Testing to detect lead poisoning among kids in Wisconsin declined substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic. While more children are getting tested, around 17 percent fewer kids were screened last year compared to 2019.

In 2019, around 83,000 kids in Wisconsin under the age of six received blood lead testing. That dropped by roughly 22 percent to 65,000 kids in 2020. Last year, around 69,000 kids received testing statewide, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. That’s still well below pre-pandemic levels.

“Part of the decline has been just kids getting back into their providers’ office for well-child checks,” Kim Schneider, a public health nurse for DHS, said. “That has continued to be decreased since the pandemic.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

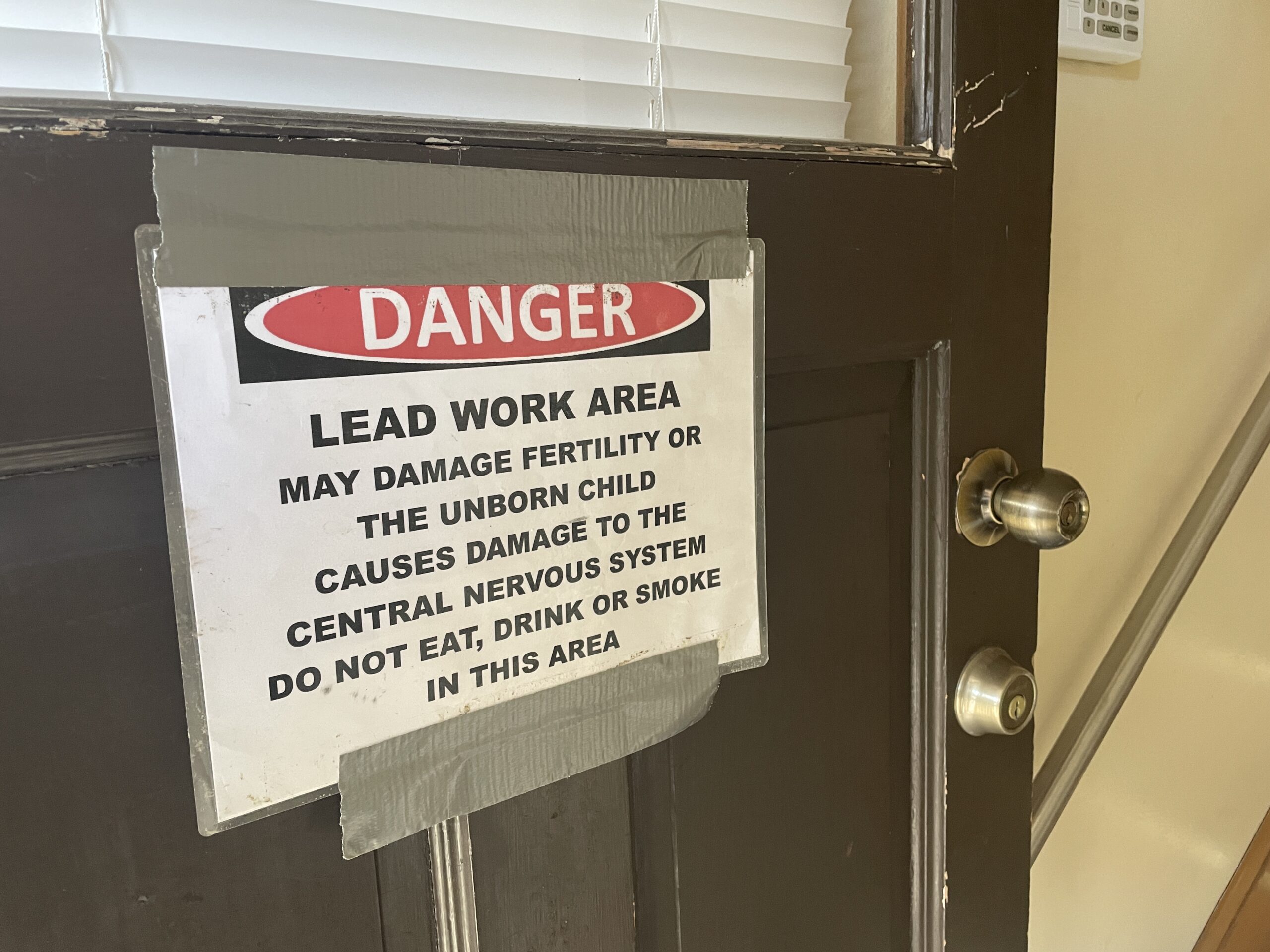

There is no safe level of lead exposure. Lead exposure can cause damage to the brain along with learning and behavioral problems in children. Kids are at higher risk of lead poisoning if their families live in older homes with deteriorating lead paint, which is the primary source of lead exposure in Wisconsin. They can also be exposed by lead-tainted dust, soil and water.

