Wisconsin researchers are joining a worldwide effort to preserve cures for common infections by using crowdsourcing to discover new antibiotics.

A dwindling supply of new antibiotics is a health threat that scientists around the world are trying to solve, and in this country, experts say the problem is compounded by a shortage of science graduates.

“If we could get every freshman in college, not just the STEM ones but everybody, into research courses and teach them the excitement of discovery and what science really is — the inquiry process — and hook them on it, we would have … a chance of keeping more students in science — since 60 percent of them leave — and even better, we could have a scientifically literate society,” said Jo Handelsman, director of Wisconsin Institute for Discovery Director as she spoke to instructors from eight University of Wisconsin System schools and more than a dozen other colleges and universities during a recent science seminar.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The educators came to UW-Madison in early January to take a week-long crash course as part of what’s called the Small World Initiative, a program Handelsman started in 2012 to discover new antibiotics and keep students interested in science. Instructors learn how to teach their students how to look for new antibiotics to replace those that no longer work.

UW-Green Bay associate professor Brian Merkel. Shamane Mills/WPR

“Once I heard about it, I just couldn’t believe something like this existed,” said Brian Merkel, an associate professor at UW-Green Bay. “So for me personally, professionally I’m going to learn some new things which I’m very excited about, very passionate about, but I think what it can do for our students and how it can address this problem — do all at the same time — it’s an incredible opportunity.”

