Republicans have removed a key sticking point in a robust bill that revamps how children learn to read, but the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction says the changes aren’t enough to gain their support of the legislation.

The legislation introduced last week included a requirement beginning Jan. 1, 2025 that third graders who can’t pass a reading assessment be held back rather than moving on to fourth grade.

DPI said they were blindsided by the requirement and called the provision a “non-starter.” This led Republicans to amend the bill by changing the retainment policy to requiring the student to repeat third grade reading, not the entire grade.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But during a Senate Committee on Education hearing Thursday, DPI representatives said holding third graders back for one subject is still retention.

“Simply retaining a student in third grade reading is still a retention policy and that is not something DPI can support,” said Laura Adams, policy initiatives advisor with DPI. “We know that there is a great deal of research that show there is mixed results at best for any type of retention for students.”

State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R-Sturgeon Bay, one of the authors of the bill, said he wishes the word “retention” was never used in the bill because of the negative connotations.

“I think it’s that word that freaks people out,” Kitchens said. “Third grade retention is not grade retention. It’s a delicate balance getting all the parties happy, but third grade retention in reading is just not a big deal.”

Kitchens said school districts will have four years to decide how third graders will be screened and what screening tool will be used.

“All of the kids who will be subject to that will be identified in kindergarten and first grade and be going through the whole process, so I imagine (problems) being identified right away,” Kitchens said.

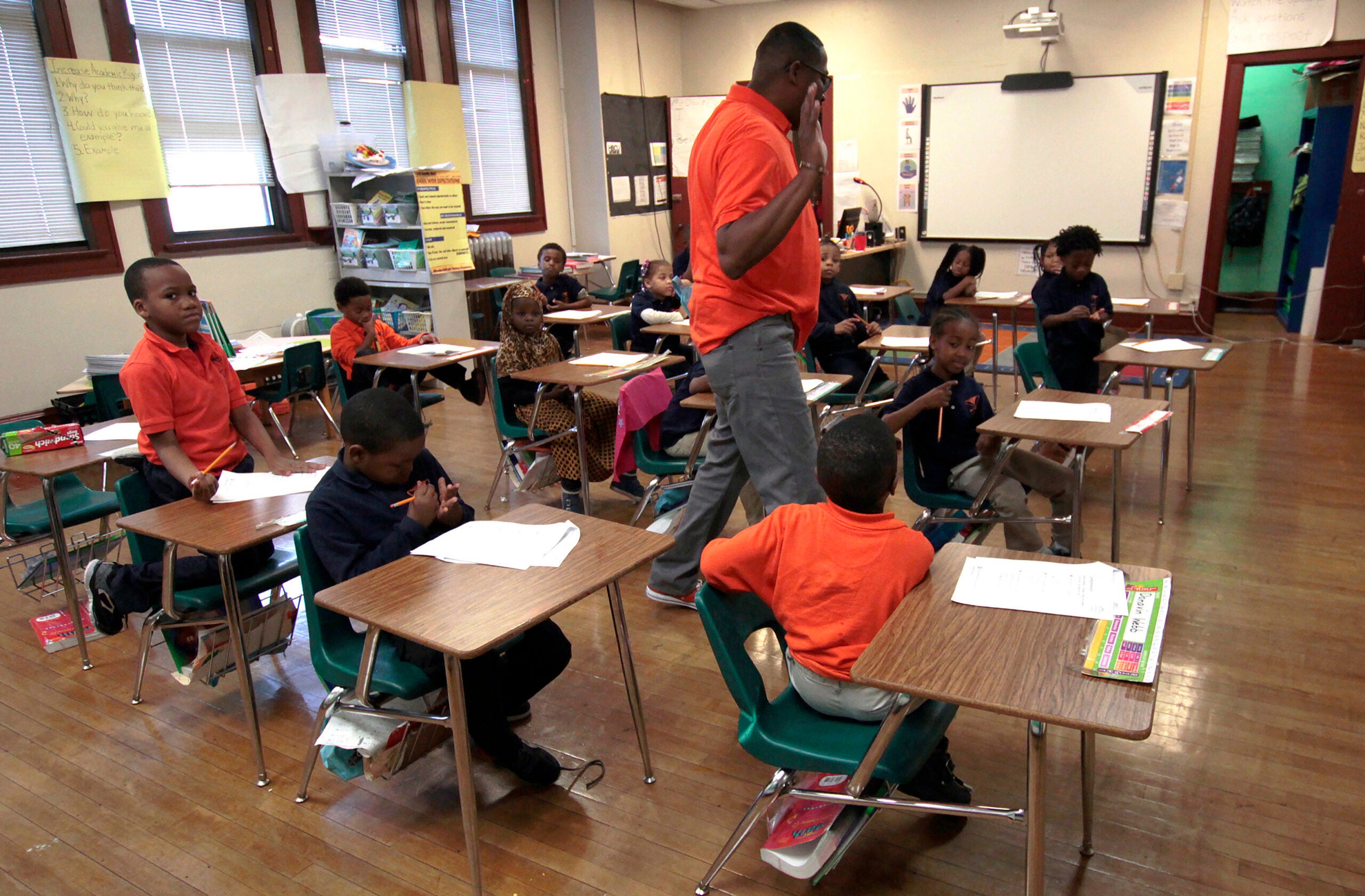

The heart of the bill moves schools away from teaching what is known as “balanced literacy” to a “science of reading” approach. Instead of being taught reading through pictures, word cues and memorization, children would be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on learning to sound out letters and phrases.

Adams said DPI supports that approach as well as other aspects of the legislation, including the development of individualized reading plans, diagnostic screenings for students and coaches in schools.

The $50 million bill includes 64 reading coaches who would be divided between low-performing schools and other school districts that want to apply for help.

Tom McCarthy, executive director of the office of the state superintendent, said there are more technical things that need to be done to get the bill through.

One area of concern is how students who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind and visually impaired, or have an individualized education program will be screened.

“This is a generational change piece of legislation and if we get them right, it will set our state going in the right direction. But change is challenging, and it requires people to take time, think about things and prepare them for that change, otherwise we’re all going to be stuck looking like anchors in the sand,” McCarthy said.

State Sen. Chris Larson, D-Milwaukee, pushed back on several aspects of the bill, including third grade retention, the narrow focus on reading rather than all subjects and the limited number of reading coaches.

Larson said he reached out to all Wisconsin school districts to ask what they think of the reading bill and heard back from 32 superintendents. Of the respondents, 30 said they had a problem with the idea of more testing, mandates and retention, Larson said.

New Berlin Superintendent Joe Garza was not one of them. Garza testified Thursday, saying for eight years his district taught balanced literacy, spending millions of dollars on curriculum and teacher training only to see reading and English scores not where he wanted them to be.

The New Berlin School District has 4,200 students in suburban Milwaukee and is one of 13 districts that ranks as “significantly exceeding expectations” on the DPI state report card.

Garza said three years ago, he started digging deeper into reading research and realized he made a horrible mistake in choosing balanced literacy.

“Teachers did not cause this. I messed up,” Garza said. “I recommended the wrong thing eight years ago, and we were struggling.”

Since changing to the science of literacy approach, reading scores for kindergarten through third graders have gone up 5 points. Middle school scores have also increased, Garza said.

“While no bill will ever be perfect, I fully support this because it has checks and balances, it includes appropriate funding and also accountability,” Garza said. “This will move the needle forward on literacy rates in the state of Wisconsin. We are so very close, DPI, Rep. Kitchens and others. Please get us to the finish line.”

Editor’s note: This story’s headline has been updated to reflect the proper name of the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.