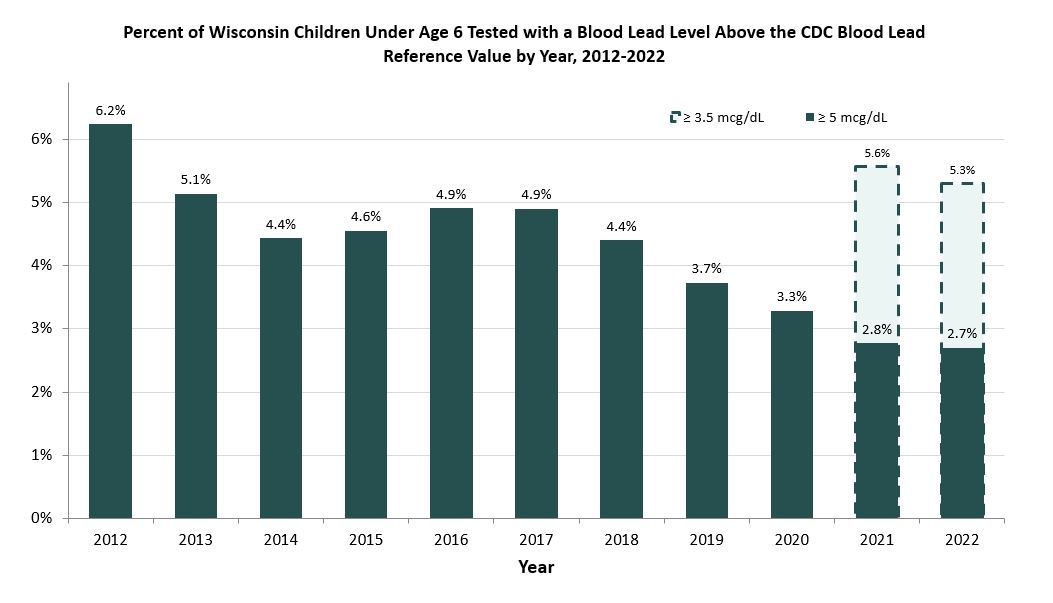

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, had been using a reference value of 5 micrograms per deciliter to identify kids with higher levels of lead in their blood, which is the state’s definition of lead poisoning. The number of children with high lead levels in Wisconsin had been largely declining since 2012. However, the CDC lowered that threshold to 3.5 micrograms per deciliter in 2019. Since then, the change means the number of kids considered lead poisoned by state health officials has doubled.

Last year, figures provided by DHS show 3,679 children or 5.3 percent of around 69,000 tested statewide had a blood lead level greater than 3.5 micrograms per deciliter. That compares to 1,878 kids or 2.7 percent of children tested under the old threshold.