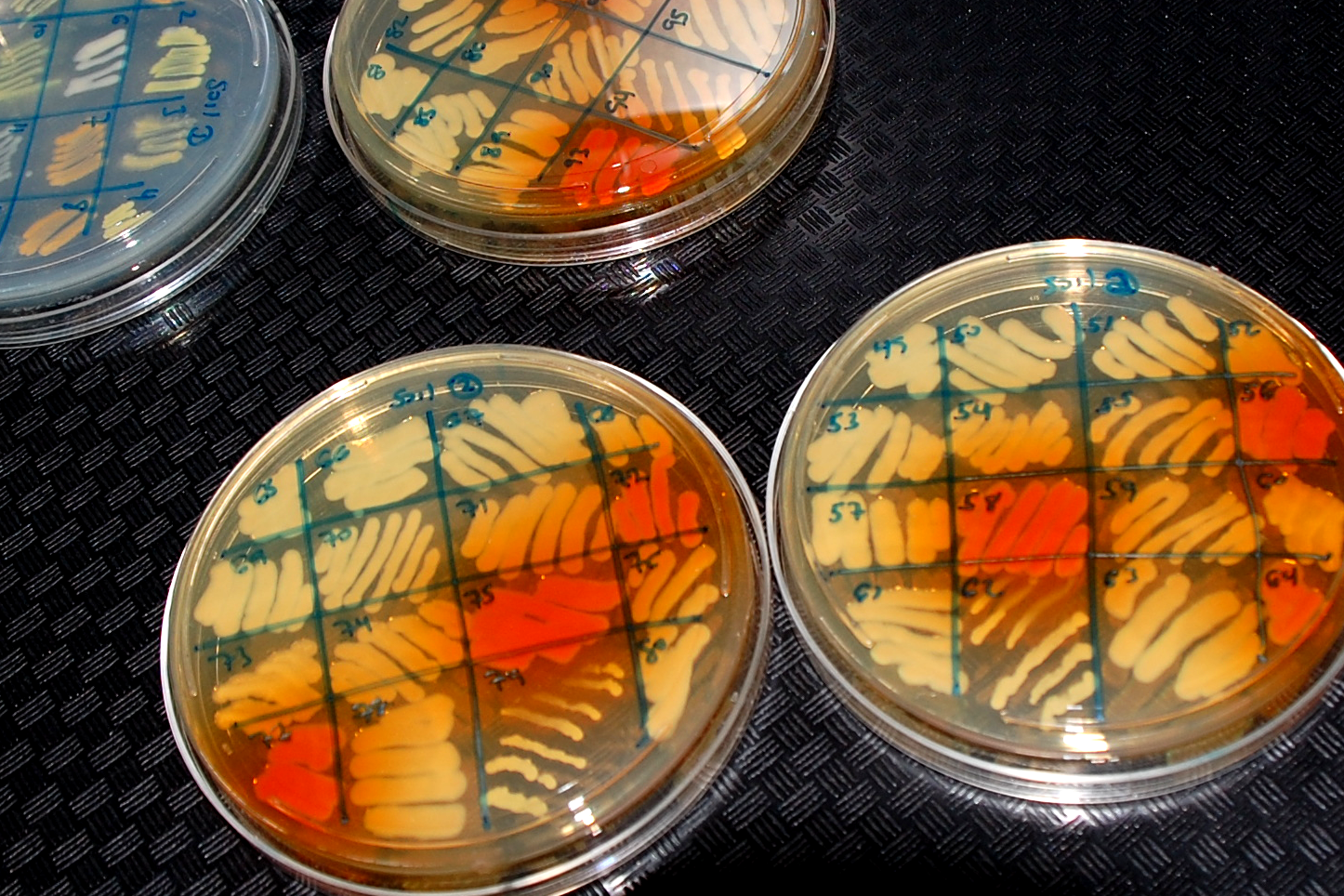

In addition to classroom time, participants took part in lab research, testing soil samples for bacteria that could fight germs. Many of the most widely used antibiotics have come out of the dirt and that’s where those in the Small World Initiative look.

“Those of you who came from (Wisconsin) you are charged with bringing your own soil sample. I think I saw some baggies. And so those you who didn’t we have some soil samples for you,” University of Connecticut biology professor Nicole Broderick told the group of white-coated student-teachers assembled in one of the WID labs. Broderick temporarily ran the Small World Initiative when Handelsman served as President Barack Obama’s science advisor, and she continues to help as an instructor.

Small World Initiative participants test soil samples in Madison. Shamane Mills/WPR

The educators in the Madison course are acutely aware of the magnitude of their mission. If new antibiotics aren’t found, the world could return to a time when simple infections were fatal. Merkel, the UW-Green Bay professor, understands this both on a scientific and a personal level. When he was 18 years old, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia and had a successful bone marrow transplant. His operation underscores the importance of having antibiotics to fight bacteria when one’s immune system is compromised. But he said its bigger than that.

“The reality is now it’s not just that you have to go through a serious health crisis. There can be infections that were considered at one time minor, that become a crisis for certain individuals. So we all have a vested interest in this,” Merkel said.

A couple of trends contributed to what experts say is a public health crisis. In the 1980’s many big pharmaceutical companies stopped making antibiotics in favor of making more lucrative drugs. As the production of new antibiotics has decreased, there was also an increase in superbugs that were resistant to existing antibiotics.

Medical scientists and researchers around the world say too many patients are getting antibiotics when they shouldn’t.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been trying to educate people about inappropriate use of antibiotics, which only work on bacteria, not viruses. And there’s been an effort to reduce antibiotics used in farm animals raised for meat. Some hospitals in Wisconsin are now using antibiotic-free meat.

Other ways health systems are trying to prevent superbugs are by taking out catheters faster and working with the academic and private sectors to develop new medical tools for inhibiting antibiotic resistance.

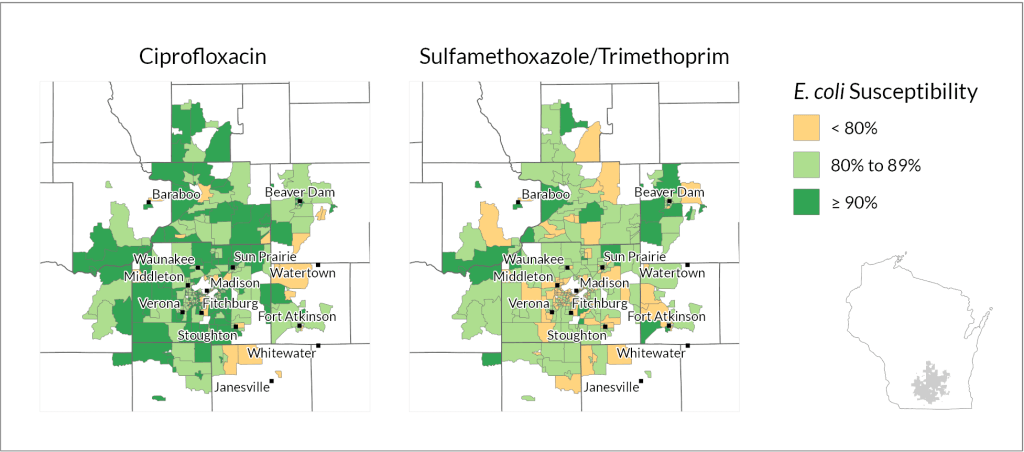

The CDC is also helping states improve their detection of pathogens. The agency’s newly released antibiotic resistance map provides details on superbug cases and efforts to contain their spread.

Since bacteria will continue to evolve, the best health officials can do is slow down the rise of superbugs as they try to speed up the effort to find new antibiotics to kill resistant germs.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.