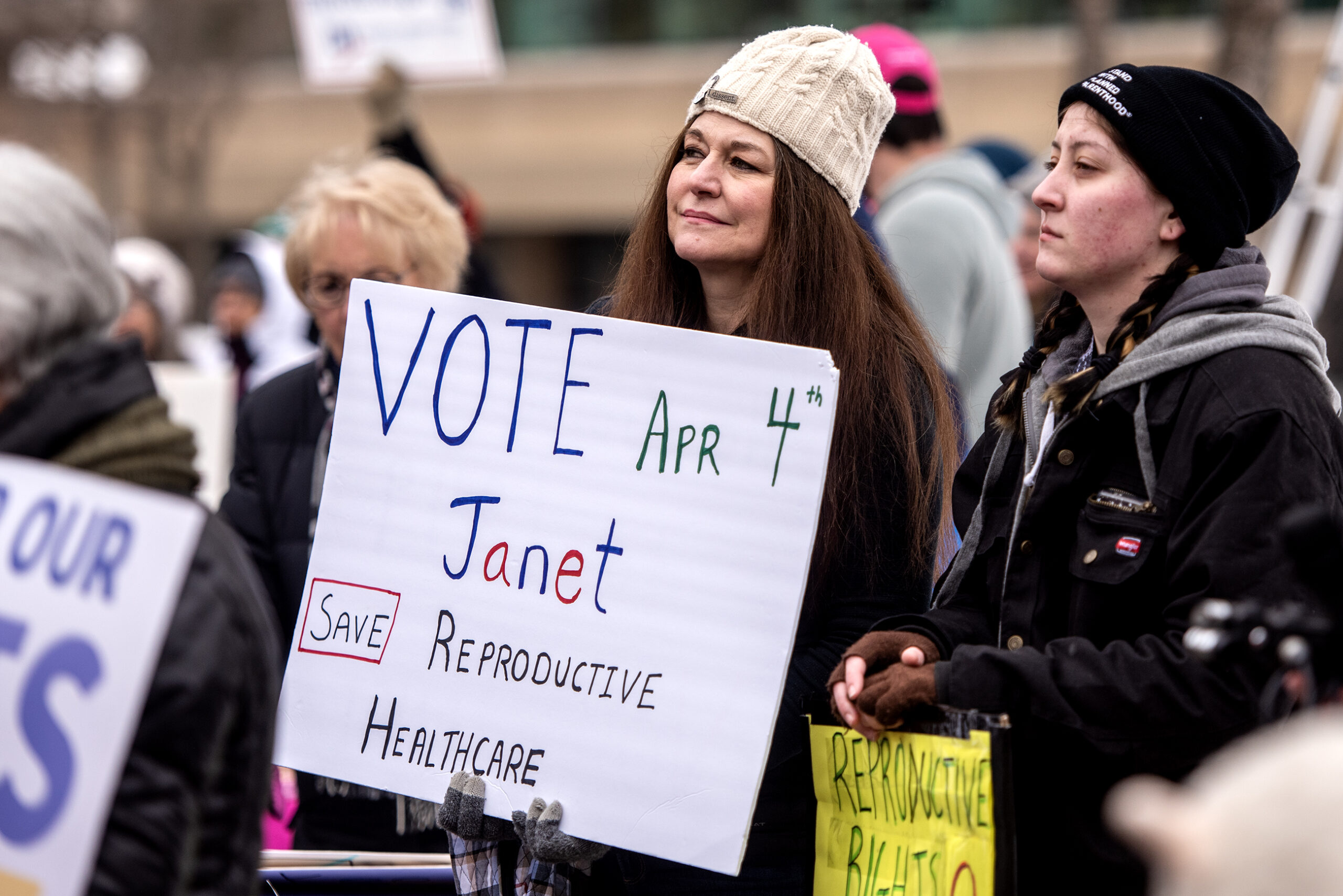

This spring, Justice Janet Protasiewicz likewise placed abortion rights front and center in her campaign for state Supreme Court. That proved a winning strategy for her campaign, too.

When Protasiewicz was sworn in earlier this month, liberals gained a majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court for the first time in 15 years. That state Supreme Court could have the final say on any challenges to Wisconsin’s abortion laws. If a pending lawsuit succeeds, the abortion ban could be gone.

Today’s Democratic Party is pushing hard for this. The state party poured millions of dollars into Protasiewicz’s campaign, and earlier this year, every single Democratic member of the Legislature supported a proposal to overturn the state’s abortion ban.

If the ban is overturned, abortion would once again be legal in Wisconsin, but the laws that were passed in the years after Roe would also be restored.

That means decades’ worth of abortion restrictions would again be the law of the land — from the Medicaid restrictions passed in 1978, to the 20-week abortion ban signed by Walker in 2015.

With the parties now firmly entrenched on this issue, the fight over abortion in post-Roe Wisconsin would go on.

For more from “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” visit wpr.org/1849.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.