When Dianna Wells found out she was pregnant in 2018, she did what most parents do: She started searching for reliable child care.

And then she heard horror stories about potential providers in the Madison area being understaffed or unexpectedly shutting down.

“And the cost!” Wells said. “The cost was incredible.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Wells’ journey to find safe, accessible and affordable child care wasn’t easy. She even had to cut back her hours as a teacher in the Verona Area School District to make it work.

Her experience is far from unique as Wisconsin, like the rest of the nation, faces a shortage of child care workers.

Over half of Wisconsin is in a child care desert, meaning for every open child care slot available in a community, there are three or more children who need it, according to a report by the Wisconsin Early Childhood Association.

In Wisconsin, 288,430 children have a potential need for child care. There are 171,040 slots, according to the same report.

At the same time, child care isn’t affordable. The average two-income household is spending 17 percent of their income on child care for one child. That’s more than what most people are paying for their children to go to college, according to a report from Child Care Aware of America.

For the last three years, Wisconsin child care providers have been buoyed by a federal pandemic relief program that helped them improve pay for their employees while keeping tuition costs for families down.

In June, funding for that program, called Child Care Counts, will be cut in half and new restrictions will be put into place. Democratic Gov. Tony Evers included $340 million in his 2023-25 Wisconsin state budget to stabilize the program.

As the budget makes its way through the Republican-controlled Legislature, so far that funding remains in the budget. But it’s seen as at risk, and preserving the funding is the subject of a statewide letter-writing campaign among child care professionals and advocates.

The shortages in Wisconsin of affordable child care options predate this budget battle, and no one thinks this year’s state budget will solve them. That often leaves parents with impossible decisions.

When Wells needed to find care, she contacted her sister-in-law, Corrine Hendrickson, owner of Corrine’s Little Explorers in New Glarus, but there was a yearlong waiting list. The center is also an hour’s drive from Wells’ home in Verona.

Left without a choice, Wells waited. In the meantime, her mother-in-law moved in to help with child care.

Now her son, Kai, 4, and daughter, Quinn, 3, are at Corrine’s Little Explorers. Her children are thriving, but Wells, who teaches Spanish, had to cut her hours 20 percent.

“Two hours of my day is spent in the car when I can’t be prepping for my lessons, I can’t be grading,” Wells said.

Child care gaps are a problem in Wisconsin’s economy

Corrine’s Little Explorers was born out of an urgent need for child care in Green County. Twenty-five years ago, there were 90 child care providers in Green County. Today, there are 29.

Corrine Hendrickson’s child was 10 months old, and she was working in retail 15 years ago when she decided to open her center. Three of her friends were pregnant at the time, and they were frantically trying to find open child care slots.

Today, Hendrickson’s waiting list is long, with many parents willing to drive to her New Glarus home from Dane County. Hendrickson is not surprised. Her rates range from $180 to $210 a week, about half the price of centers in Verona and Madison, she said.

“I could have raised my rates, and I could charge a lot more, but I don’t want to be a program just for those who can afford me,” Hendrickson said.

Hendrickson has become an advocate with other providers and parents trying to solve Wisconsin’s child care crisis.

Even as the cost of child care has risen, child care providers themselves often struggle to earn a living wage. The average pay for the profession is between $7 and $12 an hour, making it one of the lowest-paid in the state, Hendrickson said.

Charging more is impossible, because it would put families at a total economic disadvantage.

If a child spends eight hours a day in child care, five days a week, a family is spending $280 a week or $1,120 a month if they are paying their provider $7 per hour. If the cost is $12 an hour, their cost is $1,920 a month — for one child.

“It’s so frustrating that this career is so undervalued and underrepresented and under-voiced in society as a whole,” said Casey Umhoefer, of New Glarus, who spent four years in the profession before the pandemic closed her center. Umhoefer took a job with the state and now says the income difference is so staggering she can’t go back to the career she once loved.

Data published by the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families show the Child Care Counts program has been a success. Through Feb. 18, 2021, 4,892 participating child care providers across the state had received an average of $116,816 each.

An October 2022 survey of Wisconsin providers by the National Association for the Education of Young Children found that 27.1 percent of providers surveyed would have closed had they not received federal funding through the Child Care Counts programs. And a majority surveyed, 60.6 percent, reported that they will have to increase tuition when the program expires.

Shawn Phetteplace, the Midwest manager for Main Street Alliance, a liberal trade group for small businesses, said the future of Child Care Counts affects everyone.

“If we don’t get at least a good amount of funding to that program, I think you’re going to see mass exodus of staff, and you’re also going to see huge rate increases for parents too,” Phetteplace said. “And I don’t think that it’s fully appreciated yet just how fully devastating this would be.”