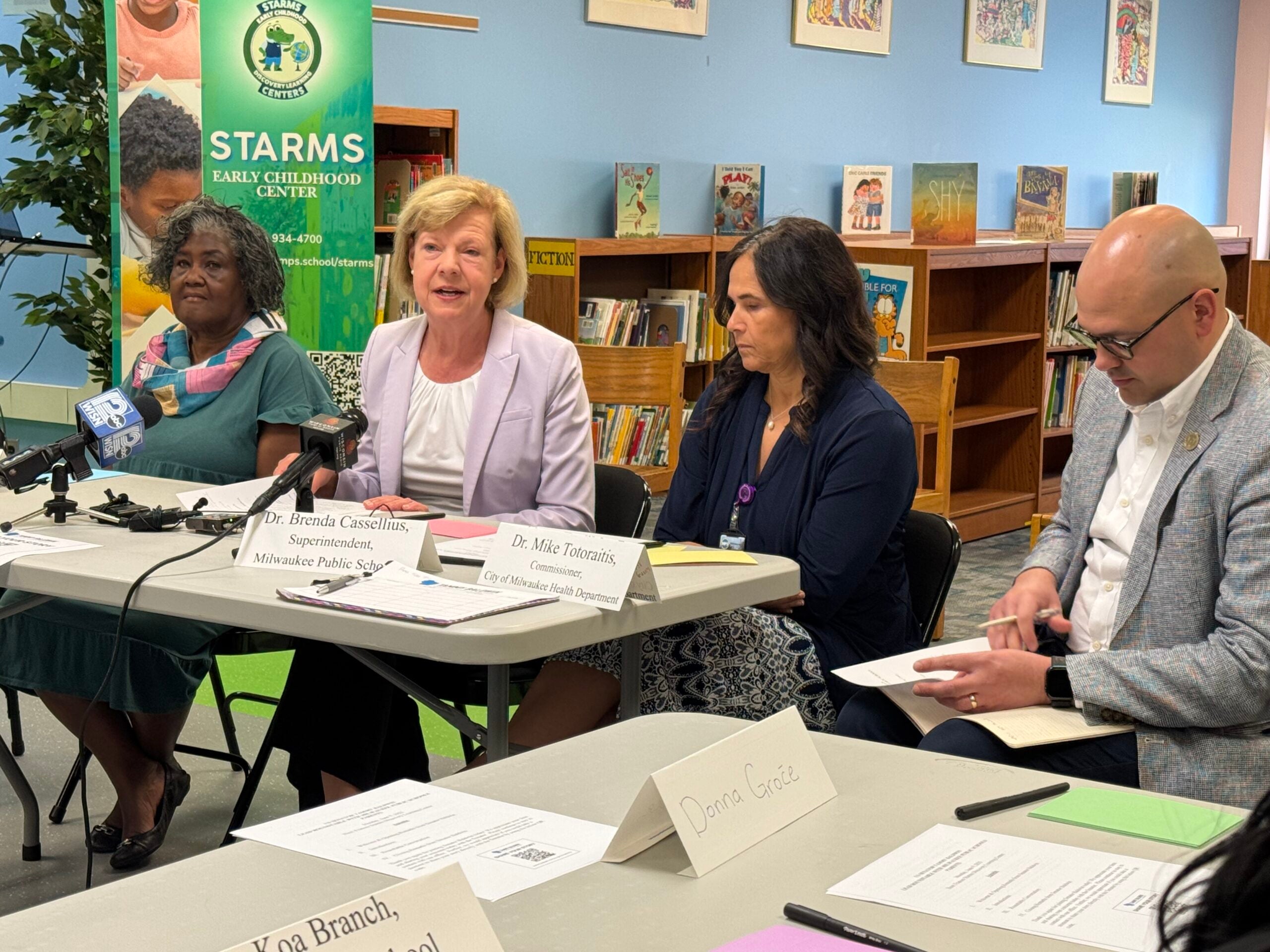

Schneider said Milwaukee and Racine were among communities with the highest prevalence of lead poisoning based on the CDC’s reference value.

DHS figures show Milwaukee accounted for more than half of all kids statewide that had lead poisoning. The city had 2,032 kids that tested at or above the CDC’s value, according to city health officials. That’s 10 percent of all children tested in Milwaukee last year. About 8 percent of children tested in Racine or 116 kids had lead poisoning.

The state recommends testing children in those cities three times before they turn three years old because of the older housing stock. It’s also suggested they test at-risk kids once each year between the ages of three and five, or if they’ve never been tested.

Michael Mannan, director of Home Environmental Health with the Milwaukee Health Department, said the city has faced lower levels of screening after the COVID-19 pandemic halted testing at some clinics.

“And a lot of parents didn’t take their children back to their primary care physicians,” Mannan said.

Mannan noted parents often face barriers with transportation to access health care. Holly Nannis is a public health nurse supervisor with Milwaukee’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program. Prior to the pandemic, she said almost 40 percent of kids tested received screenings from the state’s Women, Infants and Children offices, which weren’t open to in-person services during the public health crisis. For families that don’t have a physician, she said they’re taking steps to help assign them a provider.

At the same time, the Milwaukee Health Department has been working to restore trust after the department failed to follow up and provide services to families of kids that had elevated lead levels in 2018. Since then, the health department has seen a change in leadership. An audit released last year by the Public Health Foundation found the department’s lead prevention program has improved case follow-up, documentation and response time.

Moving forward, Nannis said they’re collaborating with Children’s Wisconsin and other organizations on community screening to increase testing, including the Coalition on Lead Emergency in Milwaukee. Shyquetta McElroy, the group’s director of community organizing, said the lack of testing is a huge problem in the city.

“Families don’t know that their pediatrician or their family doctor is supposed to be testing their children,” McElroy said. “And a lot of doctors don’t tell families that they should be testing their children.”

She’s been conducting outreach on safe drinking water and lead hazards in the home, giving out hundreds of lead-safe kits and water pitchers. The issue is personal for McElroy whose teenage son had blood lead levels ranging from 5.5 to 9.9 micrograms per deciliter.

“These children have to live with the effects of being lead poisoned for the rest of their lives, and my son is one of those children who now have cognitive educational delays,” McElroy said.

McElroy said the city’s low-income neighborhoods are often the most affected by lead poisoning. A 2020 study by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee examined 215 census tracts in Milwaukee County and found lead poisoning predominantly in high poverty and majority non-white areas. Now, McElroy said she’s doing everything she can to ensure another family won’t have to go through the struggles that she and her son have faced.

The state is also working with the biotechnology company Novir to increase testing. Peter Klug, the company’s vice president of business and program development, said the company began doing lead testing six months ago.

So far, they’ve conducted a dozen events at schools in the region like Next Door, which provides early childhood education in Milwaukee. He said they’ve tested more than 200 kids, adding around 9.9 percent exceed the CDC’s value for lead poisoning.

“If it’s difficult for parents or families to get their kids to a pediatrician, let’s bring the services to the school where they go every day,” Klug said.

As local and state health officials strive to increase testing, Gov. Tony Evers’ budget seeks to align Wisconsin’s definition of lead poisoning with the CDC threshold. He’s also proposing more than $300 million to combat lead poisoning.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.