Raising awareness for a decades long problem

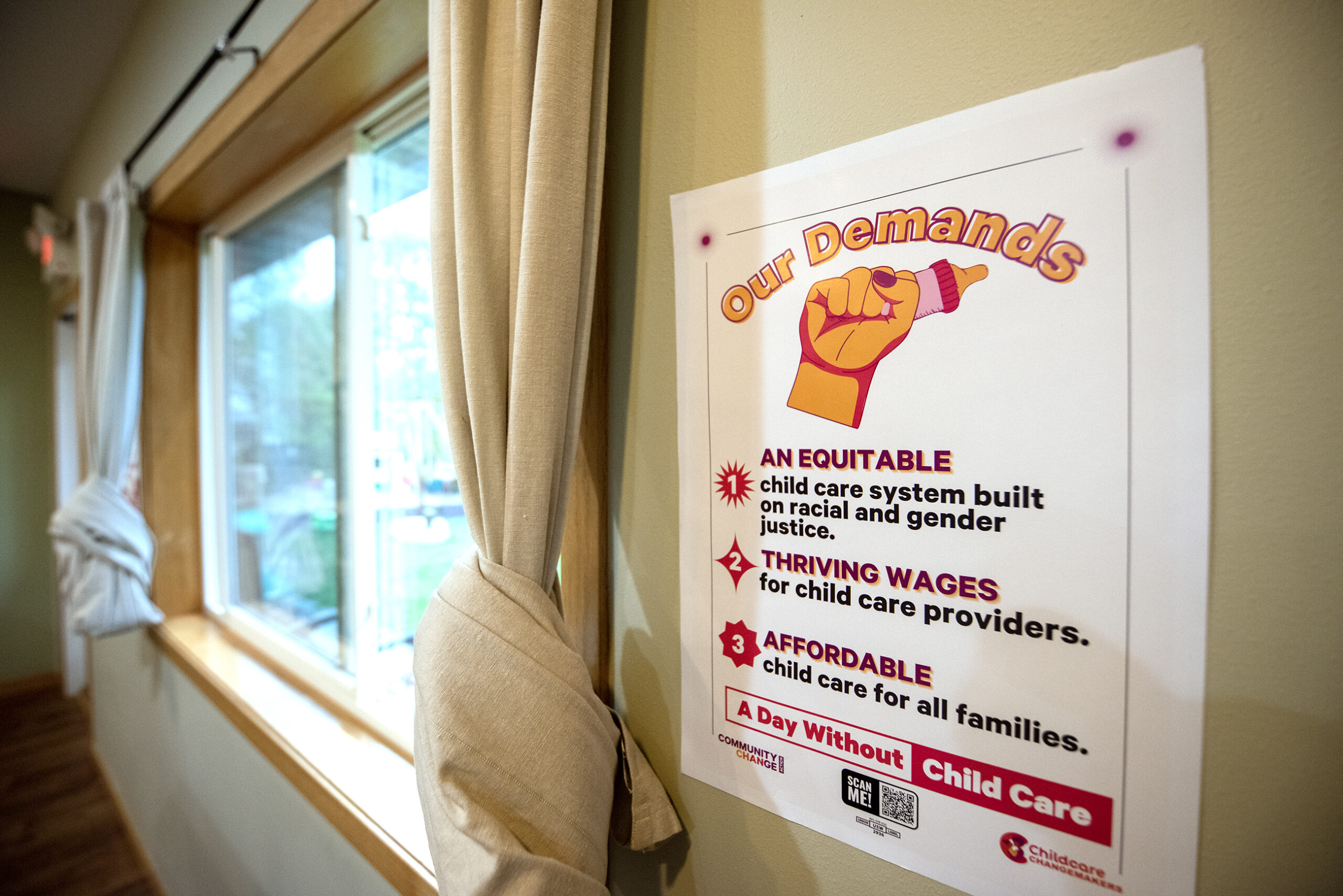

On May 8, child care providers around the country held a “Day Without Child Care” to raise awareness of how financially difficult it is to provide quality care and pay workers a livable wage. Hendrickson hosted the event at The Growing Tree child care center in New Glarus.

With children playing on the floor in one of the Growing Tree classrooms, dozens of parents and providers told emotional stories about trying to find adequate child care providers or trying to make a living taking care of kids.

Wanda Legler, 70, has spent her career in the child care industry. She says it suits her. But it has been a struggle and at this point she’s fed up that the federal and state governments haven’t done more to improve wages.

“A lot of these people making the decisions, honestly feel we (mothers) should just be home taking care of our kids,” Legler said. “And I’ve seen it, I’ve bumped into it, over and over and over again.”

After several hours, A Day Without Childcare wrapped up with parents feeling grateful and providers hopeful.

And right now, Wells, the Verona teacher, has figured out what works best for her family. But she’s already starting to worry about next year, when Kai starts kindergarten in Verona and Quinn is an hour away at a New Glarus day care.